Article of the Month -

June 2010

|

Climate Change and Sustainable Cities: Major Challenges

Facing

Cities and Urban Settlements in the Coming Decades

Dr. Mohamed EL-SIOUFI, Ph.D., Head, Shelter Branch,

United Nations Human Settlements Programme, UN-HABITAT

This article in .pdf-format (pdf,

190 kB)

This article in .pdf-format (pdf,

190 kB)

1) This paper has been presented as a keynote

presentation at the XXIV FIG Congress in Sydney 11-16 April 2010 in the

plenary session on The Big Challenges. Mohamed El Sioufi, Ph.D., is head

of the Shelter Branch at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme,

UN-HABITAT.

Handouts of this presentation as a .pdf file.

1. RAPID URBANISATION

Urban areas occupy only 2.8% of the earth’s surface yet as of 2008

more than 50% of the world’s population inhabits urban areas. Rapid

urbanization is occurring largely in developing countries where a

massive demographic shift has enormous implications in terms of poverty,

natural resources and the environment.

The ‘State of the World Cities Report’ published by UN-HABITAT in

2008 projects an average growth of 5 million new urban residents per

month in the developing world. In the coming decades, the developing

countries will be responsible for 95% of the world’s urban population

growth.

Levels of urbanization are expected to rise, with the least urbanized

regions of Asia and Africa transforming from largely rural societies to

predominantly urban regions during the course of this century. By 2050,

the urban population of the developing world will be 5.3 billion; Asia

alone will host 63% of the world’s urban population, or 3.3 billion

people.

Population growth and economic development cause drastic changes in

land use in many parts of the world and institutional arrangements need

serious reforming to ensure sustainable use of the increasingly scarce

land resources.

This paper will address the issues of climate change and sustainable

cities through an international perspective and scientific conceptual

framework followed by cities responses to mitigation and adaptation to

climate change. The paper will conclude with priority tools identified

by the Global Land Tool Network that are needed at country and city

level to address climate change challenges.

The ecological interaction of cities and their hinterlands is a

recurring theme. Rapid urbanization and climate change have given it new

impetus and sense of urgency. In 1976, the Habitat conference identified

“urban expansion” as a universal development challenge. At the Rio

Summit in 1992, the concept of “sustainable human settlements” was

introduced. At the Habitat II conference in 1996, the Habitat Agenda

highlighted the need for new approaches to planning and managing rapid

urban growth thus advancing the notion of “sustainable urbanization”.

The world has come a long way on the debate and discourse of these

issues. But the challenges are complex and daunting, and require

continuous engagement and effort at all levels. The climate change

phenomenon is making the issue of sustainable urbanization a matter of

urgency.

Climate change is now recognized as one of the most pressing global

issues of our planet. It is no coincidence that global climate change

has become a leading international development issue at the same time as

the world has become urbanized. The way we plan, manage, operate and

consume energy in our cities will have a critical role in our quest to

reverse climate change and its impact.

2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

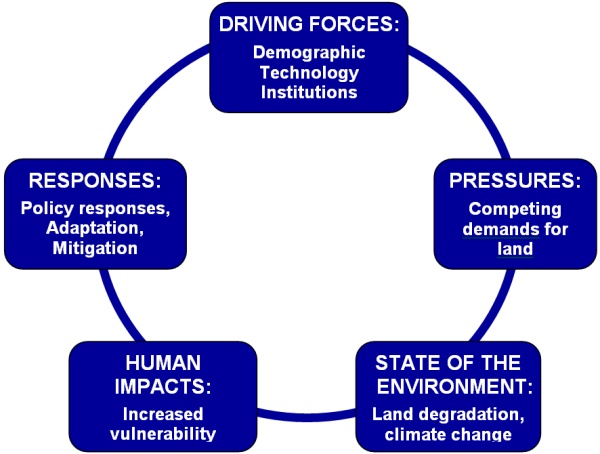

Recently, the Global land Tool Network (GLTN, UN-HABITAT) undertook a

study on “Land, Environment and Climate Change: Challenges, Responses

and Tools”. The study builds on existing UN-HABITAT work; various

researches undertaken in the areas of land, environmental and climate

change; and through an e-discussion in 2009. It uses the Driving

Force-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DFPSIR) framework as a basic

element of the conceptual framework.

It is important to understand the causes behind environmental

degradation in order to identify suitable responses. The DFPSIR

framework can serve as a simple interdisciplinary starting point. It

should then be broadened to capture essential elements of the

functioning of socio-environmental systems where institutions guide

resource utilization and protect and enhance human welfare. Property

rights are core determinants for how land resources are utilized and

their welfare effects are distributed. Similarly, the degree of market

development for natural resources as inputs in production and as

essential elements of livelihoods and safety nets for current and future

generations determine the need for complementary non-market institutions

and regulations where markets do not work properly.

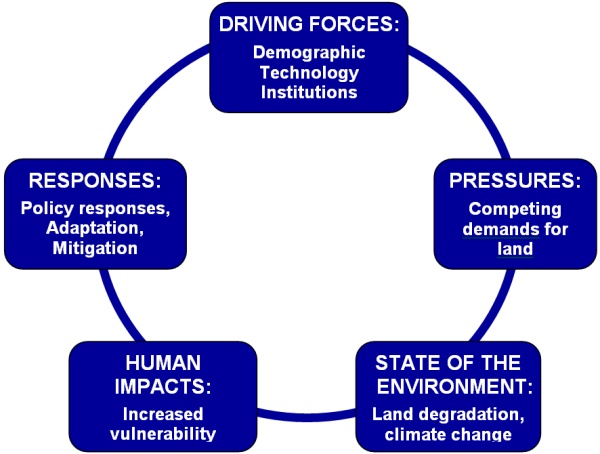

Figure 1: Driving

Force-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DFPSIR) conceptual framework

There are five components of the DFPSIR framework:

- Driving Forces are underlying in form of population

growth, technology and changes, institutional (political, market,

cultural, social), structures, and changes. Land laws and markets

affect land resources through how they impact on land management.

There are typically nested interactions among these driving forces.

- Pressures from the driving forces have direct impacts on

the environment. These include forest clearing for agricultural

production, city growth on agricultural land, or pollution of land,

water and air from industrial, and other human activities. Pressures

emerge from the incentive structures created by the driving forces.

- The State of the Environment can be captured by assessing

the stock of natural resources, changes in them or environmental

quality indicators like, erosion levels, nutrient stocks, soil

quality, pollution levels, changes in areas or quantities of carbon,

and loss of species or habitats. Global warming due to GHG emissions

causes changes in air and water temperatures, sea level rise and

severity of storms, floods, and droughts.

- Human Impacts of the changes in the environment are

measured through a range of indicators, like poverty status, food

security or other measures of vulnerability, access to land and

resources, tenure security, market access, access to shelter and

other basic human needs, access to safety nets, and the degree of

empowerment or political influence. At aggregate level these are

related to the Millennium Development Goals.

- Responses include responses at local, national and

international levels. They can address the Driving Forces, the

Pressures, the Environment or Human Well-being. The time perspective

may also vary from short- to long-term.

Urban areas also have several of the same types of land-related

environmental problems with soil, water and air pollution as the most

severe urban problems in many developing countries. The severity of

these land-related environmental problems varies greatly across

locations and so does the vulnerability of the people living in the

different locations to the effects of these environmental problems. The

severity of the effects can also be delayed till certain threshold

levels of degradation or accumulation have been passed and may therefore

be ignored or underestimated by current populations while future

generations will be badly affected. This is particularly the case for

global warming where those who have caused the problem are more able to

protect themselves than those who are most severely affected by climate

shocks and sea level rise due to climate change.

3. MAIN ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES RELATED TO LAND

The main environmental challenges related to land identified in the

recent study by GLTN/UN-HABITAT include:

Unequal land distribution

- Geographical poverty-environment traps.

- Increasing land fragmentation in densely populated

areas.

- Unequal land distribution, land degradation and

inefficient land use

- Unsustainable management including increased activity in

land rental markets and short-term strategies on rented

land.

- Threat by elite capture undermining land reforms.

International efforts are important to enhance the

transparency and accountability in situations where the poor

loose out. |

60% of Nairobi’s population lives on 5% of the city’s area |

Tenure

- Tenure insecurity in relation to urban expansion

- Tenure insecurity for poor slum dwellers in developing countries

- Tenure insecurity undermining investment and leading to

environmental mismanagement in urban and rural areas.

- Threats against flexible tenure systems in pastoral and

agro-pastoral areas

- Increasing pressures on customary tenure systems that are in

need of revisions.

Only 30% of plots are registered in developing countries and 2-3% of

the land is owned by women in Sub-Saharan Africa. The continuum of land

rights proposed by the GLTN is an important milestone in addressing

tenure security issues.

Figure 2 - Continuum of land tenure rights

Land use

- Encroachment of agriculture in particularly vulnerable and

valuable habitats.

- Deforestation and forest degradation leading to carbon

emissions, loss of biodiversity and mud slides.

- Environmental damage in “frontier” areas for new energy sources

- Sharp increases in demands for land for food and bio-fuel

production displacing the poor.

Seventy-five percent of commercial energy is consumed in urban and

peri-urban areas. In addition, 80% of all waste is generated from our

cities and up to 60% of Greenhouse Gas Emissions which cause global

climate change emanate from cities.

Recent large-scale land deals in Africa and Asia in response to rising

biofuel demand and resulting food price increases is an area where

international organizations can help poor countries and local people in

the negotiations to develop contracts that protect their interests.

Establishing better standards for transparency and accountability and

increased international pressures and support to implement such

standards will be important to reduce levels of corruption and elite

capture.

Climate change

- Increasing threats in coastal areas due to sea water rise and

severe weather risk.

- Increasing threats to human settlements in coastal areas and

islands

- Increased probability of droughts and erratic rainfall due to

climate change

There have been recently warnings that the sea level is rising twice

as fast as was forecasted, threatening hundreds of millions of people

living in deltas, low-lying areas and small island states. But the

threat of sea-level rise to cities is only one piece of the puzzle. More

extreme weather patterns such as intense storms are another. Tropical

cyclones and storms, in the past two years alone, have affected some 120

million people around the world, mostly in developing and least

developed countries. Indeed, in some parts of the world, inland flooding

is occurring more often and on a more intense basis.

We are witnessing more frequent flooding and drought in the same

year, causing heavy impact on food security, energy and water supply.

This is practically daily occurrence for many of the world’s less

fortunate people who live in life-threatening slums. For them, the

climate is already out of control and, perhaps equally important, out of

comprehension.

We are witnessing more frequent flooding and drought in the same

year, causing heavy impact on food security, energy and water supply.

This is practically daily occurrence for many of the world’s less

fortunate people who live in life-threatening slums. For them, the

climate is already out of control and, perhaps equally important, out of

comprehension.

The impacts of climate change will be felt strongly in the years to

come. If sea levels rise by just one meter, many major coastal cities

will be under threat: Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles, New

York, Lagos, Alexandria, Egypt, Mumbai, Kolkata, Dhaka, Shanghai,

Osaka-Kobe and Tokyo, just to mention some mega cities that are under

imminent threat.

The many smaller coastal cities, especially those in developing

countries and those of small island nations will suffer most due to

their limited adaptation options. More and more people are drawn to the

urban magnet. In many parts of the world, climate refugees from rural

areas that have been hit by drought or flooding aggravate the migration

to cities. Those parts of the population who already suffer from poor

health conditions, unemployment or social exclusion are rendered more

vulnerable to the effects of climate change and tend to migrate to

cities within or outside their countries. The UN predicts that there

will be millions of environmental migrants by 2020, and climate change

is one of the major drivers.

Therefore, there is no doubt that climate change exacerbates existing

social, economic and environmental problems, while bringing on new

challenges. The most affected today, and in future, will be the world’s

urban poor – and chief among them, the estimated 1 billion slum

dwellers.

Our studies have identified important research gaps and key research

questions related to land, environment and climate change challenges,

seeking to explore ways to empower all who are working in these areas to

overcome them.

4. THE ROLE OF CITIES IN MITIGATION

It is crucial to recognize that cities and urban residents are not

just victims of climate change but also as part of the problem. If

cities are part of the problem, that means they must also be part of any

solution.

Mitigation measures are urgently required. However, and to date, the

measures envisaged globally and nationally have yet to be accompanied by

concerted measures at the city and local levels. While we fine-tune

carbon trading instruments, we need to take immediate actions to make

our cities more sustainable by revisiting our land-use plans, our

transport modalities, and our building designs. There is a unique

opportunity to bridge our global efforts in emissions control with local

efforts to improve the quality of life and the productivity of our

cities. Our cities are, after all, the driving force of our economies,

and what better measures can be take than to reduce traffic congestion,

improve air and water quality, and reduce our ecological footprint.

In this regard, urban density is a key factor. A recent survey

indicated that in New York City, per capita greenhouse gas emissions are

among the lowest in the United States. This is because less energy is

needed to heat, light, cool and fuel buildings in this compact city

where more than 70 percent of the population commutes by public transit.

The city of Atlanta in the USA and Barcelona Spain, for example, both

have a population of about 2.5 million. Atlanta currently occupies an

area of 4200 sq km whereas Barcelona occupies only 162 sq km. Atlanta

consumes much more energy due to its urban form and higher per capita

energy consumption.

Climate change mitigation can be a good business opportunity. Clean,

low-carbon infrastructure investments, retrofitting of buildings, the

renewal of our transport systems are opportunities for ‘green’

investments. According to the estimates of international associations of

local governments, already 2800 cities have committed themselves to

reducing their annual GHG emissions, or meeting other targets for more

sustainable urban development. While most of these cities are in the

Global North, others in the South are taking specific measures taken to

reduce urban emissions include construction of an urban wastewater

methane gas capture project, undertaken in Santa Cruz (Bolivia); energy

efficiency audits of municipal buildings by Cape Town (South Africa);

and development of rapid transport systems and other measures designed

to reduce the use of single occupancy vehicles in a number of cities.

5. THE ROLE OF CITIES IN ADAPTATION

At the same time, there is rising consensus that cities must take

immediate adaptation measures to reduce vulnerability. Here again, we

have yet to recognize the need to plan our cities and settlements to

prevent loss and destruction of lives and properties. The time to act is

now and the place to act is in the cities of the world. Cities not only

have to take preventative measure, they must plan to offset the worst.

In this respect, there is no doubt that local authorities will be the

front line actors in finding local answers to these global challenges.

There is no one-size fit all solutions and each local authority will

have to assess its own risks and vulnerability and plan accordingly.

It is obvious that local authorities, especially secondary cities in

developing countries that are growing the fastest, will be the most

severely tested by these challenges. These cities, despite their rapid

growth, contribute a minimal share to global greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet they are the cities that are most at risk in terms of suffering the

impacts of climate change.

Cities can adapt to the impacts of climate change via effective urban

management. Planning and land use controls can prevent people from

building in zones at risk of flooding and landslides (e.g., restrictions

on building within 50 year floodplains in South Africa). Guidelines and

regulations, such as a decision issued by the Thua Thien Hue provincial

authorities in Vietnam to encourage cyclone-resistant building

practices, can increase resiliency and make economic sense.

However, we also know that many cities in Least Developed Countries

do not have much urban infrastructure assets that can be adapted.

Therefore, adaptation can not be disconnected from the need for local

development. Both adaptation and mitigation strategies in urban areas

require new and improved infrastructure and basic services. This

provides cities in developed and developing countries with unique

opportunities to redress existing deficiencies in housing, urban

infrastructure and services and to create jobs and a new opportunities

to stimulate the urban economy.

The resolve with which the cities stuck to their climate action

despite the current economic crisis was very reassuring. They remain

convinced that climate change action makes economic sense. For example,

increased energy efficiency is not only good for the climate but also

makes sense for a city's budget. As former president Bill Clinton said:

"For every 1 billion US dollars invested in the retrofitting of houses

to increase their energy efficiency, 6000 jobs are created. This is six

times bigger in impact than in average public investments. And what is

more: savings in energy will pay back for this investment in just over 7

years".

6. THE CITIES IN CLIMATE CHANGE INITIATIVE

The technologies are there. The solutions exist. They range from

water harvesting to solar energy, and from affordable mass transit to

bio-fuel production. But turning the huge unmet needs into market demand

requires the right mix of political will and commitment, well-founded

policies and strategies, an enabling business environment and capacity

development.

It is in this context and in response to these challenges that

UN-Habitat has launched the Cities in Climate Change Initiative.

This initiative is supporting the efforts of government agencies and

local authorities in adopting more holistic and participatory approaches

to urban environmental planning and management, and the harnessing of

ecologically sound technologies. The Initiative uses adaptation as a

starting point to engage people, their local authorities and the private

sector in risk abatement action.

This starting point leads to mitigation. Here, the Cities in Climate

Change Initiative argues that the measures required for adaptation and

mitigation are the same, namely better land use planning, better urban

management, more participatory governance focusing on more resilient

housing and smarter infrastructure and basic services.

The Cities in Climate Change Initiative has started off last year in

four pilot countries of Mozambique, Uganda, Philippines and Ecuador. It

has since expanded to cities in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Namibia, Rwanda and

Senegal. We are currently starting assessments in several Asian

countries and we are fundraising to respond to the strong interest from

Small Island Developing States in the Pacific and the Caribbean.

UN-HABITAT provides capacity building support and helps ensure the

sharing and transfer of knowledge and lessons learned from experience.

We have received new mandates by our Governing Council to support cities

in addressing Climate Change more forcefully.

In partnership with the Cities Alliance, the World Bank and the

United Nations Environment Programme, UN-Habitat is refining methods to

support cities to measure their climate footprint and assess their

climate change vulnerability. These metrics should assist cities in

accessing climate related finance.

7. KEY PRIORITIES AND PROMISING LAND TOOLS OF THE GLOBAL LAND TOOL

NETWORK (GLTN)

To focus more on land and climate change issues, UN-HABITAT has

participated in the setting up of a Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) and

assuming the role of technical secretariat for the Network. GLTN

includes an international partnership of key actors on land. Many of you

are already members in this network through your professional

organizations including FIG, UN sister agencies such as FAO. UN-HABITAT

are among other prominent actors including development IFIs such as the

WB; Donors (Sida and Norway); technical agencies (GTZ); INGOs (the

Huairou Commission, SDI, Hajimani); academia (Harvard University,

University of East London); and others. The rich variety of

complementing partners in the network illustrate a maturity and

realization of all of us acknowledging the need to cross our specialized

boundaries in a quest to better define and understand the issues on the

ground as well as to jointly agree on priority gaps to be addressed to

better guide us all in our work.

The GLTN together with our other programmes focus on issues related

to cities and urban areas. Issues identified include land and governance

with FAO; gender valuation with the Huairou Commission and FIG; Social

Tenure Domain Model (STDM) with FIG, ITC and WB; Land Tenure and Natural

Resource Governance in Africa with US-Aid and development partners in

Kenya; Development of Natural Disaster Guidelines on Land - Land issues

with humanitarian partners; and Land, Environment and Climate Change:

Challenges, Responses and Tools- together with a Norwegian Research

Institution.

GLTN has identified key priority areas where land stakeholders could

add value as well as develop land tools that could be used to enhance

sustainable land management and human well-being. The Global Land Tool

Network (GLTN) has identified key priority and promising land tools:

- Land tenure reform: Land reform requires thorough

analysis of each country’s specific situation and must be widely

agreed upon by various interest groups in the land sector. Taxing of

land values was identified as a crucial instrument to mobilize idle

land and make it available to more efficient and needy users.

However, even though introducing such a tax system seems an optimal

solution, there can be strong political constraints as it is likely

to be opposed by landowners and the elite. The best strategy would

be to look at the range of land relation taxation solutions. In a

broader urban perspective on policies and tools there are many

examples of innovative, pragmatic and cost effective policies to

improve access, land tenure security and property rights for the

urban poor. Information on these is already in the public domain.

- Land rights records and registration: low-cost land

registration and certification

- Land use planning: low-cost, participatory land use

planning and mapping

- Regulation of land markets to enhance sustainable land use:

land market regulations have been and are still common in many

countries. Concerns about environmental consequences may call for

regulation of land rental markets, [for example when] rental

contracts are of short duration. Short-duration contracts can

suppress investment incentives, leading to non-sustainable land

management practices.

- Land management, administration and information:

accessible to all in a transparent way with focus on climate change

mitigation and adaptation issues.

- Slum rehabilitation and resettlement including provision

of tenure security in urban slums. Forced displacement of slum

dwellers without adequate alternatives, resettlement options or

compensations is the recipe for further social, economic and

environment losses. Displaced urban dwellers tend to resettle on

more marginal and vulnerable sites. Their source of and access to

livelihoods are often severely undermined. Upgrading and

reconstructing degraded urban environments such as slums is crucial

in combination with providing good alternative resettlement areas.

Development of low-cost and incremental approaches is key due to the

budgetary restrictions and the large and growing number of slum

dwellers. More importantly, preventing and containing slum growth,

especially on vulnerable landscapes would provide long-term gains.

- Land law, regulation and enforcement: land laws are

crucial tools for enhancing more sustainable land use. However, land

laws can also be ‘toothless’ unless enforced. Development of

improved land laws needs parallel dissemination of information about

the content of the laws in the land administration system as well as

other parts of national and local administrations that have an

influence on land use (e.g. Ministries and Departments of energy,

forestry, agriculture, transportation, and planning). Furthermore,

the public and land users themselves need to be informed.

Universities and relevant education programs, research institutions,

land user organizations, NGOs, and large private enterprises are all

organizations that should help disseminate such information. In

developing countries with poor information access and low levels of

literacy, it takes years before the contents of new land laws reach

land users, if ever, before new laws are passed. The language of the

laws is hard to understand for people with limited formal education.

The new laws have to be translated into local languages before being

disseminated. Popular formats conveying the essence of the law may

be more suitable for dissemination than direct translations.

- Payment for environmental services: Design of Payment for

Environmental Service (PES) schemes as a way to create markets for

resources that are threatened by degradation and consequently also

for their maintenance and improvement, can become important policy

tools in the future. However, this requires innovative designs and

careful pilot testing before they are scaled up. The poverty of land

users and the poverty reduction effects of PES schemes will be

important design considerations.

- Payment for resource dividends: A progressive land and

resource dividend system, if introduced, may mobilize idle land from

large land and resource owners for more efficient use in countries

with unequal land and resource distribution. However, to succeed it

is crucial to frame such a dividend system in a palatable way to

build sufficient public support for its introduction. GLTN can take

a leading role in piloting and promoting the use and scaling up of

such land tools.

- Participatory public works programs / productive safety nets

and as means to invest in environmental conservation:

rehabilitation and conservation of community facilities (e.g.,

roads, drainage networks, waste disposal systems, etc) can be

undertaken using food for work or cash for work program. These can

not only help healthy and better serviced neighborhoods, but also

create opportunities for gainful employment.

- Collective action for enhancement of environmental services:

[Formal and public sector based] Law, regulations and law

enforcement mechanisms are not enough in most countries. More

important is consolidated and coordinated action for ensuring

quality and standard of urban environmental services. A strong urban

environment monitoring agency is essential. An independent, powerful

and capable urban environment protection force can be established.

- Integrated rural and urban development: rural development

and urban development are closely linked through migration, flow of

resources, economic empowerment, commodities and services. The

problem of expanding slums cannot therefore be seen as exclusively

an urban problem as they are largely filled by immigrants from rural

areas. Slums may be compared to a leaking boat: new migrants flow in

as earlier slum dwellers are rehabilitated or moved elsewhere. The

problem can only be tackled at a broader scale requiring both rural

and urban development.

- Providing tenure security and slum rehabilitation:

Increasing populations in urban areas makes is making it difficult

to provide shelter and security of tenure for urban dwellers,

especially for the poor and other vulnerable groups. Poorly managed

rapid urban population growth in developing countries often leads to

a rapid growth of slums and increasing environmental health

problems. Severe environmental degradation is one of the common

features in developing country cities. Insecure tenure in informal

(often illegal) settlements makes it also unattractive for poor

households to invest in improving their temporary housing

arrangements and adopt sustainable environmental practices.

Conventional titling programs in such urban areas have often failed

to solve many of the basic problems and may have forced poor slum

dwellers to relocate in environmentally risk-prone and hazardous

locations, further exposing them to natural disasters. It appears

that legal pluralism is preferable, combining ownership-based and

rights-based approaches while taking into account the needs of the

poor, their financial constraints and the limited capacity of urban

land administrations. This also implies a continuum of land rights,

including freehold tenure, leasing arrangements, public ownership,

group tenure, and informal tenure arrangements (Payne et al., 2008).

Many alternative approaches to titling are being tested. Examples of

these are:

- Provision of temporary occupational licenses, group

ownership by community land trusts, and company or co-operative

ownership and subdivision of land to members in Kenya.

- Simple documentation of informal settlements in Egypt.

- Cooperative housing in South Africa.

- Provision of Certificate of Rights to use and develop state

owned land in Botswana.

- Temporary land rental in Thailand.

- Recognition of illegal settlements in Indonesia.

- Relocation of illegal settlers by providing land titles on

nearby land in Cambodia.

- Provision of registered leaseholds in squatter settlements

in Brazil.

- Formal landlord-tenant property contracts in Bolivia (Dey et

al., 2006).

- Rescue plans for areas threatened by sea level rise and storm

floods: Particularly vulnerable areas with large poor

populations that are unable to protect themselves against sea level

rise and storm floods need international and national support.

Whether it is most appropriate to invest to protect their current

livelihoods or to organize resettlement in safer locations depend on

the relative costs of the alternative solutions. This will depend on

the expected size of the necessary protective barriers that have to

be built for protection, the distance to available alternative

locations for resettlement, the size of the population, costs of

building suitable resettlements, etc. A long-term plan for gradual

resettlement is preferable to an after-disaster resettlement. The

latter will be more chaotic and will involve severe losses. In

relation to such planned gradual resettlement, there are important

property rights issues to be resolved. The property value of the

properties lost may fall significantly but there is also a risk that

evacuated areas and houses are likely to be occupied by

opportunistic settlers. …. The financial costs will be very high and

clearly beyond what poor affected populations, communities, cities

and countries can afford. Since the cause of the problem is also

global, it is necessary to develop an international system for

funding of such large-scale operations. This is an area where UN

agencies could play an important role. Support will also be needed

for building professional capacity to tackle such large resettlement

schemes. Organizing a network of professional staff from threatened

countries and cities is an important first step.

8. CONCLUSION

To meet the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) goal 7, target 11 to

have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100

million slum dwellers by 2020, is a central concern of UN-HABITAT. This

target must be seen in connection with the factors causing rapid inflow

of new migrants as well as the fact that some of these areas are in

coastal zones that are threatened by sea water rise and weather risk.

Rural development and land reforms in rural areas can contribute to

reduce the inflow of people and therefore be an important part of the

solution. Similarly, rural development can be seen as one of the means

of alleviating poverty and increasing incomes for both rural and urban

people. At the same time it must be an international responsibility,

particularly for the countries that have contributed most to carbon

emissions to provide funds for adequate compensation and alternative

livelihoods for the people that are threatened by sea water rise,

drought or flooding due to climate change. UN agencies can continue to

take a leading role in the planning of strategies to tackle this

problem.

The world is at a cross roads; the fight to combat poverty and

climate change is to be won or lost in our cities. Cities, as much as

they embody the challenges also offer the solutions. The hundreds of

communities and cities whom we recognize for their good practices

symbolize this potential. The challenge is that many cities in the

developing world are not endowed with the capacity to harness and

mobilize knowledge.

A sustainable city must be a learning city which is continuously

exploring and innovating, sharing and networking. Universities and

knowledge centres have much to contribute to this endeavour.

Universities bring their knowledge and expertise, whilst cities offer

them unique opportunities to link research and education with policy and

practice. Recognizing this potential, UN-HABITAT, has recently launched

the World Urban Campaign to harness and channel knowledge, expertise and

experience in support of sustainable urbanisation.

Finally, the challenges facing cities with regard to climate change

are numerous and daunting, and no entity, public or private,

governmental or non-governmental, academic or practitioner, can face

these challenges alone. All those who are committed to turning ideas

into action are invited to join UN-HABITAT and its partners in the quest

for more sustainable urban development.

BIOGRAPHY

Dr. Mohamed El-Sioufi is the Head of the Shelter Branch

in UN-HABITAT. He has 32 years of experience in architecture, housing

and urban planning. His experience bridges professional practice,

academia, research, training and technical advice. He has worked for

UN-HABITAT since 1995 in training and capacity building, policy and

technical cooperation and the development of global norms and

guidelines. His experience in human settlement spans a variety of

specialized fields including capacity building in sustainable urban

development including historic cores, housing policy and strategies,

slum upgrading, climate change mitigation through sustainable building

materials and construction technologies, post disaster rehabilitation,

environmental planning and management.

CONTACT

Dr. Mohamed El-Sioufi

Head, Shelter Branch

UN-HABITAT

00100 Nairobi

KENYA

Mohamed.El-Sioufi@unhabitat.org

|