Article of the Month - August 2022

|

Assessing Land Administration Systems and their

Legal Frameworks: A Constitutional Focus

Kehinde BABALOLA, Simon HULL, Jennifer WHITTAL,

South Africa

|

|

|

| Kehinde Babalola |

Simon Hull |

Jennifer Whittal |

This article in .pdf-format

(24 pages)

SUMMARY

Constitutions should provide a legal basis for addressing a country’s

land administration system (LAS) and legal reform. Considering this

vital role, a country’s constitution should be evaluated to ensure that

it supports, in principle, LAS and law reforms that include pro-poor

objectives. In recent years, several land administration assessment

frameworks have been developed, yet none give attention to the

associated legal framework of LAS reform from a constitutional

perspective. It is now commonly recognised that a LAS that is

significant for all people in a developing country should include

pro-poor approaches. A context-specific framework to evaluate a LAS and

its legal framework, specifically the relevant constitution, is lacking.

The study addresses this gap in developing a conceptual framework to

support the holistic evaluation of a country’s constitution in the

context of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The framework development involves

secondary data (constitution, land laws, land policy, legislation, and

published journal articles) collated and assessed using a sampling logic

method. Three key areas of a constitution emerged as important to the

delivery of pro-poor LAS: human rights, rule of law, and legal

pluralism.

The impact of a constitution and potential areas of improvement may

be revealed with the application of the conceptual framework. This study

is aimed at LAS and the reform of its legal framework from a

constitutional perspective. Because the practice of African customary

law is principally in rural and peri-urban areas, it is aimed at

achieving the significance of the LAS for peri-urban and rural land

rights holders. The study is significant for policymakers,

professionals, and academics engaged in the reform of the LAS and its

legal framework in a developing country SSA context.

1. INTRODUCTION

Most national constitutions in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries

give minimal attention to the customary legal framework while devoting

much attention to the statutory legal framework for land administration

(Alden Wily, 2012c). Such constitutional deficiencies may justify

several LAS and legal reform interventions. However, in SSA, many such

reforms have failed to provide significance and success (see Section 1.2

for definitions of significance and success) for customary land

rightsholders (Alden Wily, 2012d): “The crux of the disappointing

results of reforms is the treatment of customary rights. It is still

rarely the case that customary rights have been considered worthy of

equitable legal respect as a form of private property” (ibid.: 14).

Hence, giving relevance to the customary legal framework in the

constitution may bring about significance and success in reform

initiatives.

In SSA countries, the social, economic, and political transformation

has resulted in the ‘proliferation’ of new constitutions. This has

necessitated the adjustment of the ‘conceptual boundaries’ of LAS and

associated legal frameworks (Negretto, 2012; Alden Wily, 2018b). The

extent of recognition of customary legal framework has come to the fore

in SSA countries. In these countries, about 90% of land access is

through customary processes resulting in customary land tenure (Bae,

2021). Moreover, two-thirds of cultivated land in SSA countries is held

under customary tenure (Chimhowu, 2019).

Although LAS and legal reform have been on the agendas of the World

Bank and FAO for the past decades, their approach has been criticised

for lacking thorough assessment of the local context, possibly leading

to inadequate reform interventions (Burns et al. 2006; Boone, 2007;

Zevenbergen, et al. 2013). Several frameworks have been developed to

assess the institutional and technical impacts of LASs on land

rights-holders (for example, Chimhamhiwa, 2010; Ali, Tuladhar and

Zevenbergen, 2010; Akingbade et al, 2012;2014; Emerson et al, 2012;

Yilmaz et al, 2015; Adekola, Krigsholm, & Riekkinen, 2021). However,

these frameworks do not fully consider the role and processes of

customary land administration in their assessment, nor do they give

credence to the value of African customary law in such societies.

A conceptual framework to guide cadastral system development has been

designed for this purpose (Hull, 2019; Hull and Whittal, 2020). The

framework was developed to ensure the three goals of success,

sustainability and significance are present in the development of a

cadastral system (ibid.). It is centred on human rights, pro-poor

policies, and good governance. These triple components of the so-called

3S (success, sustainability, and significance) conceptual framework help

to guide cadastral system development in customary land rights contexts.

Although Alden Wily (2018) evaluates the constitutions of African

states concerning compulsory acquisition, no standard evaluation

framework has been developed for the distinct aspect of LAS and its

legal framework. Effective and efficient LAS with an appropriate legal

framework is essential to ensure tenure security (Alden Wily, 2011;

Subedi, 2016; Ghebru & Okumo, 2017; Otubu, 2018). To achieve this in

land reform projects, researchers and practitioners are encouraged to

understand the LAS of a country in context. In general, the law is

subservient to the constitution of the state, which is the highest law

in the land. The land policy directs both the development of land laws

as well as institutions to deliver on policy goals. But these must be

conducted in line with the provisions of the relevant constitution.

1.1 Aim and Outline

The 3S conceptual framework of (Hull, 2019; Hull and Whittal, 2020)

of guiding cadastral system development addresses success,

sustainability, and significance in customary land rights contexts. It

focuses on LAS reform projects from the policy level down to

implementation. Land administration reform is addressed at the land

policy level. The framework assesses project outcomes against the needs

of customary land rights holders (ibid.). This study focuses on LAS

development at the constitutional level with special emphasis on the

role of the legal framework in LAS reform. The aim is to develop a

conceptual framework for evaluating the constitution in this regard,

ensuring the needs of peri-urban and rural land rights holders are met.

The methodology of the study is explained in section 2. Thereafter,

Section 3 develop a conceptual framework for assessing LAS and its legal

framework. The conclusion is presented in section 4. In the next

section, the definition of terms used in this study is presented to

enable readers to understand the terms as applied to this study.

1.2 Definition of terms

Land reform in post-colonial Africa is concerned with addressing the

impact of colonialism to effect greater equity in landholding and

restore dignity to those previously dispossessed of their land. In

Nigeria, land reform involves legal and land administration (procedural,

governance, and communication) reforms. This may entail removing the

provisions of amendment of the Land Use Act (LUA) from the Constitution,

revoking the powers of the Governor to consent to mortgage transactions

in the assignment of land, and removing the uncertainties hindering

Nigerians from enjoying possessory rights to land (Atilola, 2010;

Mabogunje, 2010; Ibiyemi, 2014). At all levels, this involves adopting

the principles of good governance, democratic land governance, as well

as responsible land administration and management among other things to

allow effective land administration service delivery (see Arko-Adjei,

2011; de Vries and Chigbu, 2017; Hull and Whittal, 2021).

Land tenure reform may involve changing the terms and conditions of

landholding with the primary aim of recognising locally held land rights

and at the same time empowering land rights holders with these rights

(Alden Wily, 2000).

Success, Sustainability, and Significance: These have been defined by

Hull (2019) in terms of cadastral systems development, which includes

LAS reform. The gap between planning and implementation requires

successful intervention (Hull & Whittal, 2020). Suitable goals are

essential to guide the processes. Whether success is obtained is

measured in land administration service delivery. Assessment should be

an ongoing process and built into interventions (Hull & Whittal, 2020)

since LASs should continue to change and adapt to changing contexts.

Successful LAS in the long term can be said to be sustainable - this is

a vital outcome of a reform process (Williamson et al. 2010). When goals

of LAS are not aimed at delivering effective land administration

services, interventions may fail through a lack of significance (Hull &

Whittal, 2020). Land rights holders may not access services due to

inefficiency and ineffectiveness (examples are given by Ghebru & Okumo,

2017 and Nwuba & Nuhu 2018). For a LAS to be successful and sustainable,

significance must be built-in (Hull and Whittal, 2020).

Rule of Law: Rule of law is a:

“… principle of governance in which all persons, institutions, and

entities, public and private, including the State itself, are

accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced, and

independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international

human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to

ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before

the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the

law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal

certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal

transparency” (United Nations 2004: 4).

In sum, the rule of law implies that no person, natural or juridical, is

above the law.

Legal pluralism is defined by many as the co-existence of two or more

laws or legal systems within a geographical space (Merry, 1988;

Griffiths, 1986; Pimentel, 2011; Ndulo, 2017; Fisher & Whittal, 2020).

In this paper legal pluralism is defined as a condition or system in

which two or more states, groups, principles, sources of authority,

etc., coexist in a manner that there are devolution, decentralisation,

self-determination, and autonomy for individual bodies in preference to

monolithic state control. In former African colonies, legal pluralism is

most often used to describe the coexistence of African customary law and

received colonial law (noting that these hybrids are ever-evolving)

along with their different LASs. While the received law is mainstreamed,

African customary law may often not be recognised, but even if it is, it

may be treated as inferior and archaic.

Human rights refer to the claims entitled by every human being under

his or her humanity (OHCHR, 2021), irrespective of race, sex, gender,

nationality, ethnicity, colour, language, and religion or social group.

The rights to life and liberty, the freedom of opinion and expression,

the right to work and education, and many more are rights to which

people are entitled without any form of discrimination (United Nations,

ND). It is, however, noted that there is no basic human right to land.

1.3 Contribution to literature

Many countries have initiated reform in land tenure and LAS (Norfolk

& Tanner, 2007; Deininger et al. 2008; Benjaminsen et al. 2009;

Kapitango & Meijs, 2010; Sagashya & English, 2010) with varying degrees

of success and failure. The failure of LAS reform in Africa is

attributed to a lack of attention to the legal status and economic

activities of the poor (Mowoe, 2019). Land tenure reform initiated in

Nkoranza South Municipality, Ghana failed because state policies did not

sustain communal practices, land use dynamics and cultures (Anaafo,

2015). Land access and use in Ghana requires “communal dynamics” in

regulating land rights (Anaafo, 2015: vii). In South Africa, land tenure

form is not successful because of “inappropriate logic “of land reform

(Cousins, 2016) which is not significant for land right holders (Hull &

Whittal, 2017). Land tenure reform in Mozambique is considered exemplary

because all land rights holder were accommodated under a single Act and

backed with full legal protection (Tanner, 2002).

Land administration reform was carried out in Ghana, Uganda,

Tanzania, and Ethiopia with decentralization as the central aim of

reform. Ghana and Uganda recognised customary land tenure through the

legal framework with traditional institutions playing important roles

(Byamugisha, 2014). They harmonised customary and statutory rights and

institutions. Ethiopia and Tanzania replaced traditional authorities

with civil community-level institutions with less recognition of

customary land rights (ibid). In Ethiopia and Tanzania formalization of

landholders as holders of statutory and not customary rights was carried

out. For the countries under study, there was an extension of the

central government LAS. Financial and social sustainability is key to

the legal challenges attributed to land administration reform (ibid,

Hull and Whittal, 2020). The developed framework will help address

social sustainability.

The development of this conceptual framework will help address one of

the main legal challenges associated with LAS reform. The legal

challenges relate to the adoption of replacement theories instead of

adaptation theories (see Hull, Babalola and Whittal, 2019) in legal

framework for land administration. In addition is the interaction of

inherent and inherited legal framework which affects LAS reform in SSA.

Inherent means legal framework in existence pre-colonial while inherited

means legal framework brought about by colonisation (see Hull and

Whittal, 2021). The latter is used to supress the former making LAS

reform in SSA not to be context-specific. Efforts are geared towards

making customary legal framework for land administration evolve.

Equity regarding respect and recognition of customary land

administration alongside statutory land administration has been at the

forefront in recent debates in Africa and elsewhere (Mamdani, 1996;

Cuskelly, 2011; Diala, 2019; Diala & Kangwa, 2019; Osman, 2019).

Researchers, including anthropologists and social scientists, have

contributed from a range of disciplines. Some of these studies explain

the mode of indirect rule of the colonial land administrators in former

colonies. On the one hand, indirect rule was adopted to co-opt customary

institutions within colonial land administration processes because the

colonial administrators recognised the strength of “indigenous rulers”

(Ismail, 1999: 7). On the other hand, indirect rule enabled colonial

administrators to control land in rural areas (Ntsebeza, 2005).

Subsequently, the trend of replacing indigenous African customary land

law with colonial land law was motivated by western values and the

commodification of land as a capital resource. At independence, the

formerly colonised new states adopted the constitutions and land

policies of their former colonial administrations (Alden Wily, 2012b).

Leaders in the new states viewed customary land rights and tenure as a

relic of a past era that would eventually evolve into western land

rights and tenure. In the meantime, customary institutions have remained

in place in underdeveloped rural areas of the country, administered by

traditional authorities largely outside of, and unrecognised by,

constitutions, laws, and state organisations. Improving the legal status

of customary land rights in Africa is hence a major concern in the

region (Alden Wily, 2018a). To improve the legal status of customary

land rights and recognition of African customary law, the paper develops

a conceptual framework addressing improvements in LAS and the reform of

legal framework (including constitutional law) for peri-urban and rural

areas.

2. METHODOLOGY

This paper used a desktop review of secondary data using a

‘text-based approach’ to draw on a range of secondary data sources

including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, doctoral

thesis, books, briefs on policy issues to identify gaps in land reform.

These sources reflect on land reform land tenure reform, human rights,

rule of law, and legal pluralism that are specific to the SSA context.

The subject search included secondary data sources dealing with LAS

reform, land tenure reform, legal frameworks, cadastral systems, human

rights, LAS, legal pluralism, and rule of law and land laws as about LAS

reform. Documents published since 2010 were included in the sources

used.

The search criteria used to identify sources are as follows:

- The combinations of the following phrases: land, LAS reform,

land tenure reform, rule of law, human rights, and legal pluralism

was used to interrogate for peer-reviewed journal articles,

conference papers, doctoral thesis, books, briefs on policy issues.

using (Google Scholar, Springer Link, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR).

- Literature is limited to English publications.

- Publications include peer-reviewed journal articles,

conference papers, doctoral thesis, books, briefs on policy issues

- Sources are focused on SSA and other developing contexts.

By reading through the title and abstract a ‘saturation sampling

logic’ was used and a final list of 16 publications (see Table 2-

Appendix for the full list) was selected. Additional texts dealing with

human rights and constitutions, but not specifically related to land,

categorises emerged during the sampling process. (See Table 3-Appendix).

The sources were considered sufficient enough to address the research

objective in that additional sources are not likely to affect the

research findings.

Coding and categorisation of the source documents were undertaken

using NVivo which helps with data transparency and reliability of the

findings. NVivo is a multi-tasking software allowing researchers to make

meaning from bulky qualitative data. The process helps further

researchers to be able to replicate the research. Coding and

categorisation of the information were conducted. Coding means the

identification of key topics and explanation of these topics with ‘brief

catch phrases’ (Allan, 2003). In an attempt to identify themes from the

literature, similar codes are grouped into concepts with similar

concepts grouped into categories.

The source text was imported into NVivo 12, and the text is

categorised as human rights, rule of law, and legal pluralism. The key

aspect of the research is the constitution of the country in question;

the elements investigated in line with this aspect are human rights,

rule of law and legal pluralism (defined in section 1.2). Through

coding, these elements are identified in the literature using different

colours. During the coding, potential indicators emerged which, together

with the elements, provide for the conceptual framework for assessing

the LAS from a constitutional (aspect) perspective. These indicators are

described in section 3.

3. EVALUATION FRAMEWORK FOR CONSTITUTION IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICAN

COUNTRIES

Each constitution is the supreme law of the land – it should provide

the basis of operation for land policy and land law of any country. This

means all laws must be developed in line with constitutional principles

(International IDEA, 2011; Fisher & Whittal, 2020). A constitution

should describe the social, economic, and political use of land, forming

the intersection between the legal, political, and social systems

(Bulmer, 2017). A constitution should set out in clear terms how it

proposes to address rule of law, human rights and, when relevant legal

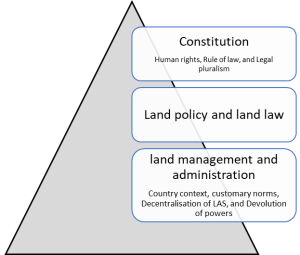

pluralism, concerning LAS (Pimentel, 2011; Diala, 2018). Figure 1

illustrates the role of the constitution concerning land policy and land

management in LAS. The triangle shows the constitution at the apex with

the land policy and land law at a level below the constitution drawing

on principles from the constitution for its enactment. The land

administration and land management stands at a level below the land

policy operating on the principles of the land policy. The

constitutional reform links the constitution to human rights, rule of

law, and legal pluralism in LAS.

Three aspects of constitutions are discussed: human rights, rule of

law, and legal pluralism (see Figure 1; Table 1). While human rights and

the rule of law are observed in many constitutions in SSA, there is a

general deficiency in recognition of the reality of legal pluralism

within constitutions (Pimentel, 2011). According to Alden Wily (2018b),

reform in LAS should be embedded in the constitution of every country.

State-citizen property relations need to have their basis in the

constitution (ibid.). Beginning with constitutional reform addressing

the three pillars of human rights, rule of law, and legal pluralism, LAS

reform that follows will be more likely to be successful, sustainable,

and significant

Figure 1. LAS and its legal framework: linking human

rights, rule of law, and legal pluralism to Constitution

Land policy and land law should flow from the constitution. The

administration of land flows naturally therefrom. The constitution is a

symbol of a social compact between the governors and the governed

(Bulmer, 2017). As stated by Hull and Whittal (2017), customary needs,

norms and values are necessary as part of the process of policy and

legislation formulation which is equally applicable to the process of

the constitution formulation. This should involve the active

participation of the populace, else a disconnect occurs between the

government and the governed, leading to a loss of significance for the

people. This may negatively influence the success and sustainability of

policies and laws emanating from the constitution.

Potential indicators are identified using the conceptual framework of

the constitution being the additional aspect added to the framework of

Hull (2019) with its associated elements: human rights, rule of law and

legal pluralism. The results of this investigation are reflected below.

3.1 Human Rights

Van der Molen highlights that although a human right to land or land

access is contested and not globally recognised, “… a human right to

property is not about the relationship between a human being and land …,

but about the relationship between a human being and the state. It

concerns the protection of the individual against interference by the

state” (Prah, 2013; Van der Molen, 2016, 54). Measures of protection

should not be against unlawful and non-legitimised state interference

alone but also against coercive pressures by elite groups and the

powerful (Van der Molen, 2016).

Human rights are either substantive or procedural (Van der Molen,

2016). Two aspects of human rights concerning LAS should be incorporated

in constitutions. Substantively, the constitution should reflect respect

for land rights, whether registered, unregistered, individual, communal,

or extra-legal (ibid.). The constitution should define land tenure and

land rights through legislation and customary law (Prah, 2013; see Hull

and Whittal, 2021). How land tenure and land rights are

constitutionalised is of primary importance for peri-urban and rural

dwellers (Randolph & Hertel, 2012).

Many human rights require positive and negative obligations to be

performed by the state (Akandji-Kombe, 2007). Considering positive

obligations, the state might adopt a legal framework that reflects legal

pluralism in the sense that land rights holders can have access to land

without any form of discrimination in terms of culture, laws, and

administration. Negative obligations entail that the state desists from

unlawful land acquisition, forced evictions and excessive land use

controls (Mchangama, 2011). Any form of deprivation in property rights

should require sufficient compensation provided for in the constitution

(Alden Wily, 2018b). The absence of such sufficient compensation by the

state can be termed a violation of human rights (Van der Molen, 2016;

Alden Wily, 2018b). Hence, according to the human rights tradition,

citizens expect that the state will not deprive them of their land

rights for arbitrary reasons outside of laws of general application.

Such arbitrary reasons could be based on social constructs such as

status, gender, or race (Van der Molen, 2016). The state likewise has an

obligation towards the citizens to respect, protect and promote their

land rights. The positive obligation requires the state to regulate

something rather than do something– in other words, the state is not

expected to provide access to land as a human right, although it may

well do so. Rather, the state is expected to protect landholding(ibid.).

3.2 Rule of Law and Legal Pluralism

The rule of law and legal pluralism are interlinked through their

“theoretical formulations” and “practical applications” (Gebeye, 2019:

341). Rule of law and legal pluralism is premised on law and legality

which links both to the instrumentality of law and its institutional

frameworks (Gebeye, 2019). Rule of law is a universal feature of

constitutional regimes describing a cultural commitment (Reynolds,

1986). For LAS to be successful, the constitution should preserve and

promote rule of law (ibid.). In statutory legal reform that begins with

constitutional reform, Schmid (2001) and Berman (2007) identified legal

pluralism as one of the areas embodying both conflict and opportunities.

The rule of law can be described using thinner and thicker

conceptions (Tamanaha, 2004). Thinner conception “means that government

officials and citizens are bound by and abide by the law” (Tamanaha,

2012: 233). This minimalist approach to the definition of rule of law is

adopted in this section because it excludes democracy and human rights.

Democracy is a system of governance. The human rights aspect of the

conceptual framework is already discussed in section 3.1. Using this

minimalist approach rule of law in this study context implies that

governance is based on law and these laws must be publicly available.

These laws must be consistent and not contradictory (Tamanaha, 2012).

The thicker conception deals with the procedure of law-making and

operation as well as the substantive content of the law as it pertains

to good governance, constitutionalism, and social justice (Gebeye,

2019). Gebeye (2019) argues that legal pluralism should be taken

seriously to overcome deficiencies in the conception of the rule of law.

With a thinner conception of rule of law, a lack of written and clear

law may compromise the legitimacy of institutions and even states

(Okoth-Ogendo, 1993; Clapham, 1996). In adhering to a thicker conception

of rule of law, institutions are more likely to protect the interests of

all land rights holders (see also Gebeye, 2019).

Social justice can be used as a measure of the quality of governance

(Diamond, 2008). Therefore, a constitution that aims for the thick

conception should promote social justice. Bennett (2011) supports

providing social justice to the rural and peri-urban populace. The

rights to culture, as-built into a constitution, should include the

acknowledgement and application of customary law as well as the

customary justice system.

Within the body of literature, legal pluralism is either supported or

not. Dissenters do not see a role for legal pluralism in a post-colonial

constitutional state because of the hierarchy between actors and

non-state actors in land administration. In addition, they contend that

statute law has more relevance than customary law in land

administration. Studies on land disputes led researchers to first

describe legal pluralism (von Benda-Beckmann and Turner, 2018). Those in

support advocate strong, weak, and legal dualism (Woodman, 2011;

Rautenbach and Bekker, 2014). Strong legal pluralism is when customary,

indigenous, and religious law operate without state recognition

(Woodman, 1998) while in weak legal pluralism they have state

recognition and may be supported by the law (de jure) as well as

occurring extra-legally (de facto) (see van Asperen, 2011). Where

customary law is enshrined in a constitution, this will be further

supported in other laws and state institutions (ibid.). legal dualism is

the application of international and regional laws (these are formed

through customs, treaties etc. by states) within the constitution of a

state. An example could be building fundamental human rights into a

constitution, as is the case in the Constitution of South Africa.

Alden Wily (2012b) states that the recognition of collective tenure

in the constitution is important as failure to do the same is a major

legal exclusion in the last century. “Land is for social use and must go

to the tiller” (Constitution of Guyana, 1980); in South Africa, it was

declared that “the land shall be shared among those who work it”

(Freedom Charter, 1955), although land policy since 1994 is more complex

than a “land to the tillers” policy. Democratization, agrarian reform,

and restitution are essential elements to be indicated in the

constitution of a state (Alden Wily, 2000; 2008; 2011). In

constitutions, the aspects of human and social rights (such as

recognition of customary law) are essential for building legal pluralism

into the legal framework (Alden Wily, 2018a). The importance of the

constitutional link between customary law and the rights to culture in

the constitution cannot be overemphasised (Diala & Kangwa, 2019).

Merlet & Merlet (2010) stipulate that a legal framework that

acknowledges customary law is likely to include socio-institutional

approaches to land access and land value while a legal framework that

only acknowledges statutory law usually exclusively embraces a

market-based approach to land access and land value. With a

socio-institutional approach, social rules that are legitimate in the

eyes of the users can also be reflected in law and the rules of state

engagement (ibid.; Pimentel, 2011). However, there is a disincentive to

codifying social rules by building them into law – customary land laws

exist because of social processes and social constructions, which are

context-specific, and continuously evolve according to claims and

struggles between social actors (Le Roy, 1996; Lavigne-Delville &

Chauveau, 1998; Merlet, 2007). Once social rules are codified as law,

they are considerably less flexible and less nuanced.

As part of the approach to protecting social tenures, Alden Wily

(2012a) states the reasons to pursue a pro-poor approach to customary

rights: (1) the poor are the majority in the customary sector (75% by

international measures); (2) the poor are most dependent on common

resources, which are the natural capital most easy for states and

private sectors to appropriate; (3) not just the state, but also the

local elites have proven to be best able to manipulate customary norms

in their favour, and at the expense of the poor majority; (4) elites

have proven most able to escape the subordination of rights to customary

landholdings by states.

A form of devolution of administration from the state to non-state

actors is essential (von Benda-Beckmann et al. 2009; Pimentel, 2011;

Krueger, 2016). These administrations can be informed of recording land

rights, protecting land rights, or resolving disputes arising from the

same (Weeks, 2013). In defending land tenure and rights in a situation

of uncertainty, individuals, families, and communities holding

unregistered rights need to be allowed access to easy and cheap

mechanisms to defend their rights (Janse, 2013; Weeks, 2013).

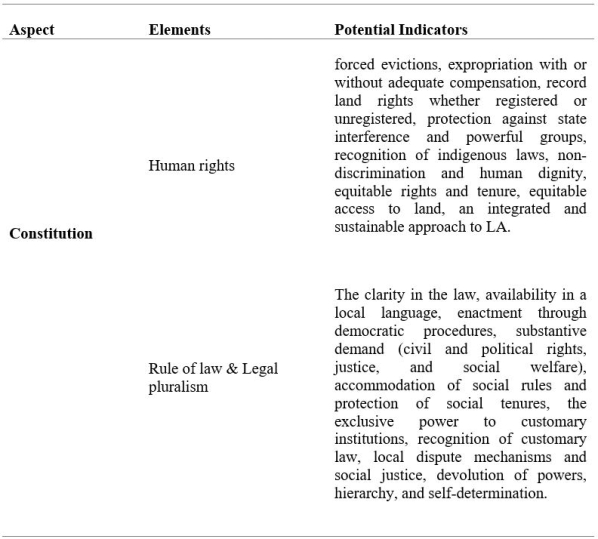

Table 1 shows the conceptual framework resulting from this

investigation. It identifies the potential indicators related to

understanding the LAS and its legal framework concerning the conceptual

framework of the constitutional aspect and its three elements identified

at the outset of the investigation.

Table 1. Elements of the constitution that address

human rights, rule of law and legal pluralism

The contribution in this paper is the extension of the 3S conceptual

framework of success, sustainability, and significance (Hull, 2019) in

the addition of the aspect of constitutional law along with the three

elements and identified indicators. The study also identified an

essential part of the land policy that was missing from the

understanding of the LAS context in the 3S conceptual framework of

success, sustainability, and significance (Hull, 2019).

4. CONCLUSION

LAS and legal reform have failed to provide significance for

customary land rightsholders. It is suggested that this arises out of

reliance of statutory legal framework. As a means of addressing this

gap, a conceptual framework for assessing LAS and legal framework is

proposed. Drawing on the strength of empirical research that uses case

study methodology, a ‘sampling logic methodology’ was adopted to develop

the conceptual framework for evaluating the constitution in the context

of LAS reform. This was achieved by linking the aspects of the legal

framework for LAS reform in the constitution (Figure 1). The framework

is based on human rights, rule of law, and legal pluralism. The

substantive and procedural potential indicators of human rights are

described. It is shown that there is positive and negative obligation to

be performed by the state. As per rule of law and legal pluralism,

socio-institutional approach to land administration may help recognise

customary legal framework for LAS.

The evaluation area – Constitution is proposed to be relevant to LAS

and legal framework development in any context as well as the associated

elements and potential indicators. This is because the focus of this

conceptual framework is geared towards LAS and legal framework reform.

Land administrators and LAS developers operating in any context may find

the conceptual framework effective for the development that ensures the

3S of success, sustainability and significance. It is conceptualised

that reform that will be successful must also be significant and

sustainable for all land rights holders (Hull & Whittal, 2017).

To determine the applicability of the conceptual framework, countries

undergoing LAS and legal reform needs to be interrogated as per their

understanding of LAS and their experiences of LAS and legal reform

concerning the goals of LAS and legal reform and the role of

stakeholders in achieving these goals. The perspective of land

policy-makers and land administrators on LAS and legal reform needs to

be determined. In doing this, the framework will be refined from the

findings of these case studies to keep with the whorled nature of

scientific research (Hull, 2014).

This study focuses on LAS development at the constitutional level

with special emphasis on the role of the legal framework in LAS reform.

The aim is to develop a conceptual framework for evaluating the

constitution in this regard, ensuring the needs of peri-urban and rural

land rights holders are met. This considers the customary law and

integrates this within the constitution. Acknowledgement of the

importance of the constitution reflecting customary law will support

sustainable LAS and legal reform which may address the needs of rural

and peri-urban dwellers in developing contexts. A framework to assess

LAS and its legal framework is developed to target the reform at a

constitutional level.

5. REFERENCES

- Adekola, O., Krigsholm, P., & Riekkinen, K. (2021). Towards a

holistic land law evaluation in sub-Saharan Africa: A novel

framework with an application to Rwanda’s organic land law 2005.

Land Use Policy, 103, 105291.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105291

- Akandji-Kombe, J. (2007). Positive obligations under the

European Convention on Human Rights: A guide to the implementation

of the European Convention on Human Rights. Belgium.

- Akingbade, A., Navarra, D., Zevenbergen, J., and Georgiadou, Y.

(2012). The impact of electronic land administration on urban

housing development: the case study of the Federal Capital Territory

of Nigeria. Habitat International, 36 (2), 324–332.

- Agunbiade, M.E., Rajabifard, A., and Bennett, R., (2014). Land

administration for housing production: an approach for assessment.

Land use policy, 38, 366–377.

- Alden Wily, L. (2000) Natural Resource perspectives DFID

Department for International Development Land Tenure Reform and The

Balance of Power in Eastern and Southern Africa, Number 58, June

2000. Available at

https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=GB2013201868

(14th April 2020).

- Allan, G., (2003). A critique of using grounded theory as a

research method. Journal of business research, 2 (1), 1–10.

- Alden Wily, L. (2008). Custom and commonage in Africa rethinking

the orthodoxies. Land Use Policy. 25(1):43–52. DOI:

10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.02.002.

- Alden Wily, L. (2011). “The Law is to Blame”: The Vulnerable

Status of Common Property Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa. Development

and Change. 42(3):733–757. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01712. x.

- Alden Wily, L. (2012a). Customary Land Tenure in the Modern

World. Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of

Customary Tenure in Africa- Brief 1 of 5.

- Alden Wily, L. (2012b). Putting 20th-Century Land Policies in

Perspective. Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of

Customary Tenure in Africa-Brief 2 of 5

- Alden Wily, L. (2012c). The Status of Customary Land Rights in

Africa Today. Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of

Customary Tenure in Africa-Brief 4 of 5

- Alden Wily, L. (2012d). Land Reform in Africa: A Reappraisal

Rights to Resources in Crisis: Reviewing the Fate of Customary

Tenure in Africa - Brief #3 of 5

- Alden Wily, L. (2014). LDR The Law and Land Grabbing: Friend or

Foe? The Law and Development Review. 7(2):207–242.

- Alden Wily, L. (2018a). The community land act in Kenya

opportunities and challenges for communities. Land. 7(1). DOI:

10.3390/land7010012.

- Alden Wily, L. (2018b). Compulsory Acquisition as a

Constitutional Matter: The Case in Africa. Journal of African Law.

62(1):77–103. DOI: 10.1017/S0021855318000050.

- Ali, Z., Tuladhar, A. & Zevenbergen, J. (2010). Developing a

Framework for Improving the Quality of a Deteriorated Land

Administration System Based on an Exploratory Case Study in

Pakistan. Nordic Journal of Surveying and Real Estate Research.

7(1):30–57.

- Anaafo, D. (2015). Land Reforms and Poverty: The Impacts Of Land

Reforms On Poor Land Users In The Nkoranza South Municipality, Ghana

Institute for Regional Development. The Doctoral Dissertation

University of Tasmania.

- Arko-Adjei, A. (2011). Adapting land administration to the

institutional framework of customary tenure: The case of peri-urban

Ghana [Delft University of Technology].

https://doi.org/978-1-60750-746-8

- Bae, Y. J. (2021). Analysing the changes of the meaning of

customary land in the context of land grabbing in Malawi. Land,

10(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/land10080836

- Bennett, T.W. (2011). Legal Pluralism and the Family in South

Africa: Lessons from Customary Law Reform. Emory International Law

Review. 25:1303–1407. DOI: 10.3868/s050-004-015-0003-8.

- Benjaminsen, T.A., Holden, S., Lund, C. & Sjaastad, E. (2009). A

formalisation of land rights: Some empirical evidence from Mali,

Niger and South Africa. Land Use Policy. 26(1):28–35.

- Berman, P. S. (2007). Global legal pluralism. Southern

California Law Review, 80(6), 1155–1237.

https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139028615

- Boone, C. (2007). Property and constitutional order: Land tenure

reform and the future of the African state. African Affairs,

106(425), 557–586.

https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adm059

- Bulmer, E. (2017). What is a constitution? Principles and

Concepts. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral

Assistance 1–12. Available

https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/what-is-a-constitution-primer.pdf

- Burns, T., Grant, C., Nettle, K., Brits, A., & Dalrymple, K.

(2006). Land Administration Indicators of success, future

challenges. October 1–209.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1667-4_15.

- Byamugisha, F.F.K. 2014. Agricultural Land Redistribution and

Land Administration in Sub-Saharan Africa Case Studies of Recent

Reforms. F.F.K. Byamugisha, Ed. Washington, D.C. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0188-4.

- Clapham, C. 1996. Africa and the International System: The

Politics of State Survival. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Chimhamhiwa, D. (2010). Towards a framework for measuring end to

end performance of land administration business processes – a case

study. Computers, environment, and urban systems, 33 (4), 293–301

- Chimhowu, A. (2019). The ‘New’ African Customary Land Tenure.

Characteristic, Features and Policy Implications of a New Paradigm.

Land Use Policy, 81, 897–903.

- Cousins, B. (2016). Land reform in South Africa is sinking. Can

it be saved? Available.

https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/Land__law_and_leadership_-_paper_2.pdf

- Cooper, H. (1998). Synthesizing Research: A guide for literature

reviews. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Cuskelly, K. 2011. “Customs and Constitutions: State Recognition

of Customary Law around the World.” International Union for

Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. https://por

tals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2011-101.pd

- de Vries, W. T., & Chigbu, E. . (2017). Responsible Land

Management-Concept and application in a territorial rural context

Verantwortungsvolles Land management im Rahmen der Ländlichen

Entwicklung. 2, 65–73.

- Deininger, K., Ali, D.A., Holden, S. & Zevenbergen, J. (2008).

Rural land certification in Ethiopia: Process, initial impact, and

implications for other African countries. World Development.

36(10):1786–1812

- Diala, A.C. (2018). Legal Pluralism and Social Change: Insights

from Matrimonial Property Rights in Nigeria. In In the shade of an

African Baobab: Tom Bennett’s Legacy. JUTA & Company. 155–174.

- Diala, A. C. (2019). A butterfly that thinks itself a bird: the

identity of customary courts in Nigeria’, The Journal of Legal

Pluralism and Unofficial Law. Routledge, 0(0), pp. 1–25. DOI:

10.1080/07329113.2019.1678281.

- Diala, A. C. and Kangwa, B. (2019) ‘Rethinking the interface

between customary law and constitutionalism in sub-Saharan Africa’,

De Jure Law Journal, 52(1), pp. 189–206. DOI:

10.17159/2225-7160/2019/v52a12.

- Diamond, L. (2008). Progress and Retreat in Africa: The Rule of

Law versus the Big Man. Journal of Democracy. 19(2):138–149.

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., and Balogh, S., (2012). An

integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of

Public administration research and theory, 22 (1), 1–29.

- Fisher, R., & Whittal, J. (2020). Cadastre: Principles and

Practice (Fisher, R and Whittal, J. (ed.); First edition. South

African Geomatics Institute.

- Freedom Charter of ANC, (1955). Available

http://www.historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/inventories/inv_pdfo/AD1137/AD1137-Ea6-1-001-jpeg.pdf

(Accessed: 10th September 2021).

- Gebeye, B.A. (2019). The Janus face of legal pluralism for the

rule of law promotion in sub-Saharan Africa. Canadian Journal of

African Studies. 53(2):337–353. DOI: 10.1080/00083968.2019.1598452.

- Ghebru, H. and Okumo, A. (2017) Land Administration Service

Delivery and its Challenges in Nigeria: A Case Study of Eight

States. Available at:

http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/131035/filename/131246.pdf

(Accessed: 1 December 2018).

- Griffiths, J. (1986). “What is Legal Pluralism?” Journal of

Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 24: 1–55

- Hull, S. (2014). Analysing the cadastral template using a

grounded theory approach. In: W. Jennifer, ed. AfricaGEO. Cape Town:

CONSAS Conference, 1–16.

- Hull, S., & Whittal, J. (2017). Human Rights in Tension: Guiding

Cadastral Systems Development in Customary Land Rights Contexts.

Survey Review, 1–18 (October).

https://doi.org/10.1080/00396265.2017.1381396

- Hull, S., & Whittal, J. (2018). Filling the Gap: Customary Land

Tenure Reform in Mozambique and South Africa. South African Journal

of Geomatics, 7(2), 102–117.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sajg.v7i2.1

- Hull, S., Babalola, K., & Whittal, J. (2019). Theories of Land

Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa.

Land, 8(172), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110172

- Hull, S.A. & Whittal, J. F. (2020). Achieving Success and

Sustainability Through Significance: A Cross-case Analysis of

Cadastral Systems Development in Europe and Africa. FIG Working Week

2020 Smart Surveyors for Land and Water Management Amsterdam, the

Netherlands, 10–14 May 2020, May 1–23.

- Hull, S. & Whittal, J. (2021). Human Rights and Land in Africa:

Highlighting the Need for Democratic Land Governance. In Human

Rights Matters. 1–20.

- Hull, S., & Whittal, J. (2021). Do Design Science Research and

Design Thinking Processes Improve the ‘ Fit ’ of the Fit-For-Purpose

Approach to Securing Land Tenure for All in South Africa ? Land,

10(484), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050484

- Ibiyemi, A. (2014). Making a Case for Review of the Land Use Act

– A Focus on Claims for Compensation in the Rural Areas. Lagos State

Polytechnic Journal of Technology, 1(2), 216–235.

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

(International IDEA), 2011. A Practical Guide to Constitution

Building: Principles and Cross-cutting Themes. Available

https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/practical-guide-to-constitution-building/a-practical-guide-to-constitution-building-chapter-2.pdf

(3rd December 2021).

- Ismail, N. (1999). Integrating indigenous and contemporary local

governance: issues surrounding traditional leadership and

considerations for post-apartheid South Africa. Unpublished (PhD

dissertation) Doctor of Administration thesis, University of the

Western Cape, Bellville.

Janse, R. (2013). A Turn to Legal Pluralism in Rule of Law

Promotion? Erasmus Law Review, 3(4), 181-.

http://www.erasmuslawreview.nl/tijdschrift/ELR/2013/3_4/ELR-D-13-00010.pdf

- Kapitango, D. & Meijs, M. (2010). Land registration using aerial

photography in Namibia: cost and lessons. In Innovations in Land

Rights Recognition, Administration, and Governance. Deininger, K.,

C. Augustinus, C., Enemark, S. & Munro-Faure, P. Eds. Washington,

DC. 1–251. Available: www.worldbank.org/rural [2019, March 29]

- Krueger, J. S. (2016). Autonomy and morality: Legal pluralism

factors impacting sustainable natural resource management among

miraa farmers in Nyambene Hills, Kenya. Journal of Legal Pluralism

and Unofficial Law, 48(3), 415–440.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2016.1239318

- Lavigne Delville P., Chauveau J. P. (1998) « Quels fondements

pour des politiques foncières en Afrique francophone » in: P.Lavigne

Delville (ed .) Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale?

», Karthala, Paris

- Le Roy, E., (1996) “La théorie des maîtrises foncières“in : E.

Le Roy, A. Karsenty, A. Bertrand (eds.) La sécurisation foncières en

Afrique, pour une gestion viable des resources renouvelables,

Karthala, Paris

- Mabogunje, A. L. (2010) Land Reform in Nigeria: Progress,

Problems & Prospects. Available at:

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1236436879081/5893311-1271205116054/mabogunje.pdf

(Accessed: 2 August 2018).

- Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and

the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

- Mchangama, J. (2011). CATO Policy Report, May/June 2011 the

right to property in global human rights law.

Merlet, M. (2007) Proposal paper. Land Policies and Agrarian

Reforms, Paris, Agter, available

http://agter.org/bdf/_docs/merlet_2007_11_land-policies-proposal-paper_en-pt.pdf

(26th March 2021)

- Merlet, P. & Merlet, M. (2010). Legal pluralism as a new

perspective to study land rights in Nicaragua. A different look at

the Sandinista Agrarian reform. In “Land Reforms and Management of

Natural Resources in Africa and Latin America” Lleida, 24-25-26

November 2010. Lleida. 1–20. Available: www.agter.asso.fr [04

September 2019].

- Merry, S. E. (1988). Legal pluralism. Law & Society Review 22

(5): 869-896. —. 1992. Anthropology, law, and transnational

processes. Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 357-379.

- Miller, D. (1976). Social justice. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mowoe, M. (2019). Land Policies in Africa: A case study of

Nigeria and Zambia. In the Trajectory of Land Reform in the

Post-Colonial African States: The Quest for Sustainable Development

and Utilization. 1st ed. A.O. Akinola & H. Wissink, Eds. Springer

International Publishing AG. 75–90. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-78701-5.

- Negretto, G. (2012). Replacing and amending constitutions: The

logic of constitutional change in Latin America” Law & Society

Review46/4

- Ndulo, M. B. (2017). Legal Pluralism, Customary Law and Women’s

Rights. Southern African Public Law, 32(1), 1–21.

- Norfolk, S. and Tanner, C. (2007). Improving tenure security for

the rural poor. Mozambique country case study. FAO Legal Empowerment

of the Poor Working Paper. Available:

http://www.fao.org/3/a-k0786e.pdf [2019, January 05].

- Ntsebeza, L. (2005). Democracy Compromised: Chiefs and the

Politics of the Land in South Africa. Leiden: Brill.

- Nwuba, C. C., & Nuhu, S. (2018). Challenges to Land Registration

in Kaduna State, Nigeria. African Real Estate, 1(1), 141–172.

https://doi.org/10.15641/jarer.v1i1.566.Abstract

- OHCHR, (2021). What are Human Rights? Available

https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/pages/whatarehumanrights.aspx

(16th November 2021).

- Okoth-Ogendo, H.W.O. (1993). Agrarian Reform in Sub-Saharan

Africa: an assessment of state responses to the African agrarian

crisis and their implications for agricultural development. In Land

in African Agrarian Systems. T.J. Bassett & D.E. Crummey, Eds.

Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. 247–273.

- Osman, F. (2019). The consequences of the statutory regulation

of customary law: An examination of the south African customary law

of succession and marriage. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal,

22(22). https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2019/v22i0a7592

- Otubu, A. (2018). The Land Use Act and Land Administration In

21st Century Nigeria: Need for Reforms. Journal of Sustainable

Development Law & Policy. 9(1):81–108.

- Pimentel, D. (2011). Legal Pluralism in Post-Colonial Africa:

Linking Statutory and Customary Adjudication in Mozambique. Yale

Human Rights Development Law Journal, 14(1), 59–104.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1668063

- Prah, K.K. (2013). Culture, Rights and Political Order in

Africa. In African Culture, Human Rights and Modern Constitutions.

T. Nhlapo, E. Arogundade, & H. Garuba, Eds. Cape Town, South Africa.

1–51. Press.

- Randolph, S. and Hertel, S. 2012. The right to food: a global

overview. In: L. Minkler, ed. The state of economic and social human

rights: a global overview. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, pp. 21–60.

- Rautenbach, C., and. Bekker, J. C. (2014).Introduction to Legal

Pluralism in South Africa. Durban: LexisNexis.

- Reynolds, N.B. (1987). Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law.

79–104. Available: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub [2020,

November 27].

- Sagashya, D. & English, C. (2010). Designing and establishing a

land administration system for Rwanda: a technical and economic

analysis. In Innovations in Land Rights Recognition, Administration,

and Governance. K. Deininger, C. Augustinus, S. Enemark, & P.

Munro-Faure, Eds. Washington DC, USA: World Bank. 43. Available:

https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2009/fig_wb_2009/papers/sys/sys_2_english_sagashya.pdf

[2019, April 03]

- Schmid, U. (2001). Legal pluralism as a source of conflict in

multi-ethnic societies: The case of Ghana. Journal of Legal

Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 33(46), 1–47.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2001.10756551

- Steudler, D., Rajabifard, A., Williamson, I.P. (2004).

Evaluation of Land Administration Systems. Land Use Policy.

21(4):371–380. DOI: 10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2003.05.001.

- Subedi, G. . G. P. (2016). Land Administration and Its Impact on

Economic Development (Issue July) [University of Reading].

https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4139.9281

- Tamanaha, B. Z. (2004). On the Rule of Law: History, Politics,

Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Tamanaha, B. Z. (2012). “The History and Elements of The Rule of

Law.” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies. 232–247.

- Tanner, C. (2002). Law-Making in an African Context: The 1997

Mozambican Land Law. Http://www.Fao.Org/Legal/Pub-E.Htm,

- The Constitution of Guyana, (1980). Available

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.constituteproject.org%2Fconstitution%2FGuyana_2009.pdf

(17th November 2021)

United Nations, (2004) “The rule of law and transitional justice in

conflict and post-conflict societies,” Report of the

Secretary-General. Available

http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN /N04/395/29/

PDF/N0439529.pdf?Open Element (30th March 2021).

- United Nations, ND. Human Rights. Available

https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/human-rights/ [2020,

January 12].

- United Nations, ND. What is the Rule of Law? Available

https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/what-is-the-rule-of-law/ [2020,

January 12].

- Van Asperen, P.C.M. (2011). Evaluation of pro-poor land

administration from an end-user perspective: A case-study from

peri-urban Lusaka (Zambia). FIG Working Week 2011, Bridging the Gap

between Cultures, May 18-22, 2011, (Marrakech, Morocco). Available:

https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3A9c68c139-621d-45e7-9da9-a1800e692e0a

[2018, October 08].

- van der Molen, P. (2016). Property, human rights law, and land

surveyors. Survey Review. 48(346):51–60. DOI:

10.1080/00396265.2015.1097594.

- von Benda-Beckmann, F., K. von Benda-Beckmann, and J. Eckert

(2009) ‘Rules of Law and Laws of Ruling: Law and Governance between

Past and Future’, in F. von Benda-Beckmann et al. (eds) Rules of Law

and Laws of Ruling. On the Governance of Law, pp. 1–30. Farnham:

Ashgate.

- von Benda-Beckmann, K. & Turner, B. (2018). Legal pluralism,

social theory, and the state. Journal of Legal Pluralism and

Unofficial Law, 50(3), 255–274.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2018.1532674

- Williamson, et al. (2010) Land Administration for Sustainable

Development. First Edit. New York: Esri

Weeks, S.M. (2013). Traditional Courts Bill: Access to Justice or

Gender Trap?. In African Culture, Human Rights and Modern

Constitutions. T. Nhlapo, E. Arogundade, & H. Garuba, Eds. Cape

Town, South Africa. 1–51. Press.

- Woodman, G.R. (1998). Ideological Combat and Social Observation.

The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. 30:21–59. DOI:

10.1080/07329113.1998.10756513.

- Woodman, G. (2011). “Legal Pluralism in Africa: The Implications

of State Recognition of Customary Laws Illustrated from the Field of

Land Law.” Acta Juridica 2011: 35–58

- Yilmaz, A., Çağdaş, V., and Demir, H., (2015). An evaluation

framework for land readjustment practices. Land use policy, 44,

153–168.

- Zevenbergen, J., Augustinus, C., Antonio, Danilo and Bennett,

R., Antonio, D., & Bennett, R. (2013). Pro-poor land administration:

Principles for recording the land rights of the underrepresented.

Land Use Policy, 31, 595–604.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.09.005

6. APPENDIX

Table 3: Text about Human Rights and Constitution

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Kehinde Babalola appreciates the financial assistance granted by the

FIG PhD foundation and the International Postgraduate Funding University

of Cape Town.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Kehinde Babalola is a PhD student at the University

of Cape Town. He completed his Master of Science in Geomatics

specializing in land administration and cadastral system research in

2018. In 2019 he started his PhD working on land administration systems

and their legal framework. He is a Nigerian registered professional land

surveyor and in 2022 became a South African registered professional

engineering surveyor. He is a member of the Nigerian Institution of

Surveyors and the Geoinformation Society of South Africa.

Simon Hull is a senior lecturer and 2019 PhD

graduate at the University of Cape Town (UCT). His doctoral research was

in the field of customary land tenure reform. He completed his MSc at

UCT in the field of digital close-range photogrammetry in 2000

whereafter he spent two years working as a marine surveyor. He spent a

further four years completing his articles and is a registered South

African Professional Land Surveyor. In 2006 he changed careers and

became a high school Maths and Science teacher in a rural village in

northern Zululand. He has held his current position at UCT since 2012,

where he lectures in the foundations of land surveying, GISc, and

cadastral surveying. His research interests are in land tenure, land

administration and cadastral systems, and the use of GIS to address

Sustainable Development Goals.

Jennifer Whittal is a Professor in the Geomatics

Division at the University of Cape Town. She obtained a B.Sc.

(Surveying) and an M.Sc. (Engineering) specializing in GNSS from the

University of Cape Town. In 2008, Jenny obtained her PhD from the

University of Calgary applying critical realism, systems theory and

mixed methods to a case of fiscal cadastral systems reform. She is a

Professional Land Surveyor and lectures advanced surveying and land law.

Research interests are land tenure and cadastral systems, sustainable

development and resilience in landholding for the poor, historical

boundaries and property holding, and cadastral issues in the coastal

zone.

CONTACTS

Mr Kehinde Babalola, Dr Simon Hull and Prof. Jennifer Whittal

University of Cape Town

School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics

Division of Geomatics, 5th floor Menzies Building, Upper Campus

Cape Town

South Africa

Web site: www.geomatics.uct.ac.za