Article of the Month -

March 2014

|

Adjusting Laws to meet the Requirements of Urban

Expansion in a Sus-tainable Property System

Dr. Alexander KOHLI, SWISS LAND MANAGEMENT,

Switzerland

1) The paper of the month

presents a concept for Sustainable Land Management to secure a long term

successful development of informal urbanization. To create good

conditions for improving the property and planning situation, a solid

legal base has to be put in place before further land management

activities are undertaken. The author asks for the initialization of an

intermediate legal frame-work as an initial step to be applied to a

special perimeter of action, the so-called 'temporary development zones'

TDZ. This paper was presented at the Annual World bank Conference on

Land and Poverty, in Washington DC, April 8-1, 2013. You can hear Dr.

Alexander Kohlis presentation at the XXV International FIG Congress 2014

in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Key words: Urban expansion, land management, fast documentation,

spatial planning, temporary development zones.

ABSTRACT

In metropolitan areas the informal urbanization of the outskirts is a

classic practice. Today it must be accepted that a large number of the

regulatory tools available for managing urban development are not

necessarily appropriate to be applied as they are in many developing and

transitional countries where the rule of law leaves a lot to be desired.

In consequence, the large majority of urban authorities often do not

engage in realistic preparations for growth.

The two known approaches in this field, the set-up of regulatory

measures on the one hand and the public initiatives on the other, are

commonly accepted but do not necessarily lead to success. Looking at the

initiatives approach it becomes clear that the need for a sufficiently

consolidated property system to gain long term success is

underestimated. A formally correct situation without conflicting

property rights and disputed land titles remains a pre-condition not

only for enabling land and housing markets but also in view of securing

land for public needs, assuring sites and services in the framework of

public initiatives (Sustainable Land Management). To create good

conditions for improving the property and planning situation, a solid

legal base has to be put in place before further land management

activities are undertaken.

The presented concept, therefore, asks for the initialization of an

intermediate legal frame-work as an initial step to be applied to a

special perimeter of action, the so-called 'temporary development zones'

TDZ.

1. INTRODUCTION

In metropolitan areas of southern, transitional, or post-conflict

countries, the informal urbanization of the outskirts is a classic

event. Today it must be accepted that a large number, if not most, of

the regulatory tools available for managing urban development in

industrialized countries are not necessarily appropriate in many

southern and transitional countries. Where the rule of law leaves a lot

to be desired, where property rights are not strictly enforced, where

land registration and cadastre are incomplete, where

officially-sanctioned city plans are rarely available or taken

seriously, where much land subdivision and construction happen without

permits, where enforcement is intermittent and often corrupt, and where

a large part of the citizenry cannot afford minimum standard shelter,

new approaches are needed. The large majority of urban authorities in

developing countries do not in consequence often engage in realistic

minimal preparations for growth. It is essential to secure the necessary

public lands and public rights-of-way necessary to serve future urban

growth, protect sensitive lands from building, and invest in minimal

infrastructure—transport grids, water supply, or sewerage and drainage

networks—to accommodate growth that is coherent. Instead, the

authorities some-times focus on ambitious utopian master plans that are

never meant to guide development on the ground, take many years to

complete, and are usually shelved shortly after their publication. At

other times, they simply refuse even minimal planning and investment,

hoping against hope that their overcrowded cities will stop growing.

Even many plans developed with the assistance of donors have neither

been endorsed nor institutionalized. Needless to say, it is more

expensive to provide trunk urban infrastructure in built-up

areas—especially in areas developed by the informal sector—than to

provide such services, or at least to protect the right-of-way needed

for such services, before building takes place. The absence of even

minimal preparation for urban expansion–on both the activist and the

regulatory fronts–is, no doubt, an inefficient, inequitable and

unsustainable practice, imposing great economic and environmental costs

on societies that can ill afford them. For all of these (bad) examples

of urban expansion caused by sprawl and informal/illegal housing and

dwellings, modern concepts of sustainable management are urgently

needed.

The two known approaches in this field, the set-up of regulatory

measures on the one hand and the public initiatives on the other, are

commonly accepted but do not necessarily lead to success. Looking at the

initiatives approach it becomes clear that the need for sufficiently

consolidated property systems to gain long-term success is

underestimated. A formally correct situation without conflicting

property rights and disputed land titles remains a pre-condition not

only for enabling land and housing markets but also for public

initiatives in the sense of securing land for public needs assuring

sites and services. Sustainable land management (SLM) using urban

planning instruments and master plans can reasonably take place to

allocate zones or plots for trade, industry, and housing as well as for

public sites having a formally clear situation concerning property only.

To create good conditions for improving the property and planning

situation a solid legal base has to be put in place before further land

management activities are undertaken.

The key question remains: How can land management be implemented in a

dynamic envi-ronment taking into account economic development, the need

for increasing food and fiber production, as well as preserving

production capabilities and preventing land degradation? How to plan and

manage all uses of land in an integrated manner such that land

management becomes sustainable and supports wellbeing and good

governance? The following findings can be stated as assertions.

Statement 1: Economic development consumes land.

Statement 2: (Sub-)Urban development sprawls on agricultural land.

Statement 3: Land consumption and sprawl cannot be stopped but can be

guided and controlled.

Statement 4: Guidance of land consumption and SLM creates better

conditions for de-velopment.

Statement 5: SLM needs a cadastre as a pre-requisite.

Statement 6: Resolution of informal squatter area problems requires the

establishment of 'temporary development zones' with special legal

provisions.

2. STATEMENT 1: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CONSUMES LAND

As a basic rule it must be accepted that economic growth leads to the

demand for land. This happens in agricultural-based as well as

industrial economies. By 2009 economic growth in Switzerland resulted in

one square metre of land (agricultural ~) being consumed by streets and

buildings every second. With a well defined and permanently monitored

land use plan-ning system in place the consumption of land could not be

hampered. Several towns had to integrate formerly independent villages

as suburbs. Equal results can be found in the megacity of Baku,

Azerbaijan, and Accra, Ghana. There developments combined with migration

from the land produced a phenomenal construction boom (Figure 2-1).

Figure

2-1 Construction activity in Azerbaijan (2008, left) and Ghana, Accra

(2011, right).

3. STATEMENT 2: (SUB-)URBAN DEVELOPMENT SPRAWLS ON AGRICULTURAL LAND

On all continents, a relative decline in average urban growth rates has

been observed for the last 20 or 30 years, compared to those of the

preceding decades. This declining trend in demographic growth becomes

more obvious if fixed perimeters are used, as a general process of

spatial expansion is being seen everywhere. The advancement of urban

sprawl along communication routes often precedes the type of sprawl

where the empty areas are filled.

Aside from these general forms of urban sprawl, the patterns of

peripheral expansion turn out to be varied in terms of type of housing

conditions, population pattern, means of protecting structures,

construction, and social categories. Despite geographical,

socio-cultural and political situations differing greatly from one

metropolitan area to another, the processes of urban expansion are

similar.

In metropolitan areas of developing or post-conflict countries, the

informal urbanization of the outskirts is a classic working-class

practice. This happens in the form of clandestine housing developments

that fail to comply with the planning regulations, or in the form of

illegal occupation of sites without the owners’ consent, with

inhabitants constructing their own, often precarious, dwellings. This

illegal occupation (e.g. Kosovo (UNCESCR 2008), invasiones in Latin

America, squats or squatter settlements in Asia, campements in Africa,

urbanisation sauvage in Haiti) develops preferentially on available

sites on the city’s outskirts, often un-suitable for habitation. It may

equally occur within gaps in the urban area, including in central or

pericentral zones.

Figure

3-1 Sprawl as a planned development for IDP’s Gardabani near Gori,

Georgia (left) or Gihembe IDP camp, Rwanda (right).

Sprawl may also result from planned development, as demonstrated by

detached housing developments and other residential programs produced by

the capital investment sector or con-trolled by the public sector. Some

projects may be on a very large scale: new districts corresponding to

satellite sub-cities in Delhi, huge metropolitan projects in Bangkok,

edge cities in Cairo, resettlements of IDP’s in Ramana (Baku,

Azerbaijan), Gardabani (Gori, Georgia, Fig-ure 3-1), or Gihembe (Rwanda,

Figure 3-1), etc.

4. STATEMENT 3: LAND CONSUMPTION AND SPRAWL CANNOT BE STOPPED BUT CAN BE

GUIDED AND CONTROLLED

The sustainable treatment of land as a finite resource today is a mayor

goal of space-oriented activities. Against the background and the

requirements of a growing population, the World Bank (2006) defined its

SLM as a knowledge-based procedure that helps integrate land, water,

biodiversity, and environmental management to meet rising food and fiber

demands. This should be achieved through sustaining ecosystem services1

and livelihoods. This definition is focused mainly on agriculture and

rural development. When it comes to urbanized areas the water,

environmental, and biodiversity aspects may take priority.

Bearing in mind Prud’homme et al. (2004) the city itself, based on its

economic role as a fly-wheel, is the moving force for sprawl. The

pressure to repopulate or manage the outskirts problems by legally

approved zoning is mainly dependant on sanitation needs and economic

reasons, as mentioned above. These processes are guided by risk-based

land use planning or prioritized public interest. In non-industrial

countries economic pressure often is overwhelm-ing and dynamic so even

guidance and control do not happen if the relevant instruments are not

in place (UN Habitat 2010). Land consumption, however, declines right

away if the econ-omy shows signs of weakness.

Direction is successful especially if there is danger to be avoided by

risk-based land use planning measures. Hazardous areas such as

floodplains, mud/land and snow slide areas, etc. (Figure 4-1), are not

suitable conditions for housing (Kohli, A. 1999). Even belated

identification can be the reason for resettlement or restricted areas.

In such cases active land use planning becomes SLM and is an asset for

the community by increasing security of life and of investments as well

(Kohli, A., et al. 2001).

1Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems.

These include: - Provisioning services that provide necessities such as

food, water, timber, and fiber; - Regulating services that affect

climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; - Cultural services

that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits; -

Supporting services such as soil for-mation, photosynthesis, and

nutrient cycling (UNEP 2005).

|

|

Figure

4-1 Debris flow in the Bernese Alps, municipality of Brienz (2005,

left), Switzerland and dwellers settle-ment in Port-au-Prince built on a

landslide prone area, Haiti (2010, right, Photo © Ä. Forsman, UN

Habitat).

5. STATEMENT 4: GUIDANCE OF LAND CONSUMPTION AND SLM CREATES BETTER

CONDITIONS FOR DEVELOPMENT

By applying strong SLM procedures, including transparent land

consolidation methods to rural and urbanized areas, amongst other

things, investments in utilities become highly worthwhile and create

more favorable effects than in sprawled areas. Efficiency rates increase

and network planning for water or sewage makes sense. Housing and

industrial site developments as well may profit from available and

easily connected utilities, as these effects can be realized by first

agglomerating construction in abandoned areas, industrial wasteland, or

gaps in settlements. A higher density of users creates better conditions

as overall costs for citizens and capital investors decrease and service

quality may increase.

In Azerbaijan, especially in Baku (Figure 5-1), continuing degradation

of the urban environment is going on due to the lack of a modern spatial

planning system, missing master plans, or absence of detailed plans for

urban areas. Consequently, new construction is carried out under the

pressure of market forces, basically without proper planning

regulations. Even forced eviction for town development is common. In

addition it is not quite clear who is responsible for the preparation of

plans and issuing of permissions for changes in land-use as well as for

building permits. State planning authorities still try to oversee

planning issues that might be handled at the regional or municipal level

(UNECE, Committee on Housing and Land Management 2007). Easy to apply

building permits would help to increase security of the property. Stable

and transparent procedures with defined planning horizons create

security amongst owners and a readiness for dynamic developments — all

factors for the well-being of a developing and an industrial community.

|

|

Figure

5-1 Urban construction projects in Baku, Azerbaijan (2008, left), and

urban development with evictions in Borei Keila, Cambodia (2012, right).

6. STATEMENT 5: SLM NEEDS A FAST APPROACH CADASTRE AS A PRE-REQUISITE

Land management needs (in land reform, land consolidation, land use

planning, etc.) as a pre-condition a sustainable base documentation of

topology, topography, and property ownership or tenure. In cases where a

reliable cadastre is missing, property issues remain unclear and SLM is

hampered (The World Bank 2009). So in the immediate aftermath of a

conflict the securing, restoration, or setup of land records is crucial.

The cadastre follows as a consequence of where land records are

available (Augustinus, C., et al. 2007). Bad examples are easy to find,

such as in Kosovo (Andersson, B., et. al. 2003) or other Balkan

countries. Even if a form of a cadastre system is in place but is

unreliable and poorly maintained an unclear property situation makes SLM

very difficult, as shown above in Azerbaijan.

Loss of property and investments because of a lack of transparency in

public planning and an unreliable cadastre will cause distrust in

cadastral documentation. Problems will be created by illegal development

and construction in restricted or endangered areas. Since 2007 in Kosovo

state and municipal authorities have tried to regularize and legalize

illegal constructions as a first step back to reliable land management

systems as the cadastre (UNCESCR 2008).

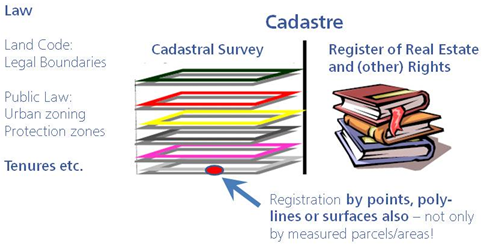

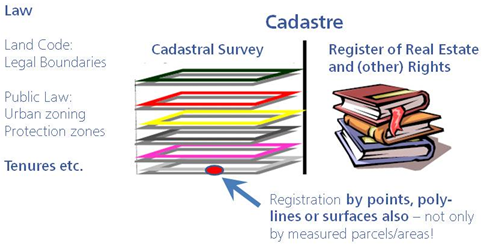

Recently the call for new tools has been heard. FIG is starting new

initiatives as manifested in the publication Social Tenure Domain Model

(STDM) (Lemmen, Chr. 2010). Unfortunately the data model achieved under

this initiative is even more complicated than others. A more promising

solution is the simplified application of the Cadastre 2014 approach

concentrating on the registration of independent topics for the actual

state of tenures, properties or holdings (Figure 6-1). No surveying is

required but only the identification of property or tenure based on

points, poly-lines, or surfaces is needed. Efforts can be focused on the

time consuming definition for regularization and legalization of

informal and illegal tenures.

Figure

6-1 Cadastre 2014 data model approach for easy and fast registration of

tenures and holdings besides legal boundaries.

Comprehensive documentation in maintained digital cadastres of the

actual existing legal situation of land following the principle of legal

independence stated by Cadastre 2014 (Kauf-mann, J., Steudler, D., 1998,

page 29, Figure 3.18) will form a strong basis for SLM. The procedure

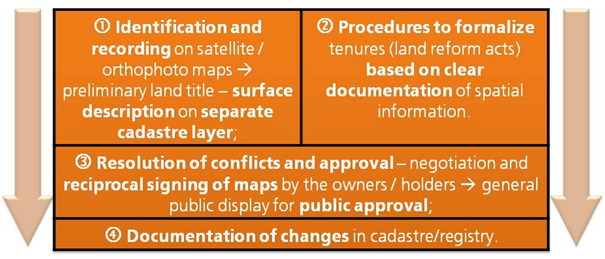

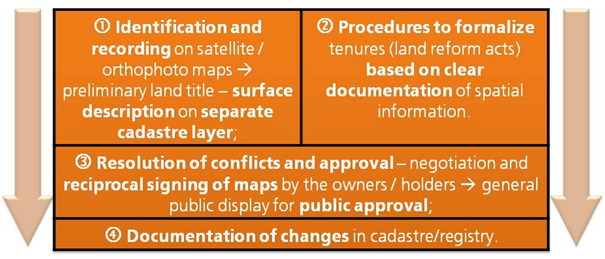

for fast approach cadastre documentation (Figure 6-2) shall be defined

as follows:

| Step 1: |

Identification of property, house, or tenure on

satellite or ortho-photo maps as point objects to create a

preliminary land title. Definition of a surface description on a

separate cadastre layer in the GIS by poly-lines accepting

overlapping claims, rights, and disputes. The latter shall have

a topological link to the point object forming the land title.

The cadastre information ob-tained in such a way shall reflect

the actual situation should it be legally approved or based on

customary possession. It serves as a working base and needs

stepwise improvement. |

| Step 2: |

Definition of procedures to formalize tenures

based on clear documentation of spatial information. The

procedures have to end up in a legally approved situation. |

| Step 3: |

Further steps focus on the resolution of

conflicts and approval of the property and tenure situation

reflected by the cadastre. As a very easy and effective

procedure the negotiation and reciprocal signing of

(ortho-)photo maps by the owners or holders shall be used. After

this a general public display of the resulting cadastral

documentation may lead to public approval. |

| Step 4: |

Having clear documentation of the actual

situation in the cadastre, the communal and state driven

processes of formalization of ownership or holdings can start by

legally approved land reform acts. |

Figure

6-2 Fast Approach Cadastre Documentation to achieve basis for resolving

pending land conflicts.

7. STATEMENT 6: ESTABLISHMENT OF 'TEMPORARY DEVELOPMENT ZONES' TO

RESOLVE SQUATTER PROBLEMS

To overcome the dodgy situation of sprawl combined with informal/illegal

housing and dwellings, a joint approach of land consolidation and urban

planning under special right is recommended. This concept asks for the

initialization of a legal framework dedicated to the development task as

an initial step applying to a separate perimeter of action–so called

'temporary development zones'. From several experiences we learnt that

the adjustment of the legal framework has to take place before any

action of master- and urban-planning, land rights documentation

(cadastre) or regularization action is started. In doing so the

regulations by existing law concerning several fields as civil code,

real estate registration law, cadastre law, land use law, land reform

and privatization law, etc., are arranged and completed to a rule set

(Table 7-1) adapted to the development task under a Governmental Decree

on the Establishment of Temporary Development Zones (TDZ). This rule set

overrides the existing laws mentioned above in specific aspects.

Table 7-1 Legal aspects to be ruled for Temporary Development Zones.

| Civil Code, Real Estate

Registration Law, Cadastre Law: |

Changes to land parcels as well as to rights

(encumbrances) are applicable within TDZ and are registered free

of charge to the new owners. Compensa-tion by the TDZ project.

|

| Land Use Law: |

The land use within TDZ can be changed as

technically accountable. |

| Land Reform Law, Privatization Law: |

Land allocations may be freely changed within

TDZ. |

| Expropriation Law: |

Land expropriation against appropriate

compensation is applicable within TDZ. |

| Building Law: |

New constructions are permitted and registered

free of charge to the new owners. Compensation by the TDZ

project. |

| Public Services Law: |

Public utilities are forced to provide services

and metering to TDZ under appropriate conditions. |

Taking the pre-conditions into account the following process is to be

implemented:

| Step 1: |

Definition of the perimeter of action (dwelling area to be

developed) includ-ing sufficient compensation in adjacent area

or in the near surroundings. |

| Step 2: |

Common agreement and decision on TDZ: The assembly of

stakeholders and local government shall make a decision on the

establishment of special rights for TDZ based on the

Governmental Decree on the Establishment of Temporary

Development Zones (TDZ) for a defined project period. |

| Step 3: |

TDZ Project Analysis Phase: Documentation of formal/informal

land rights, and public demand (services, rights-of-way,

sensitive and endangered lands). |

| Step 4: |

TDZ Project Land Management Phase: Redistribution plan

according to agreed rules of real-substitution and compensation |

| Step 5: |

Public Display of the allocation plan with the right of

administrative appeal for unsatisfied former owners |

| Step 5: |

Registration of new ownership; payments of compensation.

|

| Step 6: |

Reconstruction of settlements by private and utilities by

public entities. |

In running projects, e.g., in Kosovo (Government of the Republic of

Kosovo, MPS 2008) and Azerbaijan, critical factors for success (Kohli,

A. 2004) were identified to be:

-

Documentation of informal/illegal occupation and

construction before regularization;

-

Regularization of informal/illegal occupation

under formal and appropriate compensation to former owners;

-

Management of land and resources according to a

concept developed under the aspects of sustainability;

-

Compulsory land acquisition by the

public–eventually financed by the Bank–in case a direct role in land

development is justifiable (e.g., services, right-of-way) (The World

Bank 2009);

-

Force local government to take an active role

within a very short time; the legal provisions for temporary

development zones shall expire after a limited period;

-

Easy and free of charge registration for new

ownership and building under concurrent compensation for

registration by the TDZ project.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The logical consequence of economic development—the

inevitable consumption of land—substantiates the need for sustainable

land management and cadastre. Successful attempts to direct or manage

land consumption or land use can only be accomplished with the solid

base of a well-maintained digital cadastre following the Cadastre 2014

principles, which represent the actual situation of property and tenure

holdings (fast approach cadastre). The flexibility of handling not only

legally approved but also informal and temporary objects through the use

of the independent layer technology leads to an easy adjustment of

documentation systems to meet the needs for the resolution of land

problems. The sustainable resolution in terms of SLM for squatter and

occupation problems asks for joint approaches of land consolidation and

urban planning under special right. The instrument of 'TEMPORARY

DEVELOPMENT ZONES' is based on a rule set adapted to the development

task under Governmental Decree overruling the relevant land related

laws. This enables a combined implementation of regularization of

informal/illegal property situations and considerable improvements of

services as well as sound legal protection of housing. However, the

approach presented can only work if the Governmental Decree is put in

force before project implementation will happen and the government

allocates substantial funds for compensation.

REFERENCES

Andersson, B., Meha, M. 2003, Land Administration in

Kosovo – Practice in Cooperation and Coordination, UN/ECE-WPLA and FIG

Com3 & Com7 Workshop on Spatial Infor-mation Management (SIM) for

Sustainable Real Estate Market 2003, Athens, Greece.

Augustinus, C., Lewis, D., Leckie, S. 2007, A

Post-Conflict Land Administration and Peace-Building Handbook, Series 1,

UN-HABITAT, http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/get

ElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=2443&alt=1

Government of the Republic of Kosovo, Ministry of

Public Services 2008, Summary of Find-ings of the KCA Functional Review,

Functional Review and Institutional Design of Minis-tries (FRIDOM)

Project, Pristina, Kosovo.

Kaufmann, J., Steudler, D. with Working Group 7.1 FIG

Commission 7 1998, Cadastre 2014, A Vision for A Future Cadastral

System, FIG Booklet, http://www.swisstopo.ch/fig-wg71/cad2014.htm.

Kohli, A. 1999, Measures to Prevent Scouring of Structures in

Floodplains, Wasser & Boden, 51/3, 40-45 (in German).

Kohli, A. 2004, Reconstruction of a GIS-Cadastre in a

developing Country, GeoSpatial World 2004 Congress, INTERGRAPH, Miami

Beach, Florida, USA.

Kohli, A., Hager, W.H. 2001, Building Scour in

Floodplains, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Water

and Maritime Engineering 148, Issue 2, 61-80.

Lemmen, Chr. 2010, The Social Tenure Domain Model – A

Pro-Poor Land Tool, FIG – GLTN – UN-HABITAT, International Federation of

Surveyors (FIG) Copenhagen, Den-mark.

Prud'homme, R., Dupuy, G. and Boret, D. 2004, The New

Constraints of Urban Development, Institut Veolia Environnement, Report

n°1, Paris, France.

The World Bank 2006, Sustainable Land Management -

Challenges, Opportunities, and Trade-offs, Washington, USA

The World Bank 2009, Systems of Cities, Harnessing

urbanization for growth and poverty alleviation - The World Bank Urban

and Local Government Strategy, Washington, USA

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UNCESCR) 2008,

Property Return and Restitution: Kosovo,

http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/info-ngos/COHREUNMIK.pdf

UNECE-Committee on Housing and Land Management 2007,

Land Administration Review: Azerbaijan, Programme of Work 2008-2009,

Geneva, Switzerland.

UNEP 2005, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment,

Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Gen-eral Synthesis Report,

http://www.unep.org/maweb/en/synthesis.aspx

UN-HABITAT 2010, Strategic Citywide Spatial Planning:

A situational analysis of metro-politan Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Summary

Report, Nairobi, Kenya.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr. Alexander Kohli, born in 1967, graduated

from the Department for Rural Engineering and Surveying in 1995 at the

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich). From 1995 until 1998

he was doing his PhD studies at the Versuchsanstalt für Wasserbau (VAW),

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) on BUILDING SCOUR IN

FLOOD PLAINS.

After the PhD in 1998, in 1999 he earned the Swiss

license for licensed land surveyors. With BSB + Partner he runs a

special department for Consulting and Development working for public

(World Bank, EBRD, Swiss Government) and private organizations in the

fields of Project Development, Land Management, Administration and

Cadastre worldwide.

In 2009 Dr. Alexander Kohli was dispatched as the

delegate of the Swiss professional organi-zation of surveyors in FIG to

Commission 8, Spatial Planning and Development. Since 2012 Dr. Kohli

acts as Vice-President of the SWISS LAND MANAGEMENT foundation.

CONTACTS

Dr. Alexander Kohli, Vice-President

SWISS LAND MANAGEMENT

c/o BSB + Partner, Ingenieure und Planer

Leutholdstrasse 4

CH-4562 Biberist, Solothurn

SWITZERLAND

Email:

alexander.kohli@bsb-partner.ch

Web site: www.swisslm.ch

|