What People Want

Chris WILLIAMS-WYNN, South Africa

|

Chris Williams-Wynn

|

1)

This paper was presented at the FIG Working Week in

Sofia, Bulgaria, 17-21 May 2015. Land administration in South Africa is

an interesting study because it consists of a dual system that has

promoted investment in areas where private property rights were

permitted, but relegated the Traditional Communities into poverty and

disinvestment. The paper shows that the concept of ownership, land

rights and title deeds goes much further than the ability to buy and

sell property.

SUMMARY

Notwithstanding the minority of authors that disagree, most research

has shown that private property rights provide far greater incentive for

an individual to create wealth and preserve the value of his/her assets

than State or communal ownership does. In South Africa, policies of

separate development and restrictions placed on capital expenditure

imposed on the lands occupied by the indigenous people during the

colonial era prevented the state from implementing the Cadastre in the

communal areas of the country. The status quo persists to this day,

which has resulted in a dual system that promoted investment in areas

where private property rights were permitted, but relegated the

Traditional Communities into poverty and disinvestment.

By observing the layout of rural communities, it is evident that

people have made an effort to define the boundaries of their land rights

through the erection of fences, hedges, stones and other visible

features. In this study, therefore, the representative sample of

community members provided a broad indication of what people living in

Traditional Communities across South Africa wanted in terms of land

rights. The results were twofold:

- Firstly, members of traditional communities were seldom

interested in land as a marketable commodity: community members

perceive themselves as the current custodians of land belonging to

their ancestors, the living and the members of the community still

to be born. This is supported by findings of other researchers such

as in Goodwin (2014, pp.9–10).

- Secondly, members of a traditional community primarily want

identity. They want to be identified with the land they occupy.

Each one wants documented evidence that links him or her to the land

that he or she was born to share. Each person wants proof that

indicates: “this is our land, my land; we belong, I belong!”

Settlement Patterns of a Rural Village on Communal Land near Mount

Frere, Eastern Cape

Photo: Mark Williams-Wynn

INTRODUCTION

The Government of South Africa recognises 12 monarchs and 774 other

Traditional Leaders (Department of Provincial and Local Government,

2002, p.39). Traditional Communities have been allocated approximately

15.5 million hectares of communal land for occupation under these

Traditional Authorities, which equates to 13% of the country. It is

estimated that there are 15 million people (between 30% and 40% of the

South African population) who either live in these Traditional

Communities (Department of Land Affairs, July 2004, p.12) or perceive

the communal area to be their “home” (Goodwin, 2014, p.2). Apartheid

settlement patterns in South Africa have resulted in extra-legal

“rurbanisation”, where less-formal urbanisation has taken place in rural

confines. Lack of infrastructure (including legal structures) and

resources in these rural areas has resulted in suffering, need and

dependency (FIG, August 2004, p.14).

Seldom is this land occupation recorded in any form of land right,

even outside the formal land administration system. The lack of legal

recognition of ownership of the land that these communities have

occupied for generations may have resulted in unwillingness of members

of those communities to invest time, effort or capital into the land

they call their own. It certainly cannot be viewed as a capital asset.

Yet, well-defined boundaries of fences or hedges, which surround many

homesteads in these communal areas, indicate an informal yet recognised

exclusivity and right of use. The South African Government’s own

Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative (ASGISA, 2006, p.14) recognises

that land remains an unusable or “dead” asset until land tenure is

instituted and formalised. Property rights are one of the

market-supporting institutions missing in the communal areas and,

because they are a missing component of the infrastructure that promotes

economic development, they limit private-sector investment

opportunities. Therefore, one of the keys to local investment in

communal areas is the creation of tenure security for the people who

have occupied their family allotments for generations.

Hedges identifying homestead boundaries on Communal Land near

Mbazwana, KwaZulu-Natal

Photograph: Justin Williams-Wynn

In support of this contention, Heitger (Winter 2004, p.384) argues

that the promotion of economic development without well-defined private

property rights (as was attempted in the Soviet Union) turned out to be

“very costly in terms of life, personal liberty and economic

prosperity”. Zirker (Summer 2005, p.127), writing about inequities in

ownership in Brazil, notes that ownership is a privilege of the elite

and that landlessness is the lot of the masses, and voices the demand

for a re-evaluation of the distribution of property ownership.

Further, and particularly in Western countries, the owner of a land

right can use his or her title deed as security with a financial

institution in order to raise a loan (Blair et al, 2005, pp.50–52).

Land rights have worked in the West, and they have worked in South

Africa: through the generation of active capital from formal property

rights, many South Africans have realised their dreams of improved

economic security. Conversely, those who do not have anything but

insecure tenure perceive that the Traditional Community provides them

with little more than some form of social security (Goodwin, 2014,

pp.5–6).

Section 25 of the South African Constitution (Republic of South

Africa, 1996) clearly states that: “no law may permit arbitrary

deprivation of property”? The Constitution further places an obligation

on Parliament to ensure, through the enactment of legislation, that all

people and communities are provided with secure tenure. It therefore

seems illogical (at least to the researcher) that the South African land

administration system still retains what Mamdani (Fall/Winter 2002,

p.53) refers to as the “bifurcated legal structure” created by the

colonial practice and apartheid laws of the former regime.

Fences separating a homestead from a communal tap near Mseleni,

KwaZulu-Natal

Photograph: Justin Williams-Wynn

THE DEMAND FOR PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS

The Land Summit meetings held throughout South Africa during the

middle of 2005 indicated overwhelmingly that the people of South Africa

want to own land. One reason, as Nonyana twice states in her article on

resolving tenure disputes in rural communities (Nonyana, June 2004, p.3,

7), is that “Land ownership is associated with power.” Mobumbela, in

discussion with authors Kayser and Adhikari (2004, p.330) declares that

“when it came to the question of land, people were prepared to die.”

These perspectives are understood in the context of property rights

being, according to Zirker (Summer 2005, pp.129–130), a “legal,

equitable, or moral title or claim to the possession of property” and

the “enjoyment of its privileges … [free] from interference by others,

particularly the government”.

de Soto’s hypothesis of why capitalism has failed everywhere except

in the West (de Soto, 2001, p.55) argues that the reason for its success

is that only in the West is property easily tradable and transferable.

Hanlon (September 2004, p.612–614), however, questions whether it is

exclusively the western-type freehold title as proposed by de Soto that

increases efficiency in the land market? Instead, he suggests that the

World Bank’s policy (i.e., Deininger, 2003) dismisses de Soto’s

hypothesis. Nevertheless, de Soto’s record of historical fact still

stands: the United States was no better off in the 19th century than is

Africa today (de Soto 2001, pp.15–16). Their pioneers were seldom more

than adventurers and fortune-seekers; yet, once the United States

government of the day had recognised the claims of the settlers as

legitimate land rights, the new owners had a greater incentive to invest

in their land, which has supported the US in becoming the economic power

it is today (Deininger, 2003, p.27).

The same is evident in South Africa. All that the Afrikaner people

had left after the ravages of the Anglo-Boer wars was their land

rights. What the British had not confiscated, they had burnt or

destroyed. Yet, within a few decades, admittedly with the support of

discriminatory legislative measures, much wealth was re-established from

the land. Conversely, in Traditional Community Areas, where still no

land rights are formally documented even after 20 years of democracy,

people largely remain in abject poverty. Ralikontsane (2001, p.69)

argues that secure land rights are a necessary component of an effective

land administration system and Kifle, Hussain and Mekonnen (June 2002,

p.16) propose that good governance seeks to “create an enabling

environment for the private sector—by ensuring respect for property

rights and by creating legal and judicial systems that enforce

contractual obligations and create a level field for private

enterprise.” Another argument given by Blair et al. (2005, p.231) is

that “effectively enforced property rights are important for reducing

investment costs and risks…”

Amidst much ideological opposition, the United States inculcated the

concept of private property rights into the Third World during the

1960’s and 1970’s through its foreign policy influence. The reasons for

the promotion of land rights into the Third World were many, including

the policy of undermining socialist ideologies and the means by which

their investments in African territories could be protected from

nationalisation and state intervention. Over the years, these policies

have evolved and, currently, the global community perceives that the

primary objective of any land policy should be sustainable development

(FIG, August 2004, p.16). Therefore, much of the historic opposition to

property rights (as epitomised by countries such as Cuba and Nicaragua)

is currently weakening and, according to Zirker (2005, p.126), even the

Chinese Communist party has recently announced that “private property

rights ‘legally acquired’ are inviolable.”

Fences defining boundaries on Communal Land near Qunu, Eastern Cape

Photo: Mark Williams-Wynn

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS

Nevertheless, there are some dissenting voices to the clamour

for property rights. Zirker (2005, p.126) argues that property rights

are essentially a Western capitalist concept and this is supported by de

Soto’s hypothesis of why capitalism has failed everywhere except in the

West (de Soto, 2001, p.55). A reason given for the success of

capitalism in the West is because capitalism works best where property

is easily tradable and transferable (PLAAS Policy Brief, October 2005).

However, in a market economy, the poor are the most vulnerable and often

their only means of generating capital is through the sale of their

property. Even though they may own the land that they occupy, they do

not have the means to secure credit and they seldom have the capacity to

repay a loan. The PLAAS policy brief therefore argues that individual

ownership actually decreases the security of tenure of many occupants.

This position is supported by reference to a study carried out in an

economic housing development in Joe Slovo Park, Cape Town. Hence, PLAAS

believe that the property market promotes capitalism at the expense of

livelihood security of the poor.

In another investigation into communal land rights, this time in

Mexico, Munoz-Pina (October 2003, p.130), cautions that the cost of

privatisation can exceed the expected benefits. Firstly, there is a

scarcity of willing buyers of land in communal areas and, secondly, the

actual realisable land value is still very limited. Even with economies

of scale, the values of land parcels are unlikely to warrant the

expenditure and, further, the benefit would be spread unevenly,

depending on where the demand is. Also, Munoz-Pina is concerned that

community life, which provides “other advantages such as information

sharing, mutual insurance and political clout” – i.e., collective action

– would be destroyed. Amin and Thrift (in Harrison, 1994, pp.84–85)

also have negative perceptions when they consider that: “… efforts to

regenerate the local economy through locally regulated ventures … run

the risk of doing little more than legitimising a false belief in the

possibility of achieving solutions for what are global problems beyond

local control …” They continue: “Somewhat bleakly then, we are forced

to conclude that the majority of localities may need to abandon the

illusion of the possibility of self-sustaining growth and accept the

constraints laid down by the process of increasingly integrated global

development.”

Fences and hedges defining boundaries on Communal Land near Tsolo,

Eastern Cape

Photo: Mark Williams-Wynn

Are these truly justifiable reasons to oppose private property

rights? It is common knowledge that there are huge variances in the

monetary value of property, depending on its location and its useful

resources. However, the author supports the contention of Azhar

(October 1993, p.118) that land has no value at all to the occupant

until he or she has the right to own and to trade it and to harvest the

resources it provides. Even so, much of the value of the land is

determined by the land market, which is not concerned about the

livelihood security of the occupant, especially where the occupant is

very poor! In all three cases – that of PLAAS, Munoz-Pina, and Amin and

Thrift, therefore, very valid concerns are raised, but their concerns

should be matters to protect against when creating land rights, rather

than being reasons not to issue private property rights.

BENEFITS OF TENURE SECURITY

This research needed, therefore, to look beyond the market value and

tradability of land. UN-Habitat’s document entitled “Global Campaign

for Secure Tenure” (1999, p.7) advocates secure tenure because the body

believes that it ensures there is progressive and sustained improvement

in the living conditions of the beneficiaries. Further, the provision

of secure tenure advances the fulfilment of Target 11 of Goal 7 of the

Millennium Development Goals – “to achieve a significant improvement in

the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by the year 2020”

through increasing the “proportion of people with secure tenure” (i.e.,

Indicator 31) (UN-Habitat, 2003, p.26). Subsequent to the Millennium

Development Goals, the United Nations established an Open Working Group

(OWG) of Sustainable Development Goals to define agreed goals for the

post-2015 Agenda. The OWG has developed 17 goals with 169 targets.

Proposed Goal 1, target 4, reads: “By 2030, ensure that all men and

women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to

economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and

control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural

resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including

microfinance” (Open Working Group, 2014, p.7).

While UN-Habitat literature referred to above may have had its focus

on urban areas, it is important to note that urbanisation of many

Traditional Community areas is taking place, especially where they are

in closer proximity to existing metropolitan areas. These are

highlighted in the research by Mogale, Mabin and Durand-Lasserve (April

2003). Secondly, if the lack of security of tenure is a limiting factor

in urban areas, how much more so in the rural parts of the Traditional

Community areas, where occupants have very little other than a tenuous

right to build a homestead and whose livelihood is gleaned from a

communal share in the land? For this reason, the Public Service

Commission Report (2003, p.10) highlights the fact that any tenure

system should exist primarily as a protection for the poor, who have no

other mechanism to defend their occupational rights, and, as PLAAS

(October 2005) emphasises, not as a marketable commodity.

More than leaving the poor at the mercies of the capitalist market,

this formal recognition of occupation provides legal protection, and

hence diminishes the fear of forced eviction (UN-Habitat, 2003, p.28);

it provides the right holder with “status and citizenship” (ibid, p.7)

and it provides equal rights for all, as it provides a mechanism to

overcome discriminatory practices (ibid, p.32). Secure tenure is also

one of the most important catalysts for, firstly, attracting large-scale

capital necessary for comprehensive slum upgrading and, secondly, to

encourage the urban poor themselves to invest in their own dwelling and

communities (ibid, p.28).

There are other benefits that this research has also considered.

Deininger (2003, p.27), on behalf of the World Bank, supports the notion

that land tenure is beneficial with his argument that legitimate land

rights provide an incentive to invest. People are more likely to sink

personal time and effort (and not just financial investment) into

something when they know that they will enjoy the benefit thereof. In

addition, Wood (May 2002, p.30) asserts that, “The best way to moderate

inequality is to spread the ownership of productive assets more

widely.” Wood (ibid, p.21) also argues that the institution of private

property rights reduces the risk in non-commercial investment. Further,

Durang and Tanner (2004, pp.1–9), in their paper on “Access to land and

other natural resources for local communities in Mozambique”, give the

following benefits of security of tenure, based on their research:

- it places resources in the hands of the people;

- it gives people the ability to invest and respond to market

dynamics;

- it provides an incentive to invest scarce resources in the

protection and conservation of the land and its natural resources;

- it gives to the people who sacrifice time and effort the right

to reap the benefit;

- it protects the right to the exclusion of others;

- it provides a public de facto resource inventory;

- it involves the communities as stakeholders in any new

development initiated by external parties; and

- it limits the ability of outsiders (especially government

officials) to allocate rights without community support – hence

placing a check on corruption and rent-seeking activities.

Enemark et al (2014, p.14) summarises all of the above by concluding

that: “Sound land administration systems deliver a range of benefits to

society in terms of: support of governance and the rule of law;

alleviation of poverty; security of tenure; support of formal land

markets; security of credit; support for land and property taxation;

protection of state lands; management of land disputes; and improvement

of land use planning and implementation.” All these examples provide

substantial support to the suggestion that secure tenure is beneficial

to those afforded it, but in particular to poorer people. The arguments

therefore swing in favour of clearly documented and identifiable land

rights that provide secure tenure for the people.

RESULTS OF INSECURITY

On the other hand, people deprived of secure tenure have no means of

securing their assets and are therefore held in the grips of poverty.

Wood (May 2002, p.30) argues that, “In a land-abundant developing

region, the most obvious asset is land itself. The extremely unequal

distribution of land in colonial times was a root cause of Latin

America’s chronic income inequality”. Moreover, the World Bank

Investment Climate Surveys (World Bank, 2005, p.43) indicate that,

firstly, cost, secondly, access to finance and, thirdly, access to land

are three constraints that have had a negative impact on private sector

activity. Further, “… although significant improvements have been made

in the provision of services, the poor remain deprived of many public

[facilities] necessary for entrepreneurial activities (such as property

rights, public safety and infrastructure), and incur high costs in time

and expense when trying to obtain these” (Gantsha, Orkin and Kimaryo,

2005, p.51). Until this happens, the traditional areas will remain

within the realms of the informal economy, excluded from information,

development, business services and access to credit. Simply put, people

are less likely to invest in their property if it is not theirs!

Yet, land rights alone do not generate wealth (Braithwaite, 2007,

p.9). Demanding expenses of agricultural activities and the

unpredictability of external forces such as drought and floods have sunk

many aspirant farmers. Knowledge, skills and capital are all essential

additives to reduce the risk of failure, and these are scarce amongst

the poor. Nevertheless, without secure property rights, there is even

less chance of success.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

While the author is convinced of the benefits of the security

afforded to people by a land tenure system, it still needed to be

determined if this is what people who occupy land with insecure forms of

tenure actually want. Therefore, the author, with assistance from a

team of fieldworkers, interviewed individuals who either lived

permanently in a Traditional Community or considered a communal area to

be their “home”. Leedy and Ormrod (2005, p.207) suggest that, for a

large population, a sample size of 400 should be adequate. (Estimates

mentioned earlier suggest that the communal areas have a population of

around 15 million) In this research, a total of 717 responses were

received, which is considered to be representative of all members of

Traditional Communities of South Africa. In addition, several

photographs, taken by the author and his family during journeys made

through the Traditional Communities in the Eastern Cape, Free State,

KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga, add external observation that complement

the findings of the research. The photographs provide widespread

observational evidence of the existence of informal land tenure rights

where none are documented in a formal land administration system.

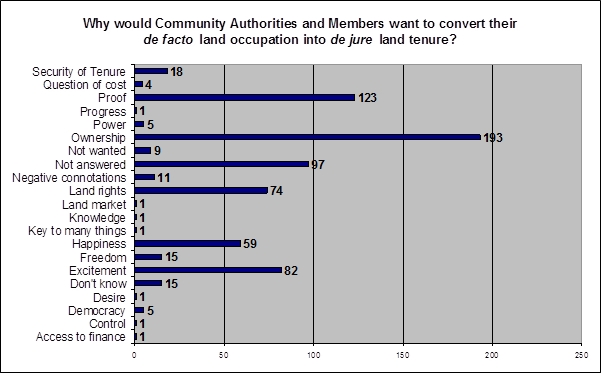

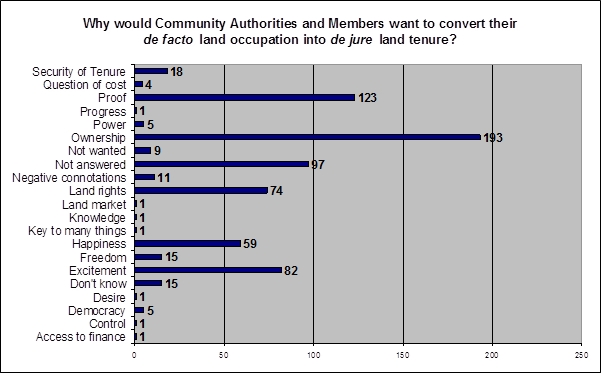

The research ascertained whether land rights are wanted, through

seeking answers to the research question: “Why would Community

Authorities and members want to convert their de facto land occupation

into de jure land tenure, i.e., what are the perceived advantages?”.

The questionnaire endeavoured to gain further insight to the answer

through a second question: “If your family obtains a title deed to their

land allocation, what would this mean to your family?” The author made

some attempt during the capturing process to group these responses, yet

still came up with around 100 different types of answer. There were,

however, a few broad patterns and these are shown as 21 different

categories in Figure 1 below.

Of the 717 respondents, 15 respondents answered “don’t know” and a

further 97 respondents left the question unanswered. This makes up 112

of 717, or 16% of the total. A further 158 respondents (22% of the

total number of respondents) gave answers that suggested a lack of

understanding of the question, as they gave answers such as “happy” and

“yes”! It is noted that some discussion in groups took place over the

questions, as there were often several similar or identical answers from

the same community. While this may have detracted from personal

opinions, it would certainly bode well for the future of land rights if

people have already started to foster a common thinking towards their

creation. Even when the answers indicated a lack of understanding, as

shown through testing the responses further on in this research, there

is an overwhelming indication of the expectation that benefit will

result from receiving a title deed.

Figure 1: Reasons given for wanting de jure Land Tenure

Figure 2 demonstrates that 75% of all respondents gave an answer that

indicated positive sentiments toward receiving their own land rights. A

further 6% declared their interest in the concept. This is compared

with less than 7% of respondents who indicated that they are against

receiving their own land rights. The actual figures have been

summarised in the table below. Notwithstanding that 81% of respondents

indicated interest in obtaining a visible record for the land that they

occupy, a large proportion of these provided no evidence to show that

they understood the concept of land rights.

Most importantly, there were four issues that the answers

highlighted. Firstly, 17% (123 respondents) saw the demarcation and

record of land rights as some form of proof, assurance or confirmation

of ownership. Secondly, 193 respondents (27%) recognised the title deed

as providing ownership to the land that they occupy. This may be an

unintentional difference, but there is nevertheless a clear distinction

(at least in the author’s mind). The first group suggested a belief

that their occupation is tantamount to ownership of the land, and need

the documentary evidence to prove it, whereas the second group seem to

have recognised that their occupation is not ownership, but the public

record would confer ownership. These two groups combined represented

316 respondents, or 44% of 717.

The third issue that is highlighted is that only 20 of the

respondents (2,8%) stated outright that they did not want title deeds or

gave negative connotations to the concept of title deeds – such as

“oppression”, “expenses” and “the end of tribal land”. This is a small

minority, but, of course, it cannot be ignored or deemed

inconsequential. Lastly, only one respondent commented on the notion of

a land market and another respondent mentioned that it would provide

access to loan finance – often the key reasons given in the West for the

institution of land rights.

Figure 2: Interest of Community Members in receiving their own land

rights

This research shows, therefore, that the overwhelming majority of the

respondents, all of whom are members of traditional communities, desire

the conversion of their de facto land occupation rights into de jure

land tenure rights.

CONCLUSION

The results are therefore conclusive – there is an informal

allocation and demarcation of land rights in Traditional Community Areas

that can be brought into a public registry of property rights, which is

currently based on diagrams and title deeds. This research, therefore,

advocates that a key to the economic prosperity of South Africa is an

effective legal infrastructure of property rights and land

administration in communal areas that promotes the security of tenure.

At the XXIII Fédération Internationale des Géomètres (FIG) Congress

held in Munchen; Germany from 8th – 13th October 2006, Hans-Erik

Wilberg, Executive Director of the Swedish Lantmäteriet, commented that:

“Land is one of the most valuable assets and an important base for the

development of the wealth of a nation. Good land administration is

essential for the development of an effective land market and a secure

financial sector and will provide a basis for land management and land

taxation. To unlock that wealth, a nation must develop a framework of

land and property laws, effective public institutions, secured

procedures and processes and an effective information system”.

In addition to this, a good land administration system also provides

proof to the owners of their inviolable rights, protection to the owners

against unjustifiable loss, the right to the exclusion of others to

utilise the land and its resources, the right to succession of heirs,

and a unique address. But most important of all, it provides the owner

of that right an identity – a place of belonging and of self-worth! The

concept of ownership, land rights and title deeds goes much further than

the ability to buy and sell property. Some of the answers given by

people excited to receive title to the land they occupy are that it

provides visible evidence, it gives security of title, and it brings

permanence, protection and pride. Do people want land rights? The

people have spoken, and the answer is overwhelmingly: “Yes”! “Amandla

ngawethu![1]” [1] ”Amandla

ngawethu” is an isiXhosa phrase meaning “the power is ours”.

Fences defining land allocations on Communal Land near eNkambeni,

Mpumalanga

Photo: Mark Williams-Wynn

REFERENCES

ASGISA (2006), Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative – South

Africa (ASGISA) – a summary. Pretoria, the Presidency, Republic of

South Africa, pp 1 – 17.

Azhar, R. A. (October 1993), Commons, Regulation, and Rent-Seeking

Behavior: The Dilemma of Pakistan’s Guzara Forests. In Economic

Development and Cultural Change, Volume 42, Number 1. Chicago,

University of Chicago Press, pp. 115 – 129.

Blair, T. et al. (2005), Our Common Interest – Report of the

Commission for Africa. Retrieved 3rd June 2005 from

http://www.number-10.gov.uk/output/Page1.asp and

http://www.commissionforafrica.org/english/report/thereport/english/11-03-05_cr_report.pdf

Braithwaite, B. (2007), Land alone will not generate wealth. In The

Witness, Monday, March 26, 2007. Pietermaritzburg, Natal Witness, p. 9.

De Soto, H. (2001), The Mystery of Capital – Why Capitalism triumphs

in the West and fails everywhere else. London, Black Swan, pp. 14 – 68.

Deininger, K. (2003), Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction.

Washington, Co-publication of the World Bank and Oxford University

Press.

Department of Land Affairs (July 2004), End of a Colonial Era:

Questions. In Tenure Newsletter. Pretoria, Department of Land Affairs,

p. 12.

Department of Provincial and Local Government (2002), Draft White

Paper on Traditional Leadership and Governance. In Government Gazette,

No. 23984, dated 29 October 2002. Pretoria, Government Printer.

Durang, T. and Tanner, C. (March 2004), Access to Land and other

Natural Resources for Local Communities in Mozambique: Current Examples

from Manica Province. Proceedings from GreenAgriNet Conference on Land

Administration. Foulum, 1 – 2 April 2004.

Enemark, S. et al. (2014), Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration.

A joint publication by the Fédération Internationale des Géomètres (FIG)

and the World Bank. Frederiksberg, International Federation of

Surveyors, Publication No. 60.

Fédération Internationale des Géomètres (FIG) (August 2004),

Marrakech Declaration: Urban-Rural Interrelationship for Sustainable

Development. Frederiksberg, International Federation of Surveyors,

Publication No. 33.

Gantsha, M., Orkin, M. and Kimaryo, S. S. (2005), Overcoming

under-development in South Africa’s second economy: Development Report

2005. A joint report by the Development Bank of South Africa, the Human

Sciences Research Council and the United Nations Development Programme.

Halfway House, Development Bank of South Africa.

Goodwin, D. (2014), Communal land tenure: can policy planning for the

future be improved? Retrieved 6th January 2015 from

http://www.africageoproceedings.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/23_Goodwin.pdf

Hanlon, J. (September 2004), Renewed Land Debate and the “Cargo Cult”

in Moçambique. In Journal of Southern African Studies, Volume 30,

Number 3. Abingdon, Taylor and Francis Ltd, pp. 603 – 625.

Harrison, P. (1994), Global Economic Trends – Some Implications for

Local Communities in South Africa. In Urban Forum, Volume 5, Number 1.

Johannesburg, University of the Witwatersrand, pp. 73 – 89.

Heitger, B. (Winter 2004), Property Rights and the Wealth of Nations:

A Cross-Country Study. In Cato Journal, Volume 23, Number 3. Washington,

D. C., Cato Institute, pp. 381 – 402.

Kayser, R. and Adhikari, M. (2004), Land and Liberty! The African

People’s Democratic Union of Southern Africa during the 1960’s. In

South African Democracy Education Trust: The Road to Democracy in South

Africa, Volume I (1960 – 1970). Cape Town, Zebra Press, pp. 319 - 339.

Kifle, H., Hussain, M. and Mekonnen, H. (June 2002), Achieving the

Millennium Development Goals in Africa – Progress, Prospects, and Policy

Implications. African Development Bank. Retrieved 16th September 2005

from

http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/afr/afr.nsf/dfb6add124112b9c852567cf004c6ef1/aa2093d2b04d

dbd885256be30058f71c/$FILE/mdg-africa.pdf

Leedy, P. D. and Ormrod, J. E. (2005), Practical Research, Planning

and Design, eighth Edition. Upper Saddle River, Pearson Prentice

Hall.

Mamdani, M. (Fall/Winter 2002), Amnesty or Impunity? A Preliminary

Critique of the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of

South Africa (TRC). In Diacritics, Volume 32, Number ¾. Baltimore,

Johns Hopkins University Press, downloaded from Academic Research

Library, pp. 33 – 59.

Mogale, T., Mabin, A. and Durand-Lasserve, A. (April 2003),

Residential Tenure Security in South Africa – Shifting Relationships

Between Customary, Informal and Formal Systems. As yet, unpublished,

pp. 1 – 43.

Munoz-Pina, C., de Janvry, A. and Sadoulet, E. (October 2003),

Recrafting Rightes over Common Property Resources in Mexico. In

Economic Development and Cultural Change, Volume 45, Number 1. Chicago,

University of Chicago Press, pp. 129 – 158.

Myrdal, G. (1963), Economic Theory and Under-Developed Regions.

London, Methuen and Co. Ltd, pp. 11 – 22 and 39 – 49.

Nonyana, M. R. (June 2004), Resolving Tenure Disputes in Rural

Communities. In LexisNexis Butterworths Property Law Digest, pp. 3

– 8.

Open Working Group (2014) Full report of the Open Working Group of

the General Assembley on Sustainable Development Goals; UN document

A/68/970. Retrieved 8th January 2015 from

http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1579SDGs%20Proposal.pdf

PLAAS (October 2005), Policy Brief No. 18: Debating land reform,

natural resources and poverty. Cape Town, University of the Western

Cape, pp. 1 – 6.

Public Service Commission (PSC) (2003), Report on the Evaluation of

Land Administration in the Eastern Cape. Pretoria, Public Service

Commission.

Ralikontsane, K. F. (2001), The Implementation of Secure Residential

Tenure in the Rural Areas of Thaba Nchu. Johannesburg, University of

the Witwatersrand, Graduate School of Public Management, Unpublished MM

Research Report.

Republic of South Africa (1996), Constitution of the Republic of

South Africa, 1996 (Act No. 108 of 1996). Pretoria, Government Printer.

Stamm, V. (2004), The World Bank on Land Policies: A West African

Look at the World Bank Policy Research Report. In Africa, Volume

74, Number 4, pp. 670 – 678.

UN-Habitat (1999), Global Campaign for Secure Tenure: Implementing

the Habitat Agenda: Adequate Shelter for All. Retrieved 15

November 2005 from

http://www.unchs.org/campaigns/tenure/articles/tenure_the%20global%20campaign_for%20secure%tenure.html

UN-Habitat (2003), Handbook on Best Practices, Security of Tenure and

Access to Land: Implementation of the Habitat Agenda. Nairobi, United

Nations Centre for Human Settlements.

Wood, A. (May 2002), Could Africa be like America? Proceedings

of the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics. Washington

DC, World Bank.

World Bank (Wolfensohn, J. D. and de Rato R.) (2005), Global

Monitoring Report 2005. Washington, International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development.

Zirker, D. (Summer 2005), Property Rights, Democratization and

Military Politics in Brazil. In Journal of Political and Military

Sociology, Volume 33, Number 1, pp. 125 – 139.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Chris Williams-Wynn grew up in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, and

went to school at St Andrew’s College in Grahamstown. After school, he

completed a BSc (Honours) degree in Land Surveying from what is now the

University of KwaZulu-Natal and has more recently completed his Masters

in Public and Development Management at the University of the

Witwatersrand.

He is a Registered Professional Land Surveyor, a Registered Sectional

Titles Practitioner, a Registered Township Planner and a Disability

Rights Activist. Having worked for 17 years in the private sector, he

moved into the government sector due to his deteriorating physical

ability. Mr. Williams-Wynn was appointed the Surveyor-General:

KwaZulu-Natal on 1st May 1998, and transferred at his own request to

establish the Office of the Surveyor-General: Eastern Cape on 1st July

2010.

Mr. Williams-Wynn travels extensively throughout South Africa and

occasionally internationally, as he is an advisor to several Government

institutions on land issues, with particular interest in legislation

affecting development approvals. He serves on the Townships Board, the

Land Use Regulations Board and the Spatial Planning and Land Use

Management Steering Committee. One of his main passions is to see

people in the Traditional Communities also benefit from the Land Rights

system of the country.

Outside of his survey career, Mr. Williams-Wynn is interested in

environmental conservation, with special interests in birds and trees.

This interest has benefited his knowledge concerning coastal public

property and the legal position of boundaries adjoining the high water

mark of the sea, rivers and estuaries. He is also a Society Steward of

the Methodist Church and an active Rotarian. He is married to Glenda, a

Natural Sciences Graduate, currently working as a Conservation Ecology

Research Assistant and they live in Kidd’s Beach.

CONTACTS

Mr. Chris Williams-Wynn

Surveyor-General: Eastern Cape, Department of Rural Development and Land

Reform

Private Bag X 9086, East London, 5200

East London, Eastern Cape

SOUTH AFRICA

Tel. +27 43 783 1424

Fax. +27 43 726 4279

Email: Chris.WilliamsWynn[at]drdlr.gov.za

|