Article of the Month - June 2022

|

How to Conceptualize a PPP for Land

Administration Services: Understanding the Private Sector and Commercial

Feasibility.

Tony BURNS, Australia; Fletcher WRIGHT, United

States; Kate FAIRLIE and Kate RICKERSEY, Australia

|

|

|

|

| Tony Burns |

Fletcher Wright |

Kate Fairlie |

Kate Rickersey |

This article in .pdf-format

(18 pages)

This paper uses the experience from drafting the

Costing and Financing Land Administration Systems (CoFLAS) Tool

(UN-HABITAT, 2015), drafting and piloting the Operational Toolkit, and

the Land PPP consultation process (2018-2019), to provide practical

take-aways for governments, development partners and private sector

implementers.

This paper is an updated version of earlier work

published under the 2020 World Bank Annual Land and Poverty Conference

and the 2020 FIG Working Week – both events having been cancelled due to

the COVID-19 pandemic.

SUMMARY

It’s all the buzz, but where do we start? There is a large train

moving that suggests that Land Administration Services can be

transformed by adopting a public-private-partnership (PPP) model, but

when we get into the details, it’s not so clear cut for many

jurisdictions. The underlying principles and precepts applicable to best

practice for PPPs require a deeper understanding of the land

administration context, due to the barriers of implementation in a

developing country.

During reviews and design of Analytical and Operational Frameworks

(World Bank 2020) under the World Bank commissioned Land PPP project,

the team noticed a significant gap between a country’s readiness and

general interest in exploring a PPP approach, and the available data and

preparedness to develop a strong and well conceptualised vision.

Overlooking critical steps in PPP design and implementation, as well

inadequately understanding private sector partner interests and values,

are shortcomings that underpin many of the limited available case

studies.

This paper uses the experience from drafting the Costing and

Financing Land Administration Systems (CoFLAS) Tool (UN-HABITAT, 2015),

drafting and piloting the Operational Toolkit, and the Land PPP

consultation process (2018-2019), to provide practical take-aways for

governments, development partners and private sector implementers. The

experience highlighted how essential the conceptualisation of a Land PPP

is to project validation, risk evaluation and likelihood of success.

The paper looks at the challenges in two ways and aims by the end to

have you answering the question – is your jurisdiction ready? Firstly,

it elaborates the Land PPP Conceptualization Tool, and how it informs

country Land PPP preparedness, flagging necessary steps to address data

needs and gaps. Developed as part of the Public-Private Partnerships in

Land Administration: Analytical and Operational Frameworks (World Bank

2020), it was considered an essential Toolkit component, enabling

development of a clear Land PPP concept attractive to private

investment, and promoting project success through clear metrics and

scoping. This paper reviews the justification, details and enabling

environment for maximum tool effectiveness, through a discussion of the

three steps which guide the project concept development process.

Secondly, the paper emphasizes how parties can work to understand

both government and private sector motivations, approaches, and

attractions at the project conceptualization stage - realizing that an

assessment purely from one angle does not allow for informed decisions

around project feasibility. Fundamentally, a Land PPP requires both

government and private sector willingness and interest to be successful.

1. INTRODUCTION

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have emerged across sectors

including transport, water, waste, and energy – and more recently, PPPs

in the eGovernment sphere have become increasingly common. PPPs in land

administration (henceforth, Land PPPs) have emerged successfully and

less successfully in both developed and developing contexts, and many of

these are examples of e-Government PPPs. Across sectors, successful PPPs

share a set of common underlying guiding principles and precepts. These

principles and precepts, however, require a deeper understanding when

applied to land administration systems. PPPs in land administration are

not new but their application in developing countries raises many

questions about the barriers to implementation.

Existing efforts have largely sought to improve upon existing land

administration systems, but there is a need to further investigate

potential models that will address the registration gap, which currently

stands at approximately 70% in much of the developing world.

During land administration system reviews and design consulting

experiences a noticeable and often unanticipated gap is getting to the

core of land administration systems and practices, particularly in

emerging economies, on matters that are critical to the success of a

potential PPP. A strong project conceptualisation and an understanding

of what motivates the private sector is essential for governments to

successfully design transactions which are attractive to the private

sector.

This paper builds on work undertaken to develop the World Bank report

Public-Private Partnerships in Land Administration: Analytical and

Operational Frameworks (World Bank, 2020) to share some practical

take-aways from the large body of theoretical explanations, targeting an

audience of governments and donors. The paper does this in two ways:

firstly, by exploring key land administration and PPP concepts from a

land administrators’ perspective; and secondly, by examining the

attractiveness of PPPs from a private sector lens, looking at the

overarching perspectives and underlying motivations of all parties.

2. WHAT AND WHY LAND PPP's?

So, what, if anything, makes Land PPPs different? In contrast to

infrastructure or e-governance PPPs, Land PPPs must recognise that land

is a fundamental resource that is managed under typically

long-established policy and legislative frameworks. This ‘stewardship’

must address broad and diverse political, economic, social and

environmental objectives for both the current population and for the

benefit of future generations. Land administration systems (LAS) provide

an important framework that enables governments to address and

understand ‘land’ across these broad objectives. However, whilst there

are generic approaches or methodologies adopted in a land administration

system, such as the options of deed or title registration, there is

great variety in both in how these systems are ultimately implemented in

practice, as well in individual country or region requirements from a

Land PPP. This variation further complicates a standard Land PPP

approach. For example, countries with less well-developed LASs may face

the cost of first establishing a LAS with broad geographic cover and the

records and procedures to support it (“first registration”), in addition

to the direct cost of providing LAS services to those requesting

services. Other countries may seek to digitise hardcopy information or

undertake a process to convert deeds to title systems. These important

contextual factors – and their implications - need to be recognised and

addressed in any attempt to develop a Land PPP concept.

2.1 Potential advantages and drivers of Land

While there are potential complexities of using Land PPPs in land

administration, there are a number of potential advantages:

- The ability to bring private sector capital and finance to

improvements, technology, modernization, and updates,

- The ability to bring outside knowledge and technical skills to

improvements,

- The ability to maximize efficiencies and cost savings through

private sector expertise and management practices,

- The improvement of procedures for setting up land registration

in countries in transition,

- Increased flexibility of land registration services,

- Promoting the use of geospatial base data for additional (e.g.,

private sector) customer groups,

- Improved customer orientation of land administration services.

These potential advantages also highlight that technology is rarely

the sole driver in determining when to implement a Land PPP. Other,

arguably more common drivers include:

- Lack of financial resources for investment in capital

expenditure to replace legacy systems,

- Lack of other resources, such as qualified staff, to implement

legal or procedural change,

- Identified reduction in future operating costs,

- A reduction of the risk in investment, and

- Introduction of process efficiencies delivered via technology.

With the growth of PPP adoption in other sectors, the perceived

attractiveness of PPPs may also be a factor.

2.2 What services can Land PPPs cover?

In developed countries, most projects that have implemented a PPP

model for land administration have focused on two factors: technology

and efficiency. Land PPPs in developing countries may be less

straightforward though, where existing examples have typically required

a combination of building the system, extending the coverage,

computerizing IT and/or rendering the process more efficient. Extending

upon existing examples, there are a range of land administration system

services and activities that a PPP structured financing model could

apply to:

- First registration

- Data digitization and conversion

- Land transactions (including certified extracts)

- Development/building permits

- Registration of professionals (lawyers, surveyors)

- CORS positioning services (main client: surveyors)

- Provision of land valuation information (main client: financial

institutions, real estate brokers, valuers, etc.)

- Land use system, maps, etc.

- Mass appraisal for taxation (main client: central and local

government)

- Preparation of tax rolls and/or tax collection (main client:

central and local government)

- Land use system, maps etc. (main user: local government)

- Bulk transfer of tax records for government use (main client:

central and local governments)

3. HOW LAND PPP CONCEPTUALIZATION INFORMS COUNTRY PREPAREDNESS

Given the range of land administration services and variations

compared to the (relatively limited) range of existing Land PPPs,

developing a clear concept for a Land PPP remains a defining challenge.

The land conceptualization tool was developed as a framework for both

developing a concept as well as validating an existing concept. This

tool is set out in Section 3 of the Operationalization Toolkit, World

Bank (2020). Three key steps for developing a specific concept for a

Land PPP are described below.

3.1 Defining Land Administration Service Modes

The first step is defining the land administration services to be

potentially provided through a Land PPP, and identifying any necessary

changes to the legal, institutional, or operational environments. Land

administration services can typically be delivered in several different

modes or channels. It is important that these different modes are

understood as the current arrangements can impact on a Land PPP concept.

Key factors to be considered include:

i. The services that will be provided through the possible Land PPP

and confirmation that these services can be provided by a PPP operator

under the existing legal framework. ii. The number and location of

offices that currently provide land administration services. iii.

Whether land administration services are provided by isolated offices

that include both front and back offices or the offices supplying

services operate as front-offices with some central office or offices

providing back-office support. iv. The proposed scope of the Land PPP (whole jurisdiction or part

jurisdiction). v. The projected number of transactions and revenue generated based on

decisions made on the services to be provided and the scope of the

proposed Land PPP. vi. The number of staff currently providing land administration services

(employment status, qualifications). vii. The status of the ICT system supporting the provision of land

administration services. viii.The institutional arrangements and mandates for the provision of land

administration services (including consideration of current arrangements

for key services such as ICT, collection and allocation of land-related

fees and charges and the provision of professional services by notaries,

private surveyors and others). ix. Forecast of requirements for investment in first registration, ICT and

other necessary equipment and facilities; and x. A summary of the key rationale for considering a Land PPP (lack of

capital, lack of resources, difficulties with institutional roles and

mandates, etc.).

The Land PPP Conceptualisation Tool (World Bank, 2020) provides an

overview of guiding questions and information necessary to collect to

answer these questions. Entities requiring further support and

structure, to e.g., project revenue and forecast requirements, should

refer to the CoFLAS tool (UN-Habitat, 2015) and supporting Framework for

Costing and Financing Land Administration Services (UN-Habitat, 2018)

for additional guidance and more preliminary tools. As mentioned below

(see Section 4.3 Financing and Payment Approaches to Improve Private

Sector Appetite), there is scope for national (or sub-national)

governments to seek support from development partners to assist with

project conceptualisation (and feasibility assessment, see Section 4).

A key outcome from this analysis should be the identification of any

changes in institutional roles and mandates and in staff employment

arrangements that might be necessary to arrive at a viable Land PPP

concept.

3.2 Defining the

Appropriate Structure for a Land PPP

A second step to developing a Land PPP concept is the consideration as

to which PPP model and structure is most suitable, given the identified

services to be provided and context in which the Land PPP will be

situated. Some of the structures most likely to be applicable to Land

PPPs include joint ventures or concessions. Joint venture structures see

public and private sector partners share revenue, costs and risks, and

for Land PPPs this would likely involve government taking an equity

stake (“shares”) in a project company. In this instance, government has

both a role as a regulator and shareholder in the project company. Joint

ventures could be applicable across the suite of land administration

services, including software development, IT hardware and software

operations, surveying and back office and customer service

responsibilities. Concessions, on the other hand, are a more traditional

model of PPP, typically used in the toll or availability payment

context, whereby a private operator is remunerated on the basis of user

payments or performance measures. Government still maintains a

regulatory role and may need to provide other guarantee or risk

measures. A concession model may be most applicable to contexts of

comprehensive technology upgrading, and/or full commercial operation of

land registries or related functions.

Much has been written on the many PPP structures (and sub-structures) in

practice, and their principal characteristics – more than can be

encompassed in this short paper. Further information to assist in

deciding between and ultimately designing these can be gathered by

referring to commercial contracting information. Broader information is

available from the World Bank PPP Legal Resource Center (e.g.

https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/agreements/joint-ventures-empresas-mixtas,

World Bank 2020) or documents available from the World Bank PPP Library

(e.g. HM Treasury, 2010; PPIRC, 2008; World Bank 1998; EBRD 2008).

Given the relative youth of Land PPPs, governments and practitioners

will likely need to refer to information from related sectors, including

ICT and e-governance.

3.3 A Framework for

Developing the Land PPP Concept

Finally, the third step entails elaborating the Land PPP Concept. This

can be developed by considering the following topics and critical

questioning:

- Project Objective: What issue does the project address? What does the

project aim to achieve? Improved access to services? Reductions in times

taken for processing?

- Targeted Services and/or Functions: What services and/or functions does

the project aim to provide?

- Stakeholders: What stakeholders are involved? Consider the public

sector, the private sector, financiers, operators, and users. What are

their roles and responsibilities in the project?

- Project Demand: Is there a demand for the services or functions offered

by the project? Is the demand sufficient to justify the project?

- Economic Benefits: What are the tangible economic benefits of this

project? Who benefits? Are the potential economic issues posed by the

project implementation?

- Legal and Regulatory Regime: What legal and regulatory regime would

govern the project? Does it adhere to these requirements?

- Capital Investment Costs: What are the estimated capital investment

costs of the project?

- Operating Costs: What are the estimated annual operating costs for the

project? This would include the running of facilities, staff, and other

such costs.

- Revenue Estimates: What is the estimated annual revenue of the project?

- Environmental and Social Impact: What is the environmental and social

impact of the project?

- Project Risks: What are the risks involved in the project?

- Proposed PPP Model: What PPP model would be used for this project?

Following conceptualisation, the next step is to assess the viability of

undertaking a land administration project as a PPP. Further detail on

Concept Viability Assessment is available in the Operational Framework

component of the Public-Private Partnerships in Land Administration:

Analytical and Operational Frameworks (World Bank, 2020). It is in this

step that the availability and quality of data to provide a sound

viability basis becomes evident – reemphasising the need for gathering

this data at the Land PPP Concept stage. The absence of data, too,

provides information in itself – what data is missing and why, what

processes are necessary to start collecting/collating this information

(as a preparator step to a Land PPP), and is there political will to

make such information publicly and/or commercially available. There are

tools available to assist governments and staff to collect this data,

including CoFLAS (UN-HABITAT, 2015) and the World Bank’s Land Governance

Assessment Framework (Deininger, Selod and Burns, 2011)

A key component of assessing concept viability (the next step) is

determining the commercial feasibility and appetite for involvement.

While a Land PPP project concept may make sense from a government

perspective, and may demonstrate technical validity, it is critical for

a concept to also demonstrate a degree of commercial feasibility as the

project is developed. This will be explored in the following section.

4. PRIVATE SECTOR APPETITE FOR PPP's

For a PPP transaction to be attractive to potential private sector

operators and investors, the project should demonstrate commercial

feasibility. To do so, estimated project inflows should cover projected

project outflows. Essentially, the revenues and funding for the project

should be able to cover all capital expenses (CAPEX), operational

expenses (OPEX), financial obligations (interest, debt service, and

equity paybacks), and taxes. In this context, CAPEX includes (but may

not be limited to) the following: development of IT solutions;

investment in first registration and/or digitization of land records;

purchase of equipment, vehicles, and furniture; the costs of fitting out

offices and facilities; and the purchase of buildings. OPEX, on the

other hand, refers to operational and maintenance costs. This could

include staff salaries, trainings, office rent, consumables (such as

field supplies and office supplies), and the maintenance of IT systems.

4.1 Financial Modelling for Pre-Feasibility

A pre-feasibility or feasibility study should be undertaken to

accurately determine these calculations. Project preparation must

include financial modelling for various scenarios to calculate the total

inflows and outflows over the life of the project. The accuracy of this

analysis is dependent on the validity and availability of data to inform

model assumptions (such as those informing the calculation of revenue

amounts and costs over the life of the project). The payment mechanism

proposed under the project structure will require different forms of

analysis – primarily either a user-pays or a government-pays payment

mechanism. The PPP Reference Guide 3.0 (World Bank et al, 2017) defines

these two models as follows:

- User-pays payment mechanisms are where “the private party

provides a service to users and generates revenue by charging users

for that service. These fees (or tariffs, or tolls) can be

supplemented by government payments—for instance, complementary

payments for services provided to low-income users when the tariff

is capped, or subsidies to investment at the completion of

construction or specific construction milestones. The payments may

be conditional on the availability of the service at a defined

quality level.”

- Government-pays payment mechanisms are where “the government

is the sole source of revenue for the private party. Government

payments can depend on the asset or service being available at a

contractually-defined quality (availability payments)—for example, a

free highway on which the government makes periodic availability

payments. They can also be volume-based payments for services

delivered to users—for example, payment from hospital care

effectively delivered.”

(World Bank et al., 2017)

Such mechanisms may be augmented via bonuses, penalties or fines due

as specified outputs or associated standards are – or are not – met.

4.2 Commercial Feasibility Assessment

The results of financial modelling analysis will inform the

commercial feasibility assessment, which will reflect the overall

attractiveness of the project to the private sector. The commercial

feasibility assessment considers two perspectives – debt providers and

equity providers.

4.2.1 Debt provider perspective

Debt, or lenders, scrutinize the bankability of the project, which

measures the ability of the project to service and repay debt in line

with set terms. In assessing bankability, the level of revenues and

total amounts required to service debt, available collateral security,

and stability of revenue are considered. Specifically, appraisal studies

look at the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR), which examines if the

project can generate profits capable of servicing debt each year over

the duration of the project. The Loan Life Coverage Ratio (LLCR) and

Project Life Coverage Ratio (PLCR) are also analysed, which examine the

Net Present Value (NPV) of cash flows and the outstanding debt over the

project duration (with LLCR considering ratio over the duration of the

loan and PLCR considering ration over overall project life). (ADB et

al., 2016)

4.2.2 Equity provider perspective

Equity providers, on the other hand, are investors. Investors

consider not only the bankability of the project, but also the estimated

returns of the project. From this lens, the Net Present Value (NPV) of

the project must be calculated with consideration of the Internal Rate

of Return (IRR) and discounted cash flow. The results of this analysis

should meet the minimum rate of return expected by equity investors –

the so-called “hurdle rate”. Project risks will impact these

calculations, with higher risks incurred by the investor resulting in

the desire for higher returns or additional guarantees from the public

sector partner or other implementing partners, such as bilateral and

multilateral donors.

4.3 Financing and Payment Approaches to Improve Private Sector

Appetite

If the Land PPP concept is not commercially sustainable (e.g., due to

low demonstrated revenue) but there are clear reasons to adopt a PPP

approach (e.g. to implement process efficiencies, bring in technical

skills) then governments may wish to consider mechanisms to improve

commercial appeal. Consideration and design of these steps would be

informed by the results of the pre-feasibility and/or feasibility

studies, in particular the level and degree of government funding inputs

required to make the project commercially viable. Support to improve

private sector appetite would typically only be expected when a project

is expected to have a significant economic, environmental, or social

impact, but financial returns are relatively low. It should also be

noted that fiscal regulations may also limit the extent to which direct

funding mechanisms by public authorities can be used.

Examples of government and hybrid (government and user) payment

mechanisms include viability gap funding, sovereign guarantees, service

payments, availability payments, grants, and subsidies. An overview of

these mechanisms is included below:

- Availability payments are based on ongoing service provision or

transactions. For example, a private partner might deliver and

administer infrastructure for a public authority and be compensated

via regular, performance based (i.e.: level and quality of service,

depending on agreed terms) payments. Such payments might also

include gender and pro-poor key performance indicators.

Alternatively, and mirroring approaches adopted for other

infrastructure and service PPPs, compensation could take the form of

an availability payment per transaction, with the intent to

ultimately cover total project cost – including financing and

investor returns.

- A system of guarantees for transactions in land administration

systems can be established in a manner that bounds responsibility

and provides certainty to private sector operators. Guarantees can

be provided based on professional liability insurance, gap financing

through development partners and/or existing or newly developed

public guarantee systems (eventually financed through user fees).

- Viability gap financing (i.e.: where user or government-pays

and/or hybridised models of these prove insufficient) might come in

the form of a capital grants or subsidies, payments for preliminary

necessary services or other mechanisms that address commercial

appetite, reduce the initial financier/private party investment

and/or enable lower costs to be passed along to users. Viability gap

financing is a particular area for development partners to play a

role in Land PPPs, and financing can be tied to contractual or

structural elements that support equitable or other aims. For

example, governments needing to undertake first registration or

digitization work with the private operator prior to establishing

and/or upgrading the land administration system, may seek support to

fund the commercial viability gap from a development partner.

Viability gap financing is also relevant where private partners need

additional confidence in overcoming key project risks – for example,

where a culture of formal land registration has not been

established, and revenue generation from land administration service

fees is considered a significant uncertainty by the private sector.

Viability gap financing through development partners could

particularly play a role in supporting the development of

pre-feasibility and feasibility assessment studies.

Fundamentally, mechanisms such as the above may form part of a

multitude of blended finance solutions that increase the viability of

Land PPP projects and enable inclusive targets that have been

historically atypical in commercial projects.

4.4 Coming to a Common Understanding for Land PPP investment

The greater the commercial returns, the more investor interest will

be generated. Strong market interest will enable a competitive

procurement process among a pool of qualified bidders, which is

essential to increasing the likelihood of receiving technically sound

and cost-competitive proposals.

Accurately assessing the commercial feasibility of transactions is a

common challenge for public entities considering a PPP, especially

within the land sector. It is not enough for a project to just breakeven

over the duration of the project. Investors and private partners need to

obtain a reasonable return when considering the opportunity cost of

failing to invest in other more lucrative ventures. Unless a clear

business case underpinning the commercial viability of a given project

is established before procurement, it is likely that market interest

will remain limited at best.

Conflating the economic value and the commercial value of projects is

common among land agencies, leading to misunderstandings of the

investment appetite of the private sector for certain projects. A

project of high economic value does not necessarily also have a high

commercial value. This understanding of the commercial case for a

project is critical for governments considering PPPs in land

administration and should be used as a lens when considering potential

partnerships with the private sector. The fundamental motivation of an

investor is not to optimize the economic impact of a project – it will

be to generate profit. Consequently, careful project appraisal and

structuring are imperative to properly understanding the financial

footprint of any given investment. Moreover, clear and comprehensive

obligations and standards of service are critical to contractually

addressing concerns over rights and responsibilities and risk allocation

(such as the coverage of low turn-over rural areas, for example).

Contractual incentives and penalties can be tied to the private partner

meeting certain milestones or key performance indicators (KPIs).

Drafting a contract with these stipulations and assignments of roles and

responsibilities is fundamentally dependent on rigorous project

appraisal and structuring.

5. UNDERSTANDING THE RISKS AND ALTERNATIVES TO LAND PPPs

The following section draws upon the Land Administration

Information and Transaction Systems: State of Practice and Decision

Tools for Future Investment, prepared for the Millennium Challenge

Corporation (Land Equity International, 2020).

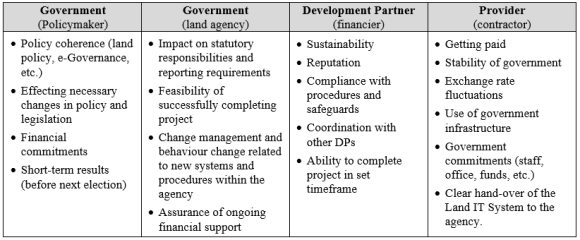

5.1 Understanding stakeholder risks to Land PPPs

Whilst only briefly mentioned above, risk is a key component of

private sector appetite that needs to be understood when considering

investments in land administration systems. Risks may include those

typically associated with investments in information technology – for

example, issues arising from unclear and changing scope, schedule,

resources and technology. They may also be associated with the typical

timeline of development partner projects (if involved) or related to

general institutional risks, including legislative gaps,

incomplete/poorly maintained existing systems, limited technical and

other resourcing capacity, etc. A State of Practice publication

developed for the Millennium Challenge Corporation (LEI, 2020) briefly

summarises the major risks to stakeholders of investing in land

administration system projects. REF _Ref67317009 \h Table 1 recognises

the different perspectives on the risks of investing in land

administration systems (noting the emphasis in the document on

technology projects). These risks should be considered upfront during

identification, feasibility and design stages of a project, though many

associated with the Provider may ultimately be addressed through project

implementation. For example, national governments will wish to consider

the extent of coherence with existing policies and will likely have

decision-making impacted by election timeframes. Similarly, development

partners will also be restricted by typical project timeframes and will

further wish to ensure initiatives that demonstrate sustainability and

compliance with safeguards. Providers, on the other hand, will want to

see demonstrated certainty around payment measures, government

commitments and handover measures (as appropriate). The list of risks in

Table 1 is not intended to be comprehensive, instead it provides an

overview of the different risks, and perspectives on risk, that need to

be taken into consideration within a PPP, and, furthermore, within a PPP

that seeks additional development partner support.

Table 1: Example risks by stakeholder perspective

5.2 Understanding Land PPP Alternatives to Finance Land

Administration Services

The financing of land administration services, and mechanisms to

prepare to do so, is covered extensively in the Costing and Financing of

Land Administration Services Land Tool (UN-Habitat, 2015) and discussed

in Section 5.3 of the State of Practice Paper (Land Equity

International, 2020). Based on international experience, an efficient

land administration agency that provides affordable and valued services

can generate significant revenue from user fees and charges – and

typically much more than the expenditure necessary to maintain the

systems and provide services to government and users. It is hence

entirely possible for land administration agencies to become

self-financing, and achievement of this can be realised through

restructuring of the agency to become semi-autonomous (with a degree

from freedom from standard civil service procedures and flexibility to

adopt new practices in line with self-sufficiency) or state-owned

enterprises (with possible external support or subsidy for services

deemed to have a public good, and recognising the need for a supervisory

board, or similar to set and approve user fees and charges, and set

annual busines plans and budgets). The success of self-financing

agencies has been seen in World Bank-funded land sector projects in the

European and Central Asia (ECA) region.

6. CONCLUSIONS - IS YOUR JURISDICTION READY?

The breadth of land administration services, combined with the

complexities of land administration in developing countries and existing

practice, demonstrates how important a clear Land PPP concept is to

ensure the right commercial partner and promoting future success. Even

more important, is ensuring that there is adequate information available

to formulate the concept, recognising the need to be commercially

attractive. Cognisant of the knowledge gap that exists around Lands,

this paper targets the conceptualisation of Land PPPs to provide a clear

picture to national and sub-national governments on the steps required

for a Land PPP proposal and the preliminary information needed prior to

further PPP life-cycle design steps.

To successfully operationalize PPPs in land administration, it is

critical to examine and assess the commercial feasibility of each

proposed transaction inclusion. By considering the perspectives of debt

and equity providers, governments can understand the underlying market

interest for the proposed project and consider potential structuring

options to optimize the chances of a competitive and successful bidding

process.

To do so, governments must conduct investment due diligence and

market sounding during project structuring and appraisal.

Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies can provide the required

datasets to inform critical decisions regarding the project payment

mechanisms and risk allocation. These analyses rely on the accuracy and

availability of data to inform key assumptions underlying the financial

modelling. When local capacity is lacking to prepare the necessary

indicators and reports, external advisors (including through development

partners) can be engaged to provide technical advisory support. However,

access to agency data remains essential. This preparation will also lay

the basis for the formulation of the PPP contract encompassing the

allocation of responsibilities and obligations and standards of service,

which will guide implementation throughout the project duration.

So, is your jurisdiction ready? The answer depends on the outcomes of

your preliminary analytical assessment. National or sub-national

governments considering a Land PPP should commence first with a

Readiness Assessment (see World Bank, 2020, p.75) before proceeding to

the Conceptualisation that this paper discusses. Once the Land PPP

concept is developed, still further work is necessary to ensure concept

viability. This preparatory work, getting into the detail now – and

ensuring the quality and availability of underlying data – will provide

the foundations for successful partnerships in the future. Underlying

all PPPs is consideration of both governments and the private sector

perspectives, and importantly, understanding the investment motivations

to optimally structure PPP transactions within the land administration

sector.

REFERENCES

- ADB, EBRD, IDB, IsDB, and WBG. 2016. The APMG Public-Private

Partnership (PPP) Certification Guide. Washington, DC: World Bank

Group, p 38.

- Deininger, Klaus, Harris Selod, and Anthony Burns 2011 The Land

Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and monitoring good

practice in the land sector. The World Bank, 2011.

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2008 Concession

Laws Assessment 2007/8 Core Analysis Report. Final Report July 2008.

Available at

https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/legal/concessions/conces08.pdf

Accessed 17 March 2021

- HM Treasury 2010 Joint Ventures: a guidance note for public

sector bodies forming joint ventures with the private sector.

Available at:

https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130102211814/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/joint_venture_guidance.pdf

Accessed 19 March 2021

- Land Equity International 2020 Land Administration Information

and Transaction Systems: State of Practice and Decision Tools for

Future Investment. Report prepared for the Millennium Challenge

Corporation. Available at

https://www.landequity.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/LAND-INFORMATION-AND-TRANSACTION-SYSTEMS-STATE-OF-PRACTICE-FINAL.pdf

Accessed 12 March 2021

- UN-HABITAT 2015 Costing and Financing of Land Administration

Services in Developing Countries. Report prepared by Land Equity

International for the Global Land Tool Network. Available at

https://www.landequity.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CoFLAS-Report-FINAL.pdf

Accessed 16 March 2021.

- World Bank PPP in Infrastructure Resource Centre for Contracts,

Laws and Regulations (PPPIRC) 2008 Joint Ventures (Empresas Mixtas)

– Checklist of Issues Available at

https://library.pppknowledgelab.org/documents/1589/download

Accessed 19 March 2021

- World Bank 1998 Concessions for infrastructure: A guide to their

design and award. Work in progress for public discussion. A joint

production of the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank.

Available at

https://library.pppknowledgelab.org/documents/1689/download

Accessed 19 March 2021

- World Bank 2016 The State of PPPs. Infrastructure Public-Private

Partnerships in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies 1991-2015

Available at

https://ppiaf.org/documents/3551/download Accessed 9

October 2019

- World Bank 2017 Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide,

Version 3. Available at:

https://library.pppknowledgelab.org/documents/4699

Accessed 9 October 2019

- World Bank 2020 Public-Private Partnerships in Land

Administration: Analytical and Operational Frameworks. World Bank

Available at

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34072 Accessed

16 March 2021

- World Bank PPP LRC 2020 Joint Ventures / Government Shareholding

in Project Company World Bank PPP Legal Resource Center. Available

at

https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/agreements/joint-ventures-empresas-mixtas

Accessed 13 March 2021

- World Bank Group, ADB, EBRD, GI Hub, IADB, IsDB, OECD, UNECE,

and UNESCAP (2017). Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide,

Version 3. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, p 8

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Tony Burns is the co-Founder of Land Equity

International and has extensive experience in the design, management and

evaluation of land titling and land administration projects. Mr Burns

has over 30 years’ management experience, including experience as a team

leader and project director, supervising large-scale, long-term,

multi-disciplinary projects. He has undertaken numerous short-term

consultancy projects for the World Bank, AusAID and ADB. His technical

expertise extends across land policy, cadastral survey and mapping, land

titling, land administration and spatial information systems.

Fletcher Wright is the Managing Director at Planet

Partnerships, a firm exclusively dedicated to supporting governments,

international financial institutions (IFIs), and private investors

identify, structure, finance, and implement investments and partnerships

in every sector.

Kate Fairlie is a land administration specialist

with Land Equity International and has some 15 years of experience at

the nexus of urban land issues, technology, participation, youth and

environment. As an experienced researcher, writer, and facilitator, she

has been instrumental to the development and promotion of a number of

key land administration tools. She holds an MSc in Sustainable Urban

Development from the University of Oxford.

Kate Rickersey is the Managing Director of Land

Equity International and former Team Leader of the Mekong Region Land

Governance project. Kate has provided strategic technical advice on many

projects internationally, with extensive experience across land

administration, customary tenure, systematic regularization, social and

gender safeguarding, governance and evaluation. She holds a doctorate in

land administration from the University of Melbourne.