Implementation of Marine Cadastre in Israel

Haim SREBRO, Israel

|

Haim Srebro

|

1)

This paper was presented at the FIG Working Week in Sofia, Bulgaria,

17-21 May 2015. Implementation of marine cadastre in Israel started in

2011. This paper elaborates on the implementation and plans

regarding a marine cadastre that will achieve a cadastral coverage over

the sovereign area of Israel, including a description of its

implementation in the approved marine settlement blocks as a result of

cooperation between Survey of Israel (SOI) and the Department of Registration and Land

Settlement (The Land Registry) under the Ministry of Justice.

SUMMARY

The first three marine settlement block plans, designated as marine

cadastre in Israel, were approved and signed as registered blocks in

October 2011. This was the first milestone of implementing a marine

cadastre in Israel following and concluding preparatory work for a few

years. Since then, an additional 13 marine blocks have been fully

registered and 13 are in an advanced stage before their final approval.

This reflects a fast growing interest and various activities regarding

the coastal and marine environment in Israel.

Israel is a coastal state. The marine areas of Israel in the

Mediterranean Sea include the territorial sea (TS) where it has full

sovereignty and the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) where it has partial

sovereign rights. In recent years the Survey of Israel (SOI) launched a

few relevant initiatives, including the following: coordinate based

cadastre (CBC) projects, one of which included transformation of 60 land

registration blocks to CBC along the coast line, 3D cadastre, and

land-marine Spatial Data Infrastructure. SOI published a series of

hydrographic charts and two atlases showing the formal coast lines to

support the Law of Protection of the Coastal Environment.

The rapidly developing activities regarding the search for gas and

oil in the above-mentioned Israeli marine areas, and the important gas

explorations, including the activities of developing a marine

infrastructure for the conduction and distribution of the exploited gas,

under the responsibility of the Ministry of Energy and Water, play an

important role in the development of the marine area. In addition, other

ministries advanced development plans in the marine area, including the

Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of

Transportation, among others.

These requirements were considered before launching the marine

cadastre initiative.

The final settlement of a marine cadastre depends on the final

delimitation of maritime boundaries between Israel and its neighbors. As

long as these boundaries are not concluded and agreed upon, the block

plans may cover the marine area except for the marginal blocks that

border the international maritime boundaries. In December 2010 Israel

and Cyprus agreed on the delimitation of their maritime boundary in the

EEZ.

This article elaborates on the above-mentioned situation and plans

regarding a marine cadastre that will achieve a cadastral coverage over

the sovereign area of Israel, including a description of its

implementation in the approved marine settlement blocks as a result of

cooperation between SOI and the Department of Registration and Land

Settlement (The Land Registry) under the Ministry of Justice.

1. INTRODUCTION

Israel is a maritime state that connects between the Mediterranean

Sea and the Red Sea. In addition, Israel shares the Dead Sea and

contains the Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) as an internal lake.

The traditional cadastre, since the beginning of the cadastral

surveys by the British authorities in the 1920s, referred only to a land

cadastre. This trend continued after the independence of the State of

Israel in 1948. Today, the land settlement covers 96% of the land area

of Israel. Most of the unsettled land areas are situated in the northern

part of the Negev (the South of Israel). The current rate of growth of

the population of Israel is very fast, probably the fastest in the

western world. This is reflected by fast urbanization, reducing the open

and green areas, as well as by utilization of the space above and

beneath the ground. This trend is an important reason for the initiative

of implementing a spatial cadastre (3D cadastre) in Israel (Shoshany et

al., 2004). Following a significant upgrade of technology at the Land

Registry, SOI and the Land Registry will hopefully push the 3D cadastre

forward.

Another phenomenon characterizing the rapid population growth and the

fast urbanization is the exploitation of the coastal areas. One of the

measures taken to protect the coastal area is the Law of Protection of

the Coastal Environment, the reference coast line for which in the

Mediterranean Sea was defined by the Director General (DG) of SOI

(Srebro, 2008) and afterwards in the Red Sea and the Kinneret in 2011.

In addition, there are rapid developments and activities in the sea

itself including the enlargement of ports, the construction of new

marinas, power stations, cables for communication, the licensing of gas

and oil drillings, etc.

In addition, there is a growing trend to construct part of the

infrastructure along the coast and in the sea, including a network of

gas pipes. This construction, under the responsibility of the Ministry

of Energy and Water, is augmented by the exploration of new large gas

fields in the sea opposite the Israeli coastline. The Ministry of

Agriculture promotes marine agriculture in Israeli waters. Long-range

planning takes into account the potential construction of artificial

islands, as well as an airport and roads in the Mediterranean Sea

opposite the coast.

A few years ago, following an initiative involving the transition to

a Coordinate Based Cadastre (Srebro, 2010), which included a pilot

project of block plans along the coast line, the DG of SOI decided to

begin activities towards establishing a marine cadastre as a

continuation of the land cadastre seawards.

2. MARINE CADASTRE

2.1 The scope of a marine cadastre

The definition of the term marine cadastre has two interpretations

that follow different scopes and concepts (Binns et al., 2003).

One reference to marine cadastre is similar to the land cadastre,

referring to boundaries: A marine cadastre is a system that enables the

boundaries of maritime rights and interests to be recorded, spatially

managed, and physically defined in relationship to the boundaries of

other neighboring or underlying rights and interests (Robertson et al.,

1999).

The other definition covers a wider scope: A marine information

system, encompassing both the nature and spatial extent of the interests

and property rights, with respect to ownership, various rights and

responsibilities in the marine jurisdiction (Nichols et al., 2000).

Furthermore, the concept of marine cadastre is developed later on to

the scope of the Multipurpose Marine Cadastre in the USA by NOAA Coastal

Services Center and the Mineral Management Service (MMS), as shown in

their homepage (www.csc.noaa.gov/mmc)

and by the FGDC Marine Boundary Working Group.

The US Maritime Cadastre is an information system that supplies web

services, based on authoritative data sources, integrating legal,

physical, ecological, and cultural data and information in a common GIS,

as well as rights, restrictions, and responsibilities (Fulmer, 2007).

The Canadian approach also refers to the multipurpose nature of the

marine cadastre and supports it by a marine geospatial data

infrastructure as part of the Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure

(Sutherland, 2003).

This trend was also adopted by the International Hydrographic

Organization, which decided in 2007 to establish a Marine Spatial Data

Infrastructure Working Group (MSDIWG) and prepared in 2009 a guidance

publication for Hydrographic Offices (IHO Publication C-17 – Edition

1.1.0 February 2011) regarding the marine dimension of National Spatial

Data Infrastructure (NSDI).

The Israeli approach until now, as practiced in the Sea of Galilee,

the Dead Sea, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea is to adopt the

limited scope of a marine cadastre, referring to the boundaries of

property rights and the rights of use to be registered. Thus, the marine

cadastre in Israel is actually a natural continuation of the land

cadastre; it follows the same principles and methods of implementation.

In parallel, SOI launched an initiative to build a marine GIS and the

DG of the Survey, who chairs the Inter Ministerial Committee for GIS,

declared in November 2011 the establishment of a sub-committee for

marine SDI.

In addition, an agreement on the delimitation of the EEZ was signed

between Israel and Cyprus in December 2010.

2.2. The marine areas

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (United Nations, 1983)

(Hereinafter: The Convention) supplies a general reference regarding the

sovereignty and rights of a state in the sea. The Convention defines a

few relevant maritime zones with reference to these rights:

Internal waters of a State include waters between the actual

coastline and straight baselines along the coasts. A State has full

sovereignty in internal waters and its rights over internal waters are

identical to its rights over the land area. In cases where internal

waters from the baselines landwards are established there is a right of

innocent passage (The Convention, Article 8).

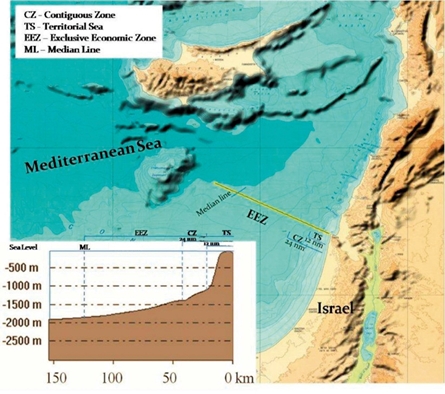

The breadth of the territorial sea (TS) of a State covers the area

between the baselines along the coasts and a limit line not exceeding 12

nautical miles (NM) is measured from the baselines (The Convention,

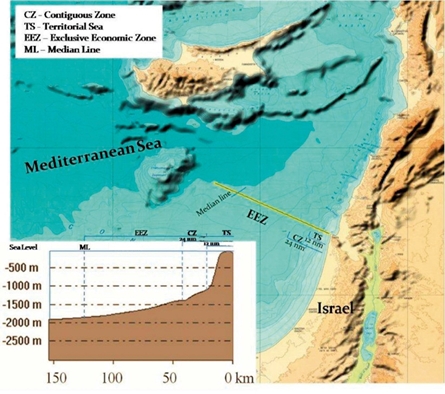

Article 3) (see figures 1 and 2).

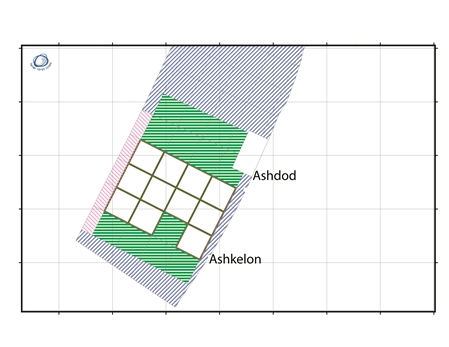

Figure 1: The maritime zones of Israel in the Mediterranean Sea (A

general approximated scheme. Background: Admiralty Chart 183)

Figure 2: A Profile along the Israeli maritime zones in the

Mediterranean Sea

A State has full sovereignty over its territorial sea including the

air space over the territorial sea and the subsoil (The Convention,

Article 2). Vessels of other States have rights to innocent passage in

the territorial sea of a State (The Convention, Article 17).

The contiguous zone is up to 24 NM (12 NM beyond the TS) from the

baselines (The Convention, Article 33). The rights of the State in this

area do not refer to sovereignty but instead to the prevention and

punishment of infringement of customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary

laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea.

The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of a State is up to 200 NM from the

coastal baselines (The Convention, Article 57), beyond which are the

high seas. The rights of a State in this area refer to living resources

like fishing. In addition, there are specific rights for mineral

resources and to exploitation of the seabed and sub-surface, which refer

to the continental shelf (CS) which may exceed the EEZ under specific

conditions in the open sea. There are rights of freedom of navigation as

well as flight rights over the EEZ. A State has only limited sovereignty

rights over the EEZ to use specific resources (The Convention, Article

56).

Other zones, which are specified in The Convention beyond 200 NM, for

example, with reference to the Legal Continental Shelf and other areas

(see also Nichols, 2003), are not relevant to Israel because in the case

of the State of Israel the EEZ is less than 200 NM. Thus, the State of

Israel has both rights to living resources (referring to the EEZ) and

rights to non-living resources (referring to the continental shelf) in

its EEZ.

Various types of rights are dealt with regarding the maritime zones

including navigation rights, customary rights, public access rights,

fishing rights, riparian rights, development rights, mineral resources

rights and seabed use rights (Sutherland, 2009).

The application of The Convention in Israeli waters: Israel is not a

party to The Convention, but views the majority of its provisions as

customary law.

2.3 The requirements for a marine cadastre

The first question that we have to refer to is: Why do we need a

marine cadastre?

The answer is the same as for the land cadastre. It is required in

order to settle ownership rights and rights of use. The Israeli cadastre

does not stop at the coast line. The more the marine space is utilized,

the more the settlement of these rights is and will be required. Since

the rights are attached to a specific space, an accurate definition of

this space is important. Owing to the lack of geographic features on the

surface of the sea, the proper way to define it is to define the

geographic spaces by coordinates. The recommended method of delimitation

and registration of rights is by implementing a coordinate-based marine

cadastre. This is also a preliminary answer to the question, how can a

marine cadastre be implemented.

The marine cadastre should support the State and the regionally

driven marine spatial planning initiatives regarding fishery,

transportation, recreation, energy production from wind and wave use,

marine agriculture, communication cables, oil and gas permits and

drillings, installations and pipelines, protection of marine ecosystems,

etc., encompassing both property rights and rights of use. Marine

boundaries are not demarcated but delimited by coordinates. Such

delimitation should prevent confusion, disagreement and conflicts.

In envisaging future development and requirements, 3D registration is

required to enable the management of rights on the sea surface, in the

water space, and in the subsoil space. This should also cover

archeological sites in the marine space.

The second question that we must refer to regarding the application

of a marine cadastre is: to which area should the marine cadastre apply?

A few government agencies are responsible for answering this

question. The ownership of State lands in Israel is under the Israeli

Land Authority. The registration of lands is under the responsibility of

the Land Registry in the Ministry of Justice and the responsibility for

the delimitation of lands for registration, as well as the delimitation

of the international borders of Israel, lies with SOI. The Ministry of

Foreign Affairs has its relevant responsibility for the international

borders of the State. Thus, the final decision regarding the

registration in the sea will be a result of cooperation and consultation

between a few Government offices. The decision of the DG of SOI

regarding this question was to begin technical preparations for a marine

cadastre as preliminary work for the final marine cadastre. According to

his view, in coordination with the view of the Director of the Land

Registry, the first priority should refer to the areas that are under

full sovereignty of the State. This should be the area over which a

marine cadastre would be applied first. This decision is based on the

relevance of the cadastre to ownership and development rights. Ownership

rights in a State are covered by its rules which are applicable to its

sovereign areas. These areas refer to the land area, the internal waters

and the territorial sea of the State. In the future, the question of

applying a marine cadastre in the Israeli EEZ should be dealt with,

since there are limited sovereign rights in this area. In practice, the

current main task in the EEZ is to delimit concession areas and to

manage and control permits and rights to drill and exploit minerals.

Following the experience of the USA, Canada and Australia, the

Israeli Marine Cadastre should definitely be applied to the Israeli EEZ

in the Mediterranean Sea, though it refers to limited rights. This

approach requires preparing an Israeli marine spatial data

infrastructure that should cover marine areas to the full extent of the

Israeli EEZ. Following this approach it is only a matter of

priority to apply the marine cadastre at first only to the Israeli

territorial sea area.

However, the legal method of registration of land settlement blocks

is followed, since Israeli law in general is currently not applicable to

the EEZ, and the current possibility to register marine settlement block

plans refers only to the territorial sea area.

Taking into account the multilayered marine space on the sea surface,

above it, and below it, the answer to the question "where", should

include the three-dimensional space down to the depth of the subsoil.

The third question is: When should a marine cadastre be implemented?

The answer is: as soon as possible. This is justified by the low cost

and the high speed of the "land" settlement process when an area is

owned by the State and is still mostly free of rights of use, and is

characterized by low density of man-made features. The planned

activities and the continuous process of development and exploitation of

land along the coast, which is also reflected in the fast growing value

of lands along the coast, indicate that in the future the creation of a

marine cadastre will be much more costly and will take much more time

due to the construction of various installations and utilities.

This answer has already been validated for the last four years by the

accelerated activities of the Ministries and Municipalities in the

marine area.

2.4 Practical analysis of the implementation of marine cadastre in

Israel

As already indicated, Israeli waters include four areas: the

Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Dead Sea, and the Sea of Galilee.

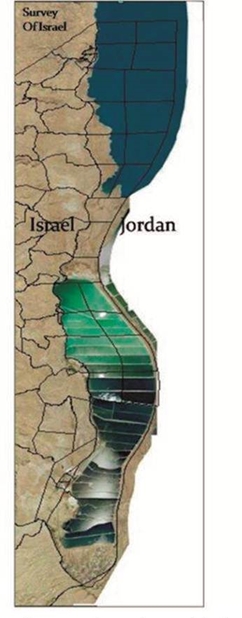

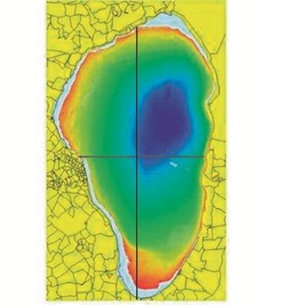

The Sea of Galilee is a lake within Israel. It already went through a

regular land settlement process, and was divided into 4 blocks as seen

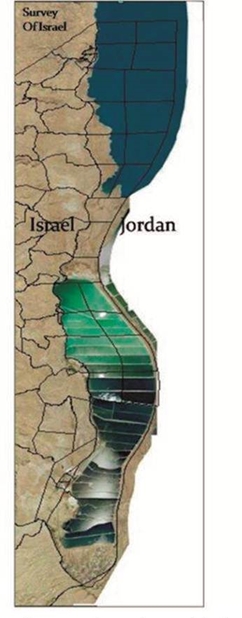

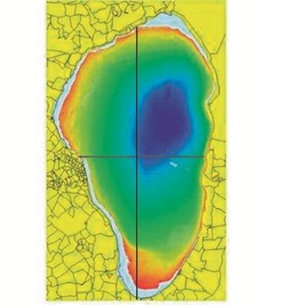

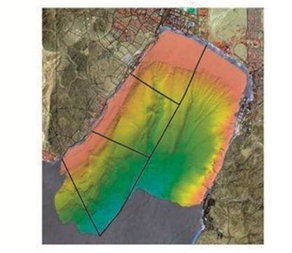

in figure 3.

This lake is considered as a land area and is not covered by The

Convention. Furthermore, due to the temporary lowering of the water

level of the lake, its outer strip has already partially dried, and each

of the four blocks consists today of both a water and land area.

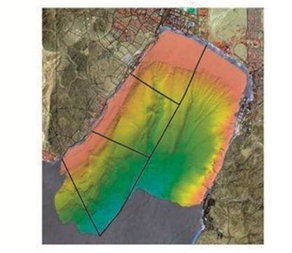

The northern part of the Dead Sea is divided by an international

boundary following the October 26, 1994 Treaty of Peace between Israel

and Jordan (Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty, 1994). The historical southern

part of the Dead Sea, has contracted and dried and is practically a

basin used for salt pans on each side of the international boundary

between Israel and Jordan (see figure 4).

Figure 4: The settlement blocks in the

Dead Sea and Salt Pans |

Figure 3: The land settlement blocks in the

Kinneret |

Figure 5: The land settlement blocks in the Red Sea |

Figures 3 and 5* make use of data from the National Bathymetry

Project.

(* Sade A.R., Hall J.K., Tibor G. et al (GIS Report GIS/03/2008) IOLR

Report IOLR/08/2008)

The Israeli Salt Pans' area is considered and dealt with to-day as a

land area. The Israeli waters of the Dead Sea are actually internal

waters. The land settlement in this area is dealt with like a land

settlement over the land area. The limits of the block plans in this

area, which are currently undergoing a land settlement process up to the

international boundary, are defined by coordinates, so it can be

considered as a practical (and not yet a legal) coordinate- based

cadastre.

The Israeli waters in the Gulf of Eilat - which is a branch of the

Red Sea also called the Gulf of Aqaba - are considered a territorial

sea. They lie between the coastline and the maritime boundary between

Israel and Jordan, which was concluded in 1996 following the 1994 Treaty

of Peace (Israeli-Jordanian Maritime Boundary Agreement, 1996). The

southern limit of this area has not yet been defined because Israel and

Egypt have not yet agreed on a maritime boundary in this gulf, but

following Article 15 of The Convention it should be delimited along the

equidistance line going from the terminus of the land boundary at Taba

(Srebro, 2009) up to the median line along the Gulf of Eilat. Since all

the Israeli waters in the Red Sea are considered territorial sea under

Israeli sovereignty, a marine cadastre in this area is applicable.

Actually, most of the area has already been settled as an extension of

the land cadastre (see figure 5).

2.5 Parallel relevant activities at the Survey of Israel

The basic definition of a marine cadastre includes the delimitation

of the cadastral blocks. Since the delimitation refers mainly to

coordinates on the water surface, the number of physical features that

are included in the block plans will be very limited, if any. But, since

the relevance of the cadastral delimitation, beyond the cases of special

installations and potential artificial islands, is to the multilayered

marine space, including the seabed and the subsoil, a proper mapping of

the seabed, including physical features in the relevant area, is an

important contribution to the cadastral division and to its application.

At present, most of the blocks will have no such information. The

blocks that will include some features will be the first line of blocks

that are near the coast and a few blocks where gas or oil drilling sites

plus transportation pipes or infrastructure cables that may exist as

well as fish growing sea farms.

Two other relevant activities are carried out during the last years

by SOI. One is the production of a series of hydrographic charts. SOI

has prepared 10 hydrographic charts covering the Israeli Territorial Sea

in the Mediterranean Sea. This includes one 1:250,000 chart, three

1:100,000 charts and seven large scale charts, in the framework of

cooperation with the Ministry of Transportation for the purpose of

safety of navigation. These charts contain a lot of data in the marine

area that can support a marine cadastre. The source data are collected

by the Survey of Israel, the Geological Survey of Israel, and the Israel

Oceanographic & Limnological Institute. An additional hydrographic chart

is being prepared for the Gulf of Eilat.

Another activity refers to the National Bathymetric Project, which is

run by a few agencies including the Geological Survey of Israel, the

Israel Oceanographic & Limnological Institute, the Survey of Israel and

others.

As analyzed by Ng'ang'a et al. (2003), bathymetry may play a

significant role in marine cadastre. This refers to the wide scope of

marine cadastre, including the safety of navigation, laying

communication cables, exploring and drilling for offshore oil and gas,

the location of underwater mineral deposits, and gaining an

understanding of the geological processes. It has a potential that has

not yet been implemented, which can be used in combination with other

geographic information to support marine boundary delimitation and

property rights. Bathymetry mapping is presented in this article in

figures 3 to 5.

In addition, when the use of mineral resources on the seabed and in

the subsoil develops, or when construction of special marine projects,

like artificial islands, develops, the need for implementing 3D or a

multi-dimensional cadastre will increase.

This requires the implementation of a CBC in the marine areas.

Therefore, taking into account the present supporting technologies and

infrastructure at SOI, the definition of the Israeli marine cadastre

should be based on coordinates.

This meets one of the present main initiatives at SOI, namely, to

transfer to a CBC. In addition, SOI has been promoting for a few years

an initiative of a 3D cadastre (Shoshany et al, 2004). This should be

integrated, when applied, into the marine cadastre wherever required.

The implementation of a CBC requires that all the boundaries of a

block be defined by coordinates (Srebro, 2010). A full definition of

blocks by coordinates in the sea is quite simple except for the case

near the limits of the marine areas of a state. This limitation refers

to the boundary between the marine area and the coastal area, in case

that such a boundary is not defined by dominating coordinates but

rather, by legal graphical documents. It also refers to the delimitation

of the territorial sea of a State and an adjacent State (usually an

equidistance line) and to the case of delimitation of the territorial

sea between a State and an opposite State (usually a median line).

3. THE MARINE AREAS OF ISRAEL IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

The cases of the Israeli marine areas in the Kinneret, the Dead Sea,

and the Red Sea have been described earlier and it was concluded that

the limits of the block plans in these areas should be transformed from

legal graphical documents to legal coordinates.

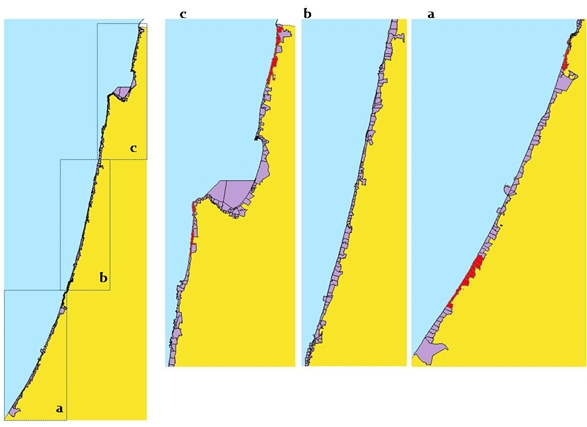

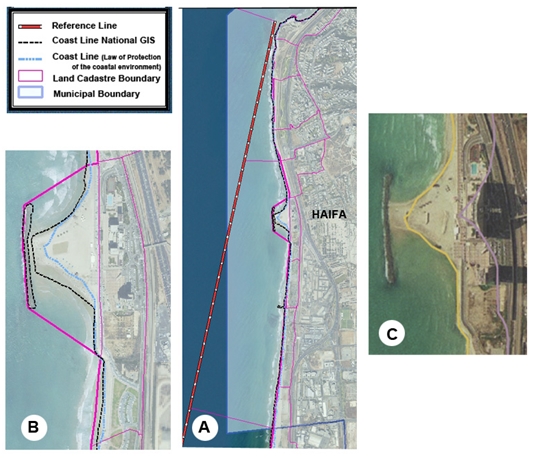

However, the case of the marine area along the coastline of the

Mediterranean Sea is more complicated. The length of the coastline is

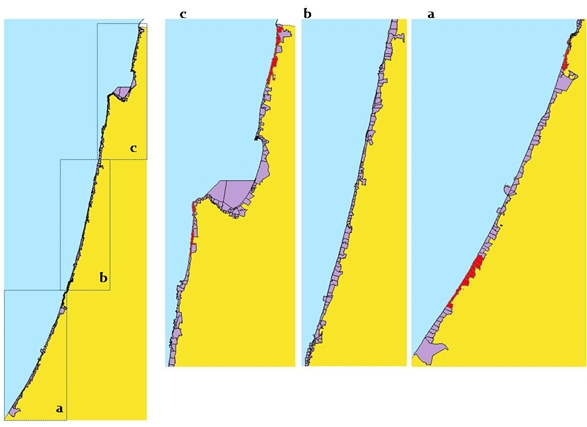

around 200km, along which exist 291 land settled block plans (see figure

6). The borders of 60 of these blocks have already been defined by

coordinates (Klebanov and Forrai, 2010).

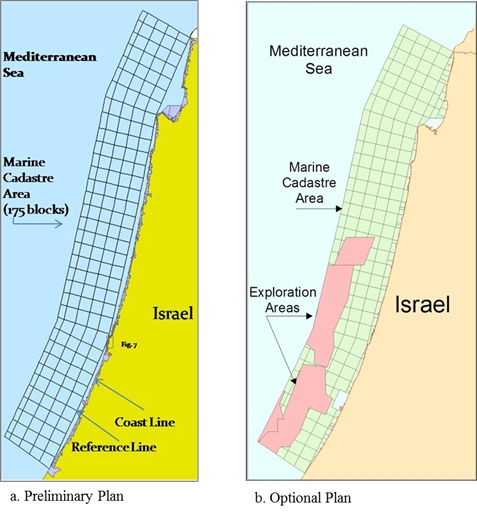

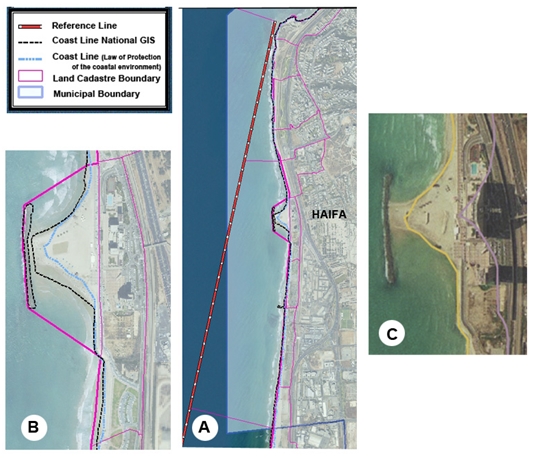

Figure 6 (a, b, c): Land blocks along the coast (In red: Coordinate

based Cadastre (CBC) blocks)

The Israeli TS in this area extends to a distance of 12 NM from the

base lines along the coastline. The EEZ of Israel in the Mediterranean

Sea cannot cover 200NM from the coast, because the distances between the

coasts of Israel and Cyprus, which are opposite coasts, are between

120NM and 200NM. Under customary international maritime law, the median

line between Israel and Cyprus, which is the outer limit of the Israeli

EEZ, is half way between the coastlines. As seen in figure 2, the

Israeli CS is included in the EEZ. In order to define a marine cadastre,

the TS should be sub-divided into block plans. The area close to the

coastline should be dealt with differently than the area that is more

distant, because most of the physical features and development in the

marine area are close to the coast. This refers to constructions like

ports, marinas, breakwaters, and pipelines. This area is also protected

by the law that protects coastal environments (Srebro, 2008).

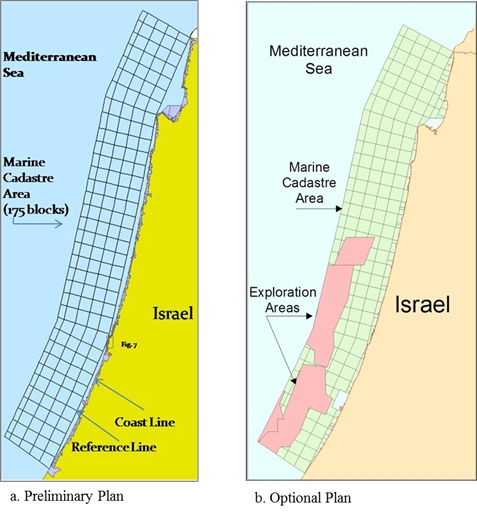

As a result, it was decided to limit the size of the adjacent blocks,

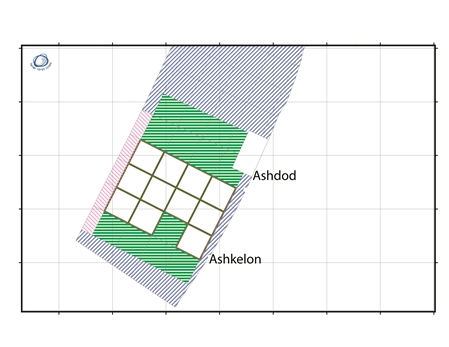

whereas the more distant ones were designed roughly to a size of 5x5km

(see figure 7a) following the preliminary guidelines of the land

settlement officer. An optional plan takes into account the limits of

existing permits of exploration areas (see figure 7b).

Figure 7: The suggested marine cadastre blocks in the Mediterranean

Sea

With reference to the delimitation of the blocks by coordinates,

there is a basic requirement to define the land block plans along the

coast by official coordinates. In order to achieve this, a pilot project

of CBC was launched in 2006. This project included four areas of 15

block plans each, spread along the coast in four typical environments:

one in a dense urban location, one in a semi-urban location, one in an

agricultural location and one in an open area. The results, which were

published in 2008, were 60 coordinate-based blocks, the coordinates of

50 of which were distributed to surveyors for optional use. The legal

cadastre in Israel still does not adopt coordinates for registration

(Klebanov and Forrai, 2010).

This enables defining coordinate-based marine cadastre blocks

neighboring the land coordinate-based block plans, but these are only

part of the 291 blocks along the coast line. In order to overcome this

problem, the DG of SOI decided to adopt a reference line connecting base

points on the coast by straight lines, to serve as a reference line for

the marine cadastre. The base points were surveyed by GPS and defined by

coordinates to serve as a digital border line between the blocks

adjacent to the coast and the "pure" marine blocks.

In addition, since the maritime boundaries between Israel and Lebanon

in the north and between Israel and Gaza Strip in the south are not yet

mutually agreed upon, the marine cadastre is planned in these areas

until and including the penultimate blocks, leaving the border blocks to

be settled following future political settlement of the delimitation of

the neighboring territorial sea areas. In addition, the DG of SOI

decided to prepare for settlement the marine blocks east of the

reference line landwards, which are opposite the land coordinate-based

blocks, the coordinates of which were determined in the CBC pilot

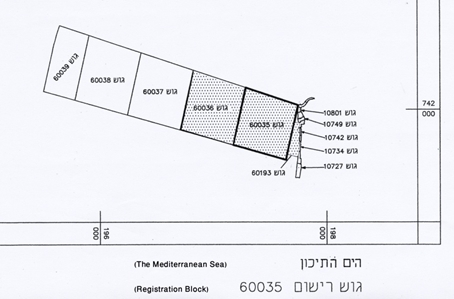

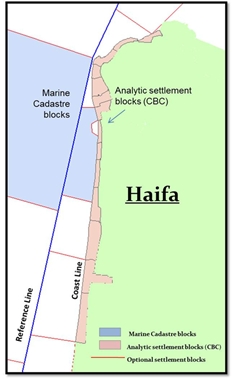

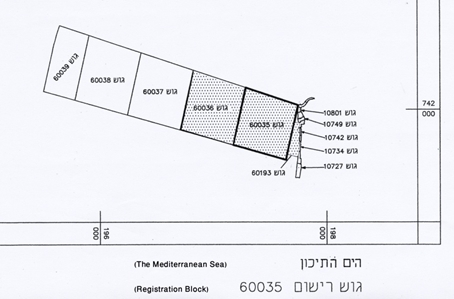

project. An example of such blocks is given in figure 8.

The area between the coastline and the straight reference lines holds

22 settled blocks which had already been settled due to existing land

development along the coast. The marine cadastre blocks, which refer to

this limited area, contain 63 blocks that are in a planning process, and

will be presented graphically in a 1:20,000 scale or larger for

registration.

The estimated number of blocks that are included in the planned

marine cadastre between the above-mentioned straight reference lines and

the outer limit of the Israeli TS is 175 blocks. Most of these blocks,

except the outer limits, cover as previously indicated 5x5 km (see

figure 7a). The blocks can be graphically represented in a scale of

1:20,000.

Figure 8: Example of CBC land block plans along the coast

On the 17th of December 2010 Israel and Cyprus signed an agreement

regarding the maritime delimitation line of the EEZ between the two

States.

The agreement was ratified in February 2011 and deposited with the

UN. This was an important step regarding the delimitation of Israeli

rights in the Mediterranean Sea.

Figure 9: The EEZ delimitation line between Israel and Cyprus (On

Admiralty Chart 183)

This agreement fully coincides with the EEZ delimitation agreements

between Cyprus and Egypt (2003) and between Cyprus and Lebanon (2007).

The agreement left a level of flexibility for defining final common

tri-points between the relevant states at the edges of the delimited

line.

Following this agreement, one can see that the marine area in which

Israel has exclusive economic rights is in the magnitude of the Israeli

land area.

4. THE METHODOLOGY AND THE PRACTICAL IMPLEMENTATION

As mentioned earlier, the DG of SOI and the Director of the Land

Registry, agreed to promote a land settlement in the marine area. They

agreed to begin with a pilot project of a marine cadastre in the TS of

Israel, where Israeli law is fully applicable, and at a second stage,

explore the legal feasibility of initiating settlement proceedings in

the EEZ. In the EEZ Israel has limited rights according to customary

international law, among them the rights to exploit natural resources,

including gas and oil. The project included three marine cadastre

blocks.

The methodology

The recommended methodology of implementing a marine cadastre in

Israel follows the basic methodology used in the Israeli land settlement

process:

- General planning of the area to be settled;

- Public declaration by a land settlement officer regarding land

settlement in specified areas, announcing that potential claimers may

submit claims for ownership and for rights of use in these areas.

- Submitting claims;

- Publishing a table of claims;

- Checking and validating claims and their limits, including field

checks in the presence of the claimers;

- Concluding a table of rights by the land settlement officer and

publishing it;

- Legal appeals to a District Court (optional).

The technical and practical solution used by SOI for the

implementation was a result of the special circumstances associated with

the marine cadastre, where demarcation is not relevant and the

delimitation of boundaries is actually the process of defining

coordinates.

In order to minimize the problems of the external limit of the

relevant marine area seawards to be settled at this stage, this line was

defined as a line 12 nm from the base line along the coast, actually the

outer limit of the territorial sea. In order to have a proper limit

defined by coordinates, the chosen pilot area was one of the places on

land that underwent a process of transformation to coordinates in the

CBC pilot project (Srebro, 2010). These decisions limited the problems

because the marine blocks should be defined between polygons that are

well defined by coordinates. The area that was chosen for a pilot

project is an area south of the city of Haifa. The relevant coastal land

blocks along this area that were transformed to CBC in 2006 are shown in

Figure 8.

The traditional legal cadastral registration is still based on

graphical documentation. One should consider that the landwards limit of

the blocks along the coast line, which is the cadastral reference in

this area, does not coincide with the coast line existing in the

National GIS, as depicted from aerial photographs. However, it does not

coincide with the coast line defined by the DG to support the law for

the protection of the coastal environment (Srebro, 2008), which is

defined at a level of 0.75 m from the zero of leveling. It also does not

coincide with the exact low water line, which changes with time, or with

the straight base line in this area. In addition, the existing

administrative municipal line in the area does not coincide with the

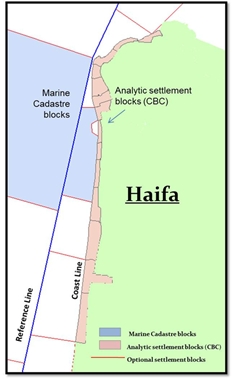

cadastral reference (see figure 10).

The cadastral external line along the coast is a polygon connecting

the external (western) limits of the coastal land blocks. The result of

the decision to use the straight base lines along the coast as

boundaries of marine blocks created the first series of marine blocks

covering the internal waters between the outer limit of the land blocks

and the line connecting the coastal base points (the Reference Line in

figure 10).

The preference for the lateral limits of the first marine blocks was

to refer to existing municipal boundaries, but the municipal limits are

currently undergoing re-definition.

The size of the regular marine blocks between the reference line

connecting the coastal base points and the outer limits of the

territorial sea was defined roughly by 5x5 km cells following the

preference of the land settlement officer (Figure 11).

Figure 10:

A - Various existing reference lines along the coast

B - An enlargement showing the various reference lines

C - Coast line for the Law of Protection of Coastal Environment

The first legal step of the land settlement officer of the District

of Haifa was to declare publicly his intention to settle the specific

area in the near future. This declaration is under article 9 of the Land

Title Settlement Law. This declaration, which is published in Reshumot

(the official gazette of the Government), in newspapers and on the

internet, provides notices to people or organizations that have claims

regarding the area specified in the declaration; they can submit their

claims within the period specified in the public announcement (two

months). This declaration was published on July 12, 2011.

During the specified period, the land settlement officer has to

announce a formal visit to the area, to serve as an opportunity to show

all potential claimers the area of settlement and to give a chance to

any claimer to show the physical limits of his claim.

This procedure, which is a standard procedure in land settlement, was

also used for the settlement of the marine blocks. But since visual

physical features in the sea are rare, unlike the situation on land, an

alternative was found by organizing a sailing expedition to inspect the

marine blocks that were nominated in the published declaration.

Figure 11: The scheme of the final cadastral blocks at the area of

the pilot project

Under another regulation, the formal visit to the area should be

publicly announced (in the printed and electronic media) 14 days in

advance. This was done and the sailing expedition to the area took place

on September 8, 2011.

As an expression of the "historical" moment in implementing a marine

cadastre in Israel, both the DG of SOI and the Director of Land Registry

and part of the relevant staff were on board the ship.

There were no private claimers who joined the expedition, but the

leading claimer attended it. He was a senior representative of the

Israeli National Land Authority, which is responsible for the management

of all State owned lands. This reflected the fact that the Government of

the State of Israel claims ownership over the area under Art.108 of the

1969 Land Law.

The trip took half a day following mainly the limits of the blocks,

but no physical evidences were found except a few buoys. The sea bed was

also explored by sonar and no unusual findings were registered there

either.

Following this formal visit to the area, the land settlement officer

made decisions regarding the limits of ownership and right of use in the

relevant blocks (specific strip parcels were assigned for a

communication cable in the area). SOI prepared final block plans

following the instructions of the land settlement officer. These block

plans were signed officially, as required by law, by the DG of SOI. Then

the land settlement officer published his decisions about the assignment

of ownership and rights of use within these blocks and the blocks were

registered at the beginning of October 2011. Following the successful

pilot project, SOI and the Land Registry continue their cooperation

regarding the settlement of marine blocks. At the end of summer 2014: 16

marine blocks were fully registered and an additional 13 marine blocks

are close to their final approval before registration. An additional 106

marine blocks are included in a bi-annual plan to begin the land

settlement process, not including the marginal blocks along the limits

of the territorial sea zone.

Figure 12: Status of southern marine cadastre blocks (white blocks -

finally registered blocks; green blocks – before final approval)

Following this process but with no direct connection, the DG of the

Ministry of Interior – the Ministry responsible for defining municipal

boundaries in Israel - nominated a committee to define the boundaries in

the sea of the municipal authorities along the coast line. This step

reflects the growing importance of the marine areas along the coast line

in general and especially for the cities and towns spread along the

coast line. It can propel and accelerate the process of land settlement

in the sea along the coast expanding the marine cadastre. Defining the

new municipal boundaries will influence the internal boundaries within

the first line of marine blocks. When the author appeared in front of

the committee, he recommended that municipal limits be defined in full

coordination with the limits of the cadastral block plans.

This will also require a change in the front series of land blocks in

order to adjust the limits of the blocks to the new external municipal

line either by enlarging existing blocks or by adding new blocks.

Figure 13: Plan for 2014-2015

In addition to this activity, a special committee is expected to be

formed to consolidate inter- ministerial activities, initiating a policy

document regarding the marine areas of Israel. The intention of the

author of this article is that this committee will also promote

collection and integration of data and knowledge, to become the basis of

a marine geospatial data base in which the marine cadastre will be one

of the layers, and thus create a Marine Geospatial Data Infrastructure

as part of the Israeli Spatial Data Infrastructure (ISDI). The marine

geospatial data base will be connected to the land geospatial

infrastructure to form a land-marine geospatial data base.

As part of this effort, SOI is in the process of converting the

hydrographic data included in its series of hydrographic charts to GIS.

One of the major challenges in this process is the different data

standards that are used for land and marine geo-information.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The author has adopted the definition of a marine cadastre regarding

the definition of cadastral borders and not the wide scope of marine

information (a multipurpose marine cadastre).

There is a definite requirement for both, but the issue regarding the

development of a marine spatial data infrastructure should and will be

dealt with separately. The rapid land development and exploitation of

lands along the coasts contribute to the trend of development of the

marine areas. The Israeli sovereign rights in the marine area should be

geo-referenced and referred to a cadastral infrastructure, as early as

possible, in order to obtain more benefits at lower cost as long as

there are no conflicting claims.

The strong requirement to utilize the marine areas of Israel and the

need to prepare the infrastructure for management of rights in this area

resulted in an initiative to implement an Israeli Marine Cadastre

regarding the definition of cadastral borders (Srebro et al., 2010) and

to prepare a plan for such an implementation.

Following this initiative and the following implementation plan,

there was a significant advancement. The Survey of Israel and the Land

Registry have already finished in October 2011 the process of settling

16 marine cadastral blocks and an additional 13 blocks await final

approval. The process of implementation was smooth, fast, and at a low

cost.

In parallel a few other activities connected to the marine

environment developed:

Israel signed a maritime delimitation agreement in the EEZ with

Cyprus; new large gas fields were discovered, requiring the construction

of a conduction and distribution network including coastal terminals; an

effort to delimit the municipal boundaries in the sea was launched,

coastal environment protection regulations and measures have been

implemented; and activities involving integrating governmental data into

the marine area as well as building a Marine Spatial Data Infrastructure

have been considered and practical measures have been taken. These

activities show the importance of fast implementation of a marine

cadastre as long as the cost remains low. The marine cadastre will

contribute to improve planning and coordination and can optimize

investments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author thanks Advocate Alisa Caine the Director of the Israeli

Land Registry at the Ministry of Justice and Mr. Haim Laredo the Land

Settlement Officer of the District of Haifa. The author thanks the

people of the Survey of Israel (SOI) for their help with the data and

most of the figures: Mr. Ronen Regev, the Director General; Mr. Itzhak

Fabrikant, Deputy Director for Cadastre; Mrs. Orit Marom head of the

cadastral department; Dr. Yaron Felus, Chief Scientist; and Mrs. Eti

Benin, Mr. Baruch Peretzman, Mr. Elias Koifman, Mr. Hagi Ronen, Mrs.

Limor Gur-Arie, Mrs. Lea Ezra and Mrs. Rachel Saranga. The author thanks

Mr. Ronie Sade for his support with the figures based on the data of the

National Bathymetry Project and Spot data.

Note: The basic version of this article was written in 2012 when the

author still served as the DG of SOI.

REFERENCES

Agreement on the Delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone between

Israel and Cyprus (2010), signed in Nicosia on 17 December 2010.

Binns A., Rajabifard A., Collier P.A. and Williamson I., (2003),

Issues in Defining the Concept of a Marine Cadastre for Australia,

UNB-FIG Meeting on Marine Cadastre Issues, New Brunswick, Canada, 15-16

September 2003.

Binns A., (2005), Defining a Marine Cadastre – Legal & Institutional

Aspects, Marine Administration Workshop Understanding the Spatial

Dimension, Sydney, Australia, 1 December 2005.

Fulmer J., (2007), The Multipurpose Cadastre Web Map. Presented at

2007 ESRI Survey & Engineering GIS Summit, San Diego, California, June

16-19, 2007.

Byrne T., J.E. Hughes-Clarke, S.E. Nichols and M.I. Buzeta, (2002),

The Delineation of the Seaward Limits of a Coastal Marine Protected Area

Using Non-Terrestrial Subsurface Boundaries – The Musquash Estuary MPA.

Published in the Proceedings of the Hydrographic Conference, Toronto,

Canada, May 2002.

International Hydrographic Organization, (2011), Spatial Data

Infrastructures "The Marine Dimension", Guidance for Hydrographic

Offices, C-17 Edition 1.1.0., February 2011,IHB, Monaco.

Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty (1994), Peace Treaty between the State of

Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 26 October 1994, UNTS 35325

Volume 2402.

Israel-Jordan Maritime Boundary (1996), The Maritime Boundary between

the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 18 January

1996, UNTS 35333 Volume 2403.

Klebanov M. and Forrai J., (2010), Implementation of Coordinate Based

Cadastre in Israel: Experience and Perspectives. Proceedings of XXIV FIG

Congress, Sydney, Australia.

Ng'ang'a S., Nichols S. and Monahan D., (2003), The Role of

Bathymetry Data in a Marine Cadastre: Lessons from Proposed Marine

Protected Area. US Hydrographic Conference, Biloxi, Mississippi, 24-27

March 2003.

Ng'ang'a S., Nichols S., Sutherland M. and Cockburn S., (2001),

Toward a Multidimensional Marine Cadastre in support of good Ocean

Governance, New Spatial Information Management Tools and Heir Role in

Natural Resource Management, International Conference on Spatial

Information for Sustainable Development, Nairobi Kenia, 2-5 October

2001.

Nichols S., Monahan D. and Sutherland M., (2000), Good Governance of

Canada's Offshore and Cadastral zone: Towards an Understanding of the

Marine Boundary Issues. Geomatica, 54 (4) 415-424.

Nichols S., Ng'ang'a S., Cockburn S. and Sutherland M., (2003),

Marine Cadastre: The basis for understanding the use and governance of

marine spaces. Presented on behalf of the Association of Canada Land

Surveyors to the Parliamentary Committee on Oceans, Canada, 17 February

2003.

Robertson B., Benwell G. and Hoogsteden C., (1999), The Marine

Resource: Administration Infrastructure Requirements, UN-FIG Conference

on Land Tenure and Cadastral Infrastructure for Sustainable Development,

Melbourne, Australia.

Shoshani U., Benhamo M., Goshen E., Denekamp S. and Bar R., (2004),

Registration of Cadastral Spatial Rights in Israel – A Research and

Development Project, FIG Working Week Athens Greece, May 2004.

Srebro H., (2008), Definition of the Israeli Coastline, FIG Working

Week 2008, Stockholm, Sweden, 14-19 June 2008.

Srebro H., (2009), The Definition of the Israeli International

Boundaries in the Vicinity of Eilat, FIG Working Week 2008, Eilat,

Israel, 3-8 May 2009.

Srebro H., (2010), On The Way to a Coordinate Based Cadastre (CBC) in

Israel, FIG International Congress, Sydney, Australia, 11-16 April 2010.

Srebro H., Fabrikant I. and Marom O., (2010), Towards a Marine

Cadastre in Israel, FIG International Congress, Sydney, Australia, 11-16

April 2010.

Stein D. and Taylor C., (2009), Working Towards a Multipurpose Marine

Cadastre, Workshop on Best Practices for Marine Spatial Planning, The

Nature Conservancy, Arlington VA, 2009

Sutherland M., (2003), Report on the outcomes of The UNB-FIG Meeting

on Marine Cadastre Issues Held at The Wu Centre, University of New

Brunswick Fredricton, New Brunswick, Canada 15-16 September 2003.

Sutherland M., (2009), Developing a Prototype Marine Cadastre. 7th

FIG Regional Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam, 19-22 October 2009.

United Nations, (1983), The Law of the Sea, Official Text of the

United Nations Convention on The Law of the Sea with Annexes and Index.

United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.83.V.5, New York, 1983.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr. Haim SREBRO received his BSc and MSc degrees from the Technion,

Haifa, in Civil Engineering and Geodetic Engineering and his PhD from

Bar-Ilan University. He was a teacher at the Technion and at Tel-Aviv

University. He served during the years 2003-2012 as the Director General

of the Survey of Israel and as Chair of the Inter Ministerial Committee

for GIS. He is a Co-Chairman of the Israeli-Jordanian Joint Team of

Experts since 1994, responsible for the delimitation, demarcation,

documentation and maintenance of the International Boundary within the

Joint Boundary Commission. Since 1974 he is a leading figure in the

boundary negotiations and demarcations between Israel and its neighbors

and signed the 1994 Peace Treaty between Israel and Jordan and the 1996

Maritime Boundary Delimitation. In 2010 he signed the Israel-Cyprus

Agreement on the EEZ Delimitation.

He was a member of ASPRS since 1978 and a member of ACSM and is a

member of the Israeli Society of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, the

Israeli association of Cartography and GIS, and of the Israeli Chambre

of Licensed Surveyors.

Dr. Srebro was the Conference Director of FIG Working Week 2009 at

Eilat.

He chairs the WG on International Boundaries of FIG Commissions 1.

He was the editor-in-chief of The New Atlas of Israel in Hebrew

(2008) and English (2011), and of the Atlases of the Israeli coast lines

in the Mediterranean Sea (2005) and in the Red Sea and in the Kinneret

(2011). He is co-author of the book 60 Years of Surveying and Mapping

Israel (2009), author of the book The Boundaries of Israel Today (2012),

Editor and co-author of FIG Publication No 59 on International Boundary

Making (2013), and author of a few books in Hebrew.

CONTACTS

Dr. Haim SREBRO

12 Teena St., Maccabim-Reut 7179902, Israel

Tel. +972-(0)50-6221400; Fax + 972-8-9263471

Haim.srebro[at]gmail.com

|