ABSTRACT

There are two major drivers that are increasingly encouraging

and compelling countries, especially developing countries, to

adopt a Fit-For-Purpose (FFP) approach to land administration.

The first relates to the Global Agenda as set by the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) and other frameworks, such as the New

Urban Agenda, where it is now accepted that security of tenure

is a prerequisite for successful transformational change. The

second is about taking advantage of the opportunities provided

by new and emerging game-changing technology developments that

change the focus from costly, high-tech solutions to providing

fast, low cost, participatory approaches for achieving secure

tenure for all.

This paper initially provides background to the 2030 Global

Agenda and the realisation that many of these goals will not be

achieved without quickly solving the current insecurity of

tenure crisis through the FFP approach to land administration.

New technology and emerging trends for land administration,

identified within the World Bank’s Guide (2017), will then be

reviewed within the context of implementing FFP land

administration solutions. Finally, the paper will review the

lessons learned from implementing FFP land administration

solutions in three developing countries, Indonesia, Nepal and

Uganda, to identify how their country strategies were evolved,

how the FFP land administration guidelines were interpreted and

adapted, how politicians and decision makers signed onto the

approach, and how the mind-set of key stakeholders, including

surveyors, were changed to embrace FFP land administration.

1. INTRODUCTION

Most developing countries are struggling to find remedies for

their many land problems that are often causing land conflicts,

reducing investments and economic development, continuing

poverty, hunger and malnutrition, and preventing countries

reaching their true potential. Existing investments in land

administration have been built on legacy approaches, have been

fragmented, and have not delivered the required pervasive

changes and improvements at scale. While a wealth of literature

emphasizes the need for security of tenure and elaborates on its

benefits, including the opportunities of significantly

contributing to poverty reduction and sustainable development,

the conventional approaches to land administration do not make

this a reality. The standard solutions have not helped the

most needy - the poor and disadvantaged - that have no security

of tenure. In fact, the beneficiaries have often been the elite

and organizations involved in land grabbing. It is time to

rethink these traditional approaches. New solutions are required

that can deliver security of tenure for all, are affordable and

can be quickly developed and incrementally improved over time.

The FFP approach to land administration has fortunately emerged

to meet these simple, but challenging requirements.

2. 2030 GLOBAL AGENDA

There is a broad agreement that, while the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs) provided a focal point for governments,

they were too narrowly focused. The MDGs are now replaced by the

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with a new, universal set

of 17 goals and 169 targets that UN member states are committed

to use to frame their agenda and policies over the next 15 years

(2016-2030), see Figure 1. The goals are action oriented,

global in nature and universally applicable. Targets are defined

as aspirational global targets, with each government setting its

own national targets guided by the global level of ambition, but

taking into account national circumstances. The goals and

targets integrate economic, social and environmental aspects and

recognise their interlinkages in achieving sustainable

development in all its dimensions.

Figure 1. The Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2015).

The SDGs provide a framework around which governments,

especially in developing countries, can develop policies and

encourage overseas aid programmes designed to alleviate poverty

and improve the lives of the poor. In particular, the SDGs

Target 1.4 (secure tenure rights to land) will not be achieved

with conventional land governance. Similarly, the land component

is referred to in target 3 of Goal 2 on ending hunger, and, more

generally in Goal 5 on gender equity, Goal 11 on sustainable

cities, Goal 15 on life on land, and Goal 16 on peace, justice

and strong institutions. These goals and targets will never be

achieved without having good land governance and

well-functioning countrywide land administration systems in

place. The SDGs represent a rallying point for NGOs to hold

governments to account. In other words, the SDGs are a key

driver for countries throughout the world – and especially

developing countries – to develop adequate and accountable land

policies and regulatory frameworks for meeting the goals.

2.1 The Wider Global Agenda

It should be recognised that, next to the SDGs, the wider

global agenda includes a range of global issues, such as

responsible governance of tenure, human rights and equity,

climate change and natural disasters, rapid urbanisation, and

the New Urban Agenda – see Figure 2.

Figure 2. The wider global agenda includes a range of land

related issues.

Solutions to the overall global land issues relate to

alleviation of poverty, social inclusion and stability,

investments and economic development, and environmental

protection and natural resource management. These land matters

are now embedded in the SDGs and the land professionals are the

custodians of the systems dealing with these land issues and

responsible for delivering appropriate land administration

policies and services.

There is a strong requisite for effective monitoring and

assessment of progress in achieving the SDGs as provided through

the annual progress reports (UN 2017). There is a need for

reliable and robust data for devising appropriate policies and

interventions for the achievement of the SDGs and for holding

governments and the international community accountable. Such a

monitoring framework is crucial for encouraging progress and

enabling achievements at national, regional and global level.

This calls for a “data revolution” for sustainable development

to empower people with information on the progress towards

meeting the SDG targets (UN, 2014, p.7).

2.2 The FFP Response

The FFP approach is flexible, includes the adaptability to

meet the needs of society today and the outcome can be

incrementally improved over time, when required. The FFP

approach takes advantage of advances in technology development

that now allows for aerial / satellite imagery to be provided

quickly and at low / affordable costs. These imageries can be

used for identifying and recording the visible boundaries of the

individual land parcels rather than using conventional field

surveys and complying with high accuracy standards. The

identification and recording of visual boundaries is undertaken

in a participatory process involving the local community. The

participatory process may also include “walking the boundaries”

using handheld GPS to capture boundary corners on a tablet

imagery. This simple identification and recording can be

upgraded over time, e.g. triggered in response to social and

legal needs of economic development, investments and financial

opportunities that may emerge over the longer term. The FFP

approach thereby enables land rights to be secured for all in a

timely and affordable way. Similarly, the FFP approach looks at

recording all rights – legal as well as legitimate – and enables

for updating and upgrading over time in accordance with the

continuum of land rights (UN-HABITAT/GLTN, 2008). The FFP

approach also advocates for the use of a flexible ITC approach

and an integrated institutional framework without bureaucratic

barriers.

3. NEW AND EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN LAND ADMINISTRATION

The World Bank, with sponsorship from the Nordic Trust, has

recently published the “New Technology and Emerging Trends: The

State of Play for Land Administration” Guide (World Bank, 2017).

The Guide provides decision support to designers of Land

Administration programs requiring guidance on what new and

emerging technologies could be effectively adopted and

integrated within their programs. The Guide is positioned within

the context of implementing FFP land administration solutions

where technical solutions supporting the implementation of the

spatial framework need to be complemented by appropriate legal

and institutional frameworks. The Guide has the following target

audience:

- World Bank: Staff providing guidance to

developing countries designing their land administration

programs; staff specifying land administration programs for

developing countries;

- Donors: Donors providing guidance and

aid to developing countries designing their land

administration programs;

- Policy & Strategy Makers: Senior civil

servant decision-makers involved in formulating policies in

the land sector; senior level staff in land administration /

management agencies; and

- Implementers: Public and private sector

land professionals involved in land administration; NGOs /

CSOs.

3.1 Fit-For-Purpose (FFP) Land Administration Context of the

WB Guide

The FFP Land Administration approach (Enemark, et al., 2016)

provides an innovative and pragmatic solution to land

administration. The solution is focused on developing countries,

where current land administration solutions are not delivering,

with often up to 90 per cent of the land and population in

developing countries left outside the prevailing formal version.

The approach is directly aligned with country specific needs,

affordable, flexible to accommodate different types of land

tenure, and also upgradable when economic opportunities or

social requirements arise. It is highly participatory, can be

implemented quickly and aimed at providing security of tenure

for all. Most importantly, the FFP approach can start very

quickly using a low risk entry point that requires minimal

preparatory work. It can be applied to all traditions of land

tenure across the globe.

To significantly accelerate the process of recording land

rights, the FFP Land Administration approach advocates the use

of a range of scales of imagery as the spatial framework,

wherever feasible, on which to identify and record visible

tenure boundaries. This fast, affordable and highly

participatory approach is appropriate for the majority of land

rights boundaries. Using imagery also allows the spatial

framework to be used by many other land administration and

management activities and generate wider benefits.

Security of tenure does not in itself require precise surveys

of the boundaries. The most important aspect of security of

tenure for the majority of unregistered land parcels is

identification of the land object and its relation to

neighbouring objects, in relation to the connected legal or

social right. The absolute precision of the survey is less

important, except perhaps in high value land and properties, and

non-visible or contested boundaries when higher precision, but

more costly conventional ground survey methods and

monumentation, may be necessary.

Rather than mandating a single surveying specification for

capturing land rights across an entire country, the FFP approach

supports flexibility in adopting a variety of techniques to

capture the land rights depending on local circumstances, a

flexibility that will ensure lower costs and higher speeds in

the capture of land rights. However, this does require that

those designing the FFP projects are familiar with and able to

select the most suitable options from the myriad of emerging

technologies and solutions that show significant promise in

accelerating the process even more. This raises questions such

as:

- Which imagery (satellite, aerial or drone) and what

resolution are appropriate?

- Should we continue with paper orthophotomaps to support

mapping and adjudication participation? Or should we adopt

mobile technologies?

- How does urban density influence our choice of survey

technique?

- Do community mapping and rights adjudication tools have

a role to play within formal land administration systems,

and can they support mainstream activities?

- Is automatic extraction of linear and settlement

features suitable for land administration?

- Are modern SMS or other mass media approaches

appropriate to raise public awareness of land registration

programs?

- What are the key technological gaps and emerging

trends?

The purpose of the Guide is to provide designers of

country-specific FFP Land Administration strategies with

guidance on the current status of technology and emerging

trends. This should allow the most appropriate technical

solutions to be adopted in designing and implementing the

Spatial Framework for the FFP Land Administration approach. This

guidance aims to ensure that the capture, management and

dissemination of land rights information will be achieved using

the most cost-effective solutions, meets the precision and

accuracy requirements, matches the technical resources within

the country, is compatible with social cultures and can be

implemented quickly over large areas.

Therefore, the Guide should be used in conjunction with the

GLTN sponsored “Fit For Purpose Land Administration: Guiding

Principles for Country Implementation.” (Enemark, et al., 2016).

The FFP concept includes three core components: the spatial, the

legal, and the institutional frameworks – see Figure 3. Each of

these components includes the relevant flexibility to meet the

actual needs of today, yet can be improved incrementally over

time in response to societal needs and available financial

resources. The three framework components are inter-related and

form a conceptual nexus underpinned by the necessary means of

capacity development. Each of the frameworks must be

sufficiently flexible to accommodate and serve the current needs

of the country within different geographical, judicial, and

administrative contexts.

Hence, although the Guide covers technology solutions, it is

imperative that the decision making process on technology is

made with the full understanding of the impact on the legal and

institutional frameworks. Importantly, prior to building the

spatial framework and issuing any certificates of land rights,

it must be ensured that the regulations and institutions for

maintaining and updating the FFP land administration system are

in place. Without the institutional capacity and also incentives

for the parties to update the system in relation to the transfer

of land rights and land transfers, it will quickly be outdated

and unreliable and lead to waste of investments for building the

system in the first place.

Figure 3: The Fit-For-Purpose Concept and associated

Frameworks (Enemark, et.al. 2016).

3.2 Scope of Technology Solutions and Approaches in the

Guide

The Guide reviews and assesses new technology solutions that

are currently operating successfully in land administration

systems, but also emerging disruptive technologies that could

significantly accelerate the land administration processes. This

will allow the risk of when, and if, to adopt this emerging

technology, to be judged. Although there have been advances in

supporting technologies such as enterprise content and document

management, optical character recognition and biometric

recording of individuals, these are not considered within the

Guide. This emerging technology includes, for example:

- Use of social media to engage with land stakeholders;

- Use of appropriate imagery sources (satellite,

airplane or drone) to map parcel boundaries, with AI or

crowd-sourced solutions to extract features from imagery,

and/or extraction of land parcel boundaries from point

clouds if LiDAR is collected simultaneously;

- Use of effective emerging methods for capturing rights

in the field using smartphones or tablets, and/or auto

geo-referencing of interpreted, participatory map-sketching;

and

- Use of cloud and/or blockchain technology for immutable

recording and management of rights.

These are particularly powerful when combined with less

recent technologies, such as:

- Use of freely-available satellite imagery and

OpenStreetMap (OSM) data for reconnaissance mapping of the

study area to identify possible issues and stakeholders;

- Use of portable digital devices and crowdsourcing

techniques to record inhabitants and attitudes (hopes and

fears) about land rights; and

- Use of modern data model standards (LADM and STDM) for

defining, recording and managing rights, restrictions and

responsibilities, especially ensuring no gender or other

bias.

The Guide clarifies which of the identified techniques are

fully operational, what is still in the early piloting phase and

what is still pure research. It is emphasized that the

technologies and approaches reviewed by the Guide do not

represent an exhaustive nor exclusive list, but provides an

indication of good practice and emerging trends that should be

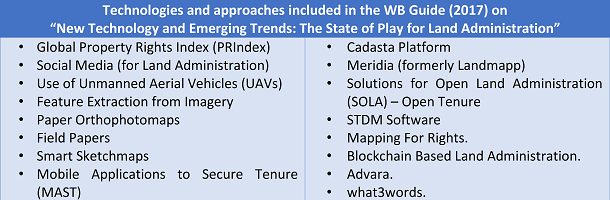

reviewed alongside additional consultations. The technologies

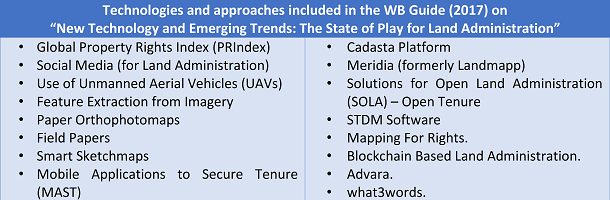

and approaches included in the Guide are shown in the Table 1

below:

Table 1: Technologies Reviewed in Guide

3.3 Structure and Use of the Guide

The Guide leads the reader through the decision-making

process in identifying the most appropriate technology options

to be adopted in their land administration programs. There are

four main parts to the Guide:

- Role of Technology – Information Capture.

- Public Awareness and Preparation.

- Background Information Capture.

- Capturing Land Rights in the Field.

- Role of Technology – Managing, Maintaining and

Disseminating the Information.

- Data Management.

- Data Access.

- Further Key Considerations.

- This section identifies additional considerations

largely beyond the scope of technologies and approaches

reviewed, including institutional and legal frameworks,

capacity development and sustainability.

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Detailed descriptions of the new

and emerging technology solutions.

- Appendix B: Detailed discussion on key

considerations to support choice and implementation of

the technology solutions.

Sections 1 and 2 provide the following decision support

structure:

- A short description on the land administration component

processes covered by the selected section.

- A decision support diagram guiding the user through the

key decisions.

- The main body of text then directly addresses key

considerations and decisions to be made, referring to the

corresponding existing and emerging technology/approach

descriptions in Appendix A and additional ‘key

considerations’ sections in Appendix B.

- Short case study examples provide experiences with

applying the technologies.

The World Bank expects that the Guide will be instrumental in

paving the way forward towards implementing sustainable and

affordable land administration systems in developing countries,

enabling security of tenure for all and effective management of

land use and natural resources. This, in turn, will facilitate

economic growth, social equity, and environmental

sustainability.

4. EXPERIENCES IN IMPLEMENTING FFP LAND ADMINISTRATION AT

THE COUNTRY LEVEL

A well know example of implementing the FFP approach at

country level is the project in Rwanda of demarcating and

recording 10 million land parcels over five years for a cost of

6 USD parcel. This project was completed even before the FFP

principles were launched by FIG and the World Bank (FIG/WB

2014). Currently the FFP approach is being implemented in

countries such as Ethiopia and Mozambique. It should also be

mentioned, that many eastern European countries used such

flexible and low cost approaches in the 1990s when undergoing a

transition from centrally planned to market based economies.

However, the most recent experiences from Indonesia, Nepal and

Uganda are presented below.

4.1 Indonesia

Indonesia is the world´s fourth most populated country with a

land area close to 2 million km2 and a population of around 260

million people. It is estimated that Indonesia has about 120

million land parcels of which about one third are registered and

only about half of these are spatially identified. About 3

million new parcels appear each year.

Land administration in Indonesia is divided between

forestlands, administered by the Ministry of Environment and

Forestry (MoEF), and non-forest lands, administered by the

Ministry for Agrarian and Spatial Planning (BPN). This results

in duplication of policy, legal and institutional frameworks,

and precipitates unclear tenure arrangements and legal

recognition. The dualism also contributes to the slow

recognition of customary (“adat”) communities’ rights on land

and hinders the government’s ability to optimize land use and

protect resources (World Bank, 2016).

The lack of a unified spatial framework has created multiple

conflicts between communities and other land users (ibid). In

response, the Government of Indonesia introduced the One Map

Policy (OMP) as an effort to establish a unified, agreed-upon,

reference set of geospatial data that inform decision-making at

the national and sub-national levels. The current OMP

methodology aims to produce 1:50,000 scale maps based on over 80

thematic datasets and with limited or no ground verification.

However, in order to identify reliably the land use and

occupancy at the district and village levels, the OMP also

supports village boundaries mapping by district governments at a

scale of 1:10,000 or larger upon need. Furthermore, the

President has set a target for registering 5 million land

parcels in 2017, 7 million in 2018 and 9 million in 2019. This

target can only be achieved using a FFP approach, even though

some resistance is voiced, especially from the National Land

Agency (BPN). Some preliminary piloting has already taken place,

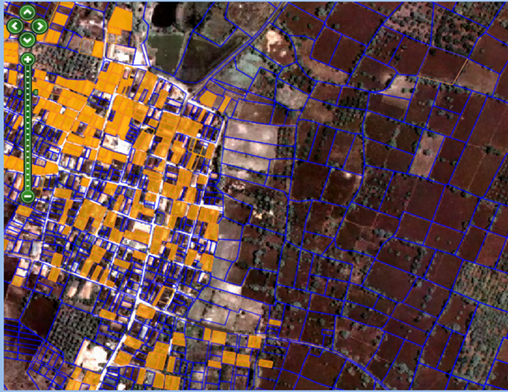

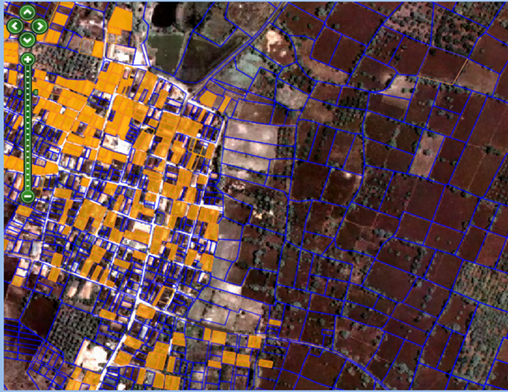

e.g. in Gresik District, East Java, see Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of demarcation of land parcels using high

resolution imagery.

Wotan Village, Gresik District, East Java Province, Indonesia

(Source: Gresik District Land Office)

Experience from this kind of FFP piloting looks very

promising, even though the legal & regulatory frameworks will

have to be adjusted in order to allow for mandatory registration

as part of the participatory process of boundary identification.

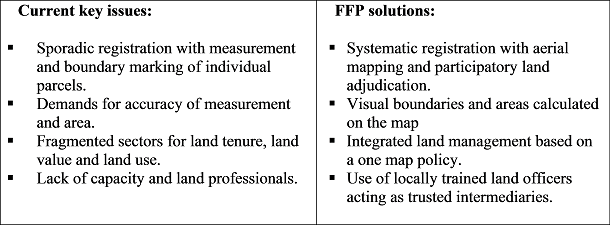

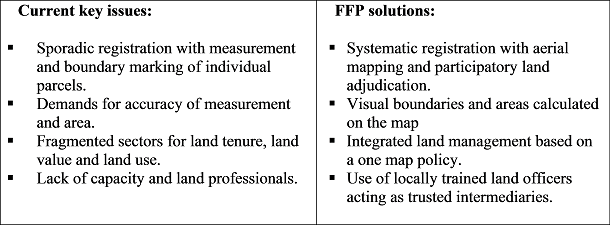

Overall, the benefits of implementing the FFP approach can be

summarised as shown in Table 2:

Table 2. FFP transition process in Indonesia.

The introduction of FFP land administration in Indonesia has

primarily been led and imposed on the institutions by the

President and driven by the priority land policy to introduce

security of tenure to support economic development. However,

success will depend on implementing institutional reform.

4.2 Nepal

The (then) Ministry of Land Reform and Management has been

working for a few years on developing a draft National Land

Policy. This policy aims to address the various land

administration and land reform issues that have remained

unresolved and under discussion for quite a long time in Nepal.

In Nepal, almost 28% of the total land area is arable and only

around 75 % of this is formally registered. The land

administration system does not deal with non-statutory or

informal land tenure. It is estimated that around 25% of the

total arable land and settlements are outside the formal

cadastre. This accounts for approximately 10 million parcels on

the ground, including occupied land parcels that legally belong

to either government, public or person/institution. This means

that a significant amount of the Nepalese population is living

in informality, without any spatial recognition and without

security of tenure.

The recent events, such as the mega earthquake of 2015 and post

disaster reconstruction and rehabilitation, the promulgation of

a new Constitution, and post conflict peace and social

rebuilding have ignited the need for developing a strategy for

implementation of the National Land Policy in the changed

context, see:

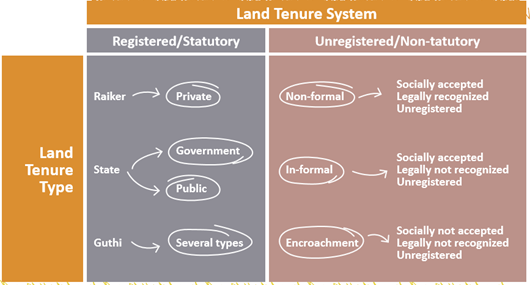

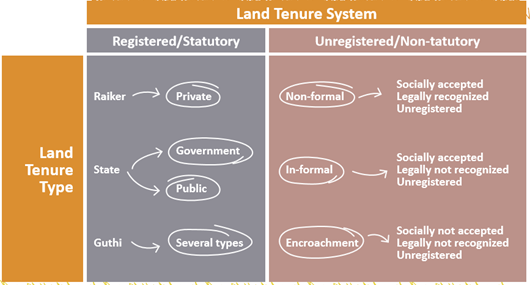

https://gltn.net/country-work/#nepal. The current Nepalese

land administration system (LAS) only deals with the formal or

statutory land tenure system, while there are three types of

non-statutory land tenure in the society: non-formal, in-formal

and encroachments, see Figure 5.

Figure 5. Tenure systems in Nepal (Source: Government of Nepal)

It is recognized that because of unsecured tenure, the settlers

hesitate to invest on the land to improve its productivity, and

without investment, production cannot be increased. All these

consequences show that the land under informal tenure is causing

huge loss to the economy and the valuable land asset is dumped

as “dead capital”, see Figure 6.

Figure 6. “Land administration is about people”. This family in

rural areas, about 20 km outside Kathmandu, has occupied a small

farm for four generations without any security of tenure to

enable investments and improvement of their livelihood (Photo:

Enemark, 2018).

Therefore, it was decided, in cooperation with UN-Habitat/GLTN

and Nepal civil society organisations, to develop an appropriate

strategy for implementing the latest provisions made in the

draft National Land Policy and the Constitution of Nepal. This

should ensure social justice on the one hand, and on the other

hand, lead to increased land productivity to support economic

growth. The strategy document integrates the resulting FFP

approach to land administration as a key solution to these

problems.

The strategy is strongly supported by government, including

Ministry of Agriculture, Land Management and the Survey

Department. Also, civil society organisations such as Community

Self Reliance Centre (CSRC) and the National Land Rights Forum

(NLRF) are very supportive, while some reluctance is voiced by

the professional land surveyors.

The draft strategy is currently (July 2018) under consideration

and adoption at the Parliament in Nepal, including a timescale

for implementation. The draft strategy document and an executive

summary is available at:

https://gltn.net/home/download/full-report-fit-for-purpose-land-administration-a-country-level-implementation-strategy-for-nepal/.

A summary report can be found at:

https://gltn.net/download/summary-report-fit-for-purpose-land-administration-a-country-level-implementation-strategy-for-nepal/.

4.3 Uganda

In Uganda, as in many Sub-Sahara African countries, colonial

governments introduced land administration systems to deal with

tenure insecurity. However, the tenure systems and procedures

for legal recognition of tenure rights were not oriented to the

context and realities of the African communities. The result is

that even after independence, many countries have only managed

to register less than 20% of their land.

The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda of 1995 (Chapter 15)

vests land in the citizens of Uganda hence giving powers to

citizens to own land privately as individuals, families or

communities. The 1995 constitution maintained the Freehold and

Leasehold tenure systems that were recognised under the colonial

laws. Furthermore, the 1995 constitution re-introduced the Mailo

Tenure system that is comparable to freehold, the difference

being the recognition of rights of occupants categorised under

the Land Act as bona fide or lawful. The constitution also

recognised customary tenure for the first time making it

possible for holders of customary rights in land to acquire

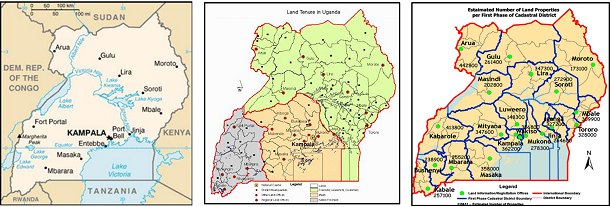

legal documents. Customary tenure accounts for approximately 80%

of land in Uganda see Figure 7.

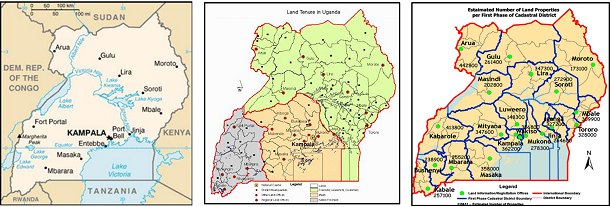

Figure 7. Left: Uganda, with a population of 28.3 million and an

area of 200.000 sq.km (excl. Lake Victoria waters), received

independence 1961 after 70 years of British colonization.

Middle: Land tenure in Uganda is divided between Native

freehold 22% (grey), Mailo 28% (yellow) and Customary 50%

(green). Right: Cadastral Information Branch Centres providing

local access to reliable land information. Source. Government of

Uganda.

Even though the Uganda Land Laws allow for registration of Mailo

(bona fide) titles and customary ownership (Certificate of

Customary Occupancy) these opportunities are not enforced in

practice. However, a number of recent pilot projects, carried

out by donors and civil society organisations, have introduced

the FFP concept as a vehicle for efficient and effective

systematic registration of land rights for the remaining about

20 million parcels currently outside the formal system. As the

challenges are enormous and the capacity of land stakeholders

limited, the Global Land Tool Network engages in Uganda to scale

up pro-poor land interventions in order to contribute to the

achievement of tenure security for all, see:

https://gltn.net/home/country-work/#uganda.

Figure 8. Left: Community people discussing the outcome of a

pilot project for registering land rights in the Mailo district

of Central Uganda. Right: A satellite imagery showing the mapped

parcel boundaries as demarcated though a participatory process

(Photo: Enemark, 2018).

The experiences of the pilot project are very promising and

well-received by government as well as at the community level.

Teams have been created, consisting a volunteer acting as

locally trained land officer and two representatives from local

government, to complete the parcel demarcation based on visual

boundaries as shown on large-scale satellite imagery or captured

in the field with hand held GPS.

The Government of Uganda has now engaged with UN-Habitat/GLTN to

develop a National Strategy for implementing a FFP approach to

land administration. The aim is to register 20 million parcels

within the next 10 years for a cost of around 10 USD per parcel.

This base cost does not include further costs relate to

institutional development, awareness raising and capacity

development.

The draft strategy presents the FFP concept and an assessment of

the current land administration system in terms of shortcomings

and constraints of delivering secure tenure for all. The

requirements for building the spatial, legal and institutional

framework is then presented along with the crosscutting issues,

such as capacity development and budgetary costs over a period

of 10 years. The draft strategy was recently (August 2018)

presented and discussed at a workshop with attendance of all the

key stakeholders and the final version is expected by the end of

September 2018 for further discussion and approval at Parliament

level.

The strategy is well supported at the Prime Minister level,

parts of the ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development,

and various civil society organisations. Some other stakeholder,

such as private licensed surveyors still voice some reservations

even though there is a growing understanding of relevance of

replacing costly field surveys with simple positioning at a

lower accuracy, supported by boundary corner plants. This also

relates to understanding the benefits deriving from a new role

as land professionals being the custodians of a countrywide land

administration system. Overall, the case of Uganda is very

interesting for testing the implementation of the FFP approach

at a national scale.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

There is a consensus that governing the people to land

relationship is at the heart of the 2030 global agenda. There is

an urgent need to build simple and basic systems using a

flexible and affordable approach to identify the way land is

occupied and used, whether these land rights are legal or

locally legitimate. The systems need to be simple and flexible

in terms of spatial identification, legal regulations and

institutional arrangements to meet the actual needs in society

today and they can then be incrementally improved over time.

Building such spatial, legal, and institutional frameworks will

establish the link and trust between people and land. This is

possible due to emerging, game changing technology developments

that enable mapping and registration procedures to be

undertaking at much simpler, cost efficient and participatory

ways. In turn, this will enable the management and monitoring of

improvements in meeting aims and objectives of adopted land

policies as well as meeting the global agenda. The results of

the current country implementations of FFP land administration

happening worldwide will make this approach compelling and

widely adopted. At last there will be a scalable land

administration solution implemented across the globe to

eliminate the scourge of insecurity of tenure. All land

professionals need to embrace and fully support this approach.

REFERENCES

Enemark, S., McLaren, R. and Lemmen, C. (2016): (2016):

Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration – Guiding Principles for

Country Implementation. UN-Habitat / GLTN, Nairobi, 120 p.

https://unhabitat.org/books/fit-for-purpose-land-administration-guiding-principles-for-country-implementation/

FIG/WB (2014): Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration. FIG

Publication No. 60.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/index.htm

UN (2014): The Millennium Development Goals Report 2014.

http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/mdg-report-2014.html

UN (2015): 2015 is the Time for Global Action.

http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

UN (2017): The Sustainable Development Goals report 2017.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/

UN-HABITAT/GLTN (2008): Secure Land Rights for All.

https://unhabitat.org/books/secure-land-rights-for-all/

World Bank (2016): Terms of Reference for Technical

Assistance and Capacity Development for the Program Preparation

to Operationalize and Accelerate the One Map Policy.

World Bank (2017): ‘New Technology and Emerging Trends: The

State of Play for Land Administration’. Washington DC, USA.

https://www.conftool.com/landandpoverty2018/index.php/14-07-McLaren-186_ppt.pdf?page=downloadPaper&filename=14-07-McLaren-186_ppt.pdf&form_id=186&form_index=2&form_version=finalNUn

(2017)

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Stig Enemark is Honorary President of the International

Federation of Surveyors, FIG (President 2007-2010). He is

Professor Emeritus of Land Management at Aalborg University,

Denmark. He is now working as an international consultant in

land administration and capacity development.

Email: enemark[at]land.aau.dk

Web:

http://personprofil.aau.dk/100037?lang=en

Robin McLaren is director of the independent consulting company

Know Edge Ltd, UK. He has supported many national governments in

formulating land reform programmes and National Spatial Data

Infrastructure (NSDI) strategies.

Email:

robin.mclaren[at]KnowEdge.com

Web: www.KnowEdge.com