| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 47

Institutional and Organisational Development

A Guide for Managers

Contents

Foreword

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 How to use this guide

2. The Context

2.1 Capacity, capacity building and sustainable organisations

2.2 Land administration

2.3 Institutional and organisational development

3. A Checklist for Managers

4. Necessary Components in Sustainable

Organisations

4.1 The necessary components

4.2 Make clear statements defining the responsibilities of each

level/ sector

4.3 Provide transparent leadership ‘from the top’ to encourage

collaboration in both top-down and bottom-up ways

4.4 Define clear roles for the different sectors, including the

private sector

4.5 Establish a clear organisational culture that supports a

cooperative approach amongst individual employees

4.6 Ensure that the network of individuals and organisations has

a sufficient voice with key decision makers for land administration issues to be

taken fully into account in all central policy making

4.7 Facilitate policy development and implementation as a process

that is open to all stakeholders, with all voices being clearly heard

4.8 Provide a legal framework that enables the use of modern

techniques and cross-sector working

4.9 Offer relevant training courses that clearly explain,

encourage and enable cooperative and action-based working by organisations,

within a clearly understood framework of the roles of each level/ sector

4.10 Share experiences through structured methods for learning

from each others’ expertise and experiences, with this learning fed back into

organisational learning

References and Bibliography

Orders for printed copies

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) believes that

effectively functioning land administration systems are of central

importance to ongoing economic development. These systems provide guarantees

of land tenure which enable economic activity and development. There are

many elements to land administration systems, and many organisations

involved in both the public and private sector. As with any chain, the

system is only as strong as its weakest part.

It is therefore appropriate that FIG, as the leading

Non-Governmental Organisation representing surveyors and land administrators,

has set as its central focus for the 2007–2010 period the task of ‘Building the

Capacity’. This requires capacity assessment and capacity development, both of

which are vital to building sustainable capacity.

This publication is the result of a FIG Task Force on

Institutional and Organisational Development leading to a guide for managers to

build sustainable institutions and organisations.

FIG has committed itself and its members to further progress in

building institutional and organisational capacity to support effective land

administration systems. Such work is particularly about developments at the

organisational level, but this cannot ignore the societal and individual levels.

Progress requires honest self-assessment of organisational and system strengths

and weaknesses. Effective management action must follow, to build on the

strengths and address the weaknesses.

FIG commits itself to support managers and professionals in this

task, working with governments, national bodies and individuals. This guide

provides a tool in this regard.

The document builds on several other FIG Publications, including

the Bathurst Declaration (FIG, 1999); the Nairobi Statement on Spatial

Information for Sustainable Development (FIG, 2002a); Business Matters for

Professionals (FIG, 2002b); the Aguascalientes Statement (FIG, 2005); and

Capacity Assessment in Land Administration (FIG, 2008).

This work would not have been possible without the contribution

of the Task Force members – Santiago Borrero, Richard Wonnacott, Teo Chee Hai,

Spike Boydell and John Parker – as well as many other individuals who have

reviewed, commented on and improved draft outputs, completed questionnaires and

the like. FIG is very grateful to all of them.

Stig Enemark

FIG President |

Iain Greenway

FIG Vice President

Task Force Chair |

1. Introduction

Effectively functioning land administration systems, providing guarantees of

land tenure, are of central importance to ongoing economic development. In many

countries, however, land administration systems are not sufficiently robust to

deliver effective land tenure, and this can limit or restrict economic

development. This impacts the global economy, as well as the economy and the

welfare of the citizens of the country involved.

1.1 Background

The FIG Task Force on Institutional and Organisational Development has taken

forward a programme of work to assess the particular challenges to building

organisational capacity. The Task Force developed, tested and refined a

self-assessment questionnaire to determine capacity at system, organisation and

individual levels; this was made available to and completed by professionals

from many countries. In reviewing the responses to the questionnaire, FIG also

considered other recent work including that of the UN FAO (2007), AusAID (2008)

and Land Equity International (2008). This work (which is described in more

detail in Greenway (2009)) led FIG to draw the following broad conclusions:

- cooperation between organisations is a weak point: there is often

suspicion rather than cooperation;

- the remits and skills of the different organisations involved in

administering a land administration system are often not joined up

effectively;

- the lack of effective working across sectors is a particular issue;

- there are skill gaps, particularly in the conversion of policy into

programmes, the division of labour, and ensuring effective learning and

development;

- stakeholder requirements appear insufficiently understood or

insufficiently balanced, leading to ineffective use of outputs;

- there is insufficient time and effort given to learning from past

experience.

These key findings led FIG to the view that a number of key components need

particularly to be considered by those who want to build sustainable

institutional and organisational capacity in land information systems – these

components are described in this publication.

1.2 How to use this guide

This publication is written for use by practitioners. It aims to provide

individuals and organisations with an increased understanding of capacity

building, in particular building the capacity of organisations to meet the

increasing demands placed on them. In this way, it complements FIG Publication

41 – Capacity Assessment in Land Administration (FIG, 2008), which considers the

capacity of the system.

The essence of the publication is the checklist for managers at Section 3.

This is developed further in Section 4, which draws together the key lessons

from FIG’s work and experience and presents them in the form of key issues which

must be addressed, along with examples from around the world.

Section 2 provides context for the challenges of institutional and

organisational development, including defining some of the terms used.

A possible use of this document by a practitioner anxious to review, and as

necessary improve, the capacity of an organisation is:

- read Section 2 of this document to make sure that terms and definitions

are clearly understood;

- consider the checklist at Section 3 to determine particular areas for

development, focussing on the developmental areas highlighted by the

self-assessment tool;

- use the material in Section 4 as a basis for focusing improvement

activity.

Land registration office, Uganda.

2. The Context

This section provides some background to the issues of capacity building and

land administration, to ensure that users of this publication have a clear

understanding of the terms used.

2.1 Capacity, capacity building and

sustainable organisations

UNDP (1998) offers this basic definition of capacity: “Capacity can be

defined as the ability of individuals and organizations or organizational units

to perform functions effectively, efficiently and sustainably.” UNDP (1997) has

also provided the following definition of capacity development: “the process by

which individuals, organisations, institutions and societies develop abilities

(individually and collectively) to perform functions, solve problems and set and

achieve objectives.”

Capacity building consists of the key components of capacity assessment and

capacity development. Sufficient capacity needs to exist at three levels: a

societal (systemic) level; an organisational level; and an individual level,

with all three needing to be in place for capacity to have been developed.

So what is a sustainable organisation? From these definitions, it is one

which:

- performs its functions effectively and efficiently;

- has the capability to meet the demands placed on it; and

- continuously builds its capacity and capability so that it can respond

to future challenges.

Such an organisation needs to assess its capacity honestly and objectively,

and to give focused attention to capacity development. The emphasis on

sustainability is vital: unless capacity is sustainable, an organisation cannot

respond effectively to the ongoing demands placed on it.

2.2 Land administration

Land administration is a central part of the infrastructure that supports

good land management. The term Land Administration refers to the processes of

recording and disseminating information about the ownership, value and use of

land and its associated resources. Such processes include the determination of

property rights and other attributes of the land that relate to its value and

use, the survey and general description of these, their detailed documentation,

and the provision of relevant information in support of land markets. Land

administration is concerned with four principal and interdependent commodities –

the tenure, value, use, and development of the land – within the overall context

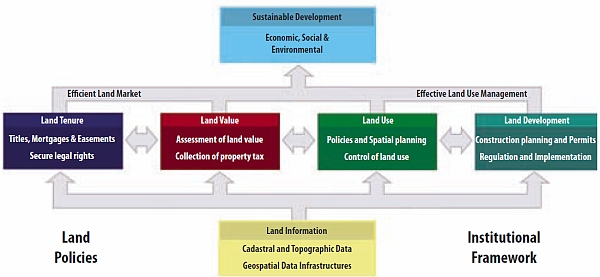

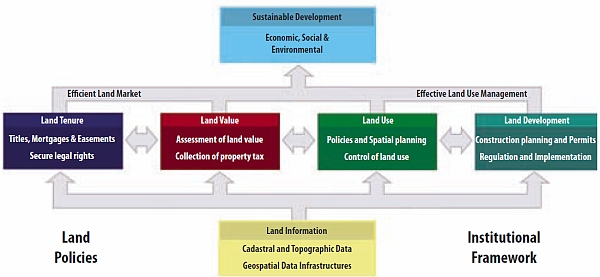

of land resource management. Figure 1 below depicts how these elements link

together to provide a sustainable land administration system.

Figure 1: A Global Land Administration Perspective

(Enemark, 2004).

The day to day operation and management of the four land administration

elements involves national agencies, regional and local authorities, and the

private sector in terms of, for instance, surveying and mapping companies. The

functions include:

- the allocation and security of rights in lands; the geodetic surveys and

topographic mapping; the legal surveys to determine parcel boundaries; the

transfer of property or use from one party to another through sale or lease;

- the assessment of the value of land and properties; the gathering of

revenues through taxation;

- the control of land use through adoption of planning policies and land

use regulations at national, regional and local levels; and

- the building of new physical infrastructure; the implementation of

construction planning and change of land use through planning permission and

granting of permits.

The importance of capacity development in surveying and land administration

at the organisational level was usefully quantified in Great Britain (OXERA,

1999) by research that found that approximately £100 billion of Great Britain’s

GDP (12.5% of total national GDP, and one thousand times the turnover of OSGB)

relied on the activity of Ordnance Survey of Great Britain. With such very

significant numbers, as well as the central importance of sound land management,

the need for sustainable and effective organisations in the field of surveying

and land administration is clear.

2.3 Institutional and organisational

development

For the purposes of this document, institutional development relates to the

enhancement of the capacity of national surveying, mapping, land registration

and spatial information agencies and private organisations to perform their key

functions effectively, efficiently and sustainably. This requires clear, stable

remits for the organisations being provided by government and other

stakeholders; these remits being enshrined in appropriate legislation or

regulation; and appropriate mechanisms for dealing with short-comings in

fulfilling the remits (due to individual or organisational failure). Putting

these elements in place requires agreement between a wide range of stakeholders,

in both the public and private sectors, and is a non-trivial task.

Organisational development, in contrast, relates to the enhancement of

organisational structures and responsibilities, and the interaction with other

entities, stakeholders, and clients, to meet the agreed remits. This requires

adequate, suitable resourcing (in staffing and cash terms); a clear and

appropriate organisational focus (to meet the agreed remit of the organisation);

and suitable mechanisms to turn the focus into delivery in practice (these

mechanisms including organisational structures, definition of individual roles,

and instructions for completing the various activities).

Figure 2: A Performance Management Model (HMT, 2000).

One useful and succinct model for putting in place suitable measures to

enable and underpin organisational success is that developed by the UK Public

Services Productivity Panel (HMT, 2000). This recognises five key elements which

need to be in place:

Of course, defining and implementing the detail in any one of the above items

is a significant task, and all must be in place if the organisation is to

succeed. By putting the appropriate mechanisms and measures in place, and

continuously challenging and improving them, organisations can ensure that they

effectively turn inputs into outputs and, more importantly, the required

outcomes (such as certainty of land tenure).

All organisations need continuously to develop and improve if they are to

meet, and continue to meet, the needs of their customers and stakeholders. In

the land administration field, there are many examples of under-resourced

organisations unable to respond effectively to stakeholder requirements, thereby

leading to a lack of access to official surveys and land titling (leading to

unofficial mechanisms being used, or a total breakdown in efficient land

titling). There is a need to provide appropriate assistance to enable the

necessary capacity to be built and sustained by such organisations, given the

key role of their operations in underpinning national development. A range of

methods exist, including releasing internal resources for this work (if suitable

resources exist), or external support.

3. A Checklist for Managers

Managers and leaders need to give a strong focus to the following nine issues

if they are to develop sustainable institutions and organisations. Some key

questions to consider are provided below; more detail is provided in sections

4.2–4.10.

1. Make clear statements defining the responsibilities of each level/

sector

- Are you clear what the role of your organisation is in the land

administration process and how it interacts with that of other

organisations?

- Are you clear on the roles and responsibilities of the other

organisations with which you need to interact?

- Are your staff clear?

- Do other organisations and stakeholders agree your understanding of

roles and responsibilities?

- Does the division of responsibilities enable effective delivery of land

administration functions?

- Does legislation support this division of responsibilities?

2. Provide transparent leadership ‘from the top’ to encourage

collaboration in both top-down and bottom-up ways

- Do you, as a manager within the land administration system, understand

the extent of the end-to-end processes involved in the system?

- Do you appreciate the benefits that can be delivered by those involved

in the entire process working together effectively?

- Are you assessed on the overall effectiveness of the land administration

system for your jurisdiction and its citizens?

- Do you give a clear lead, in word and action, to your staff to work to

improve the effectiveness of the overall system?

- Are the necessary informal and formal agreements in place between

organisations to support cross-organisation working?

- Is there the necessary culture of working together to support

cross-organisation working?

3. Define clear roles for the different sectors, including the private

sector

- Do you have a clear understanding of the current roles of the different

sectors – public, private, academic – in the land administration system?

- Is the allocation of roles clear and objective?

- Does the allocation of roles support the effective operation of the land

administration system?

- Is the allocation of roles agreed with leaders of all sectors?

- Is the allocation of roles kept under review and adjusted as necessary?

4. Establish a clear organisational culture that supports a cooperative

approach amongst individual employees

- Do your words and your actions consistently reinforce the need for

joined up collaborative working throughout your organisation and with other

relevant organisations?

- Do your organisation’s key targets explicitly include elements that can

only be delivered with input from other organisations?

- Is staff performance measured with reference to the overall success of

the land administration system?

- Are the successes you report internally and externally related to the

need to deliver overall system goals?

5. Ensure that the network of individuals and organisations has a

sufficient voice with key decision makers for land administration issues to be

taken fully into account in all central policy making

- Does your organisation have strong and effective links with policy

makers?

- Do these links give you a voice that is heard in the policy development

process?

- Does the policy development and maintenance process sufficiently

recognise operational realities?

- Are the links sufficiently formalised that they will survive changes of

key individuals?

6. Facilitate policy development and implementation as a process that is

open to all stakeholders, with all voices being clearly heard

- Does policy making on land administration matters in your jurisdiction

take place in a way that ensures that the voices of all stakeholders are

heard?

- Do stakeholders have confidence in the fairness and robustness of the

policy making process, so that they can accept the results?

- Do professionals play a key role in commenting on and shaping policy

development?

7. Provide a legal framework that enables the use of modern techniques and

cross-sector working

- Does the law covering the land administration system provide a clear

framework of requirements whilst avoiding stipulating inputs and methods?

- Does the law appropriately recognise the reality of different types and

formality of tenure?

- Are the various types of law, regulation and instruction used

appropriately to address issues of principle, policy and procedure?

8. Offer relevant training courses that clearly explain, encourage and

enable cooperative and action-based working by organisations, within a clearly

understood framework of the roles of each level/ sector

- Do education and training courses for surveyors reflect the reality of

professional practice?

- Are training courses regularly reviewed with key input from practising

professionals?

- Are staff from your organisation invited to participate in other

organisations’ training courses – and do staff from other organisations

participate in your organisation’s training courses – to assist in the

spread of information and in building relationships?

- Do training courses provide students with a clear overview of the entire

land administration system and the various organisations involved, before

providing detailed education in particular components of it?

- Do training courses include examples of successful collaborative working

between organisations and individuals?

9. Share experiences through structured methods for learning from each

others’ expertise and experiences, with this learning fed back into

organisational learning

- Do you complete a structured learning process with those involved at the

end of a project?

- Do you share the results of this learning with others who might benefit

from it now or in the future?

- Do you use web-based systems to share and gain learning?

4. Necessary Components in Sustainable

Organisations

Section 2 has provided a general description of land administration, a

general model for organisational development and a description of a sustainable

organisation. This Section provides a description of nine key elements which

FIG’s work leads it to believe need to be present for such an organisation to

exist, and which (from FIG’s research) are often not in place. It includes

examples of where they have been successfully implemented in different countries

and states.

4.1 The necessary components

FIG considers that managers and leaders need to give a strong focus to the

following nine issues if they are to develop sustainable institutions and

organisations:

- Make clear statements defining the responsibilities of each level/

sector.

- Provide transparent leadership ‘from the top’ to encourage collaboration

in both top-down and bottom-up ways.

- Define clear roles for the different sectors, including the private

sector.

- Establish a clear organisational culture that supports a cooperative

approach amongst individual employees

- Ensure that the network of individuals and organisations has a

sufficient voice with key decision makers for land administration issues to

be taken fully into account in all central policy making.

- Facilitate policy development and implementation as a process that is

open to all stakeholders, with all voices being clearly heard.

- Provide a legal framework that enables the use of modern techniques and

cross sector working.

- Offer relevant training courses that clearly explain, encourage and

enable cooperative and action-based working by organisations, within a

clearly understood framework of the roles of each level/ sector.

- Share experiences through structured methods for learning from each

others’ expertise and experiences, with this learning fed back into

organisational learning.

These statements cover all five elements of the performance management model

illustrated in Figure 2.

The following sections elaborate on each of the nine issues, providing

further description and giving examples of work that has been done in the

relevant area. The sections are intended to assist managers of organisations

seeking to increase sustainable capacity. The sections should generally be used

following completion of a self-assessment questionnaire to determine particular

areas of concern, or used directly by managers familiar with their

organisations. Section 3 has summarised the questions connected to each issue.

4.2 Make clear statements defining the

responsibilities of each level/ sector

Land administration is a far-reaching aspect of government activity and many

different organisations are involved in policy development and the delivery of

its different elements. This often includes organisations at supra-national,

national, regional and local level. Many aspects of the work will be laid down

in formal legislation, but much of this legislation will focus on the work of

particular organisations or parts of the system.

Other elements of the system will rely on informal understandings or ‘custom

and practice’. Given this situation, many stakeholders will be confused as to

who does what, meaning, for instance, that:

- politicians will expect things of certain organisations when they are

the responsibility of other organisations;

- citizens will contact the wrong organisations; and

- staff in organisations will be unclear of their role and interactions,

and will not know which other organisations to contact.

All of this will lead to confusion, frustration, delay and wasted activity.

In a truly sustainable system, each organisation involved in land

administration knows what its role is – and what it isn’t – and which other

organisations it needs to work with to deliver overall objectives. This is clear

to stakeholders – politicians, land owners and occupiers, private sector firms,

citizens, staff – meaning that the right work is done in the right places. This

in turn means that scarce resources aren’t wasted on correcting confusion and

that the agreed goals of the land administration system are delivered more

effectively.

|

Australia has three levels of government – national, state and local.

Australia’s constitution gives responsibility for land-related matters

to the states: for instance, all land registries are the

responsibilities of the states. Working through a range of committees

and councils with representation from different levels of government, it

has been possible to develop a collaborative model. For mapping, it has

been agreed that the national mapping organisations will be responsible

for small scale mapping of the country (smaller than 1:100,000); and

states will be responsible for medium and large-scale mapping (1:50,000

and larger). For example, in the State of Victoria, there are defined

responsibilities and roles established with local government bodies and

some regional authorities as to whether they will undertake large scale

mapping or provide data elements to the state which then becomes the

custodian of that data on behalf of the local government body or

authority. In this way, the responsibilities of all levels of government

are clear – and those responsibilities have been shared between

different levels of government in an effective way. Information

provided by a Task Force member |

|

In Europe, the INSPIRE Directive (http://inspire.jrc.ec.europa.eu/

) provides a legal framework for consistent management of spatial data

throughout the 27 member states of the European Union. This is designed

to ensure that data analysis and use is effective. Previously, analysis

of major river systems required data from several countries to be joined

together, raising difficulties with inconsistencies in data formats,

terminology, coordinate reference systems and the like. Data

collection and management remains a national function, but the Directive

requires clear responsibility for the maintenance of different datasets

to be allocated, metadata about the datasets to be available in a

consistent format in geoportals, and the technical elements of data

sharing to conform to international standards. In this way, data can be

shared more effectively, reducing duplication of effort, ensuring that

data is fit for the required purpose, and allowing better decisions to

be made more quickly.

Information provided by a Task Force member |

Key questions:

- Are you clear what the role of your organisation is in the land

administration process and how it interacts with that of other

organisations?

- Are you clear on the roles and responsibilities of the other

organisations with which you need to interact?

- Are your staff clear?

- Do other organisations and stakeholders agree your understanding of

roles and responsibilities?

- Does the division of responsibilities enable effective delivery of land

administration functions?

- Does legislation support this division of responsibilities?

If the answer to any of these questions is ‘no’, engagement with other

organisations and/or law makers, along with clear, improved communication is

essential.

In general, written descriptions of roles and responsibilities, presented in

easy to understand ways (such as flowcharts showing who is responsible for the

different activities) will allow the identification of unclear areas, overlaps

and gaps, at which stage dialogue can address and resolve the issues.

Changing the law takes time, but a focus on clear written agreements of who

does what will allow earlier resolution of issues. The Australian example above

shows how a State government and local government have agreed a sensible

allocation of responsibilities so that, collectively, they fulfil legal and user

requirements effectively.

4.3 Provide transparent leadership ‘from the

top’ to encourage collaboration in both top-down and bottom-up ways

Many different organisations are involved in land administration. There is an

understandable tendency for each organisation to set targets and priorities

based around its own activities. This provides staff, managers and stakeholders

of that organisation with assurance that it is working efficiently and

effectively. Such an approach, however, can limit the overall effectiveness of

the system.

|

Property valuation activities can increasingly be completed from data

derived from aerial photography and satellite imagery, improving the

efficiency of the data collection and valuation processes and removing

the time-consuming need for ground inspections. Such ground inspections,

however, enable the data collectors to gather the ownership and date

information essential for property tax administration. Organisations

which oversee the end-to-end process, therefore, often require the

retention of ground visits in the valuation process, as this improves

the overall effectiveness of the tax assessment and collection process.

|

In a truly sustainable system, the various organisations involved in the land

administration system work together to agree shared objectives which improve

overall system efficiency. This is challenging work for managers, who may often

be assessed and rewarded based on the efficiency of their organisation. This

emphasis on end-to-end effectiveness therefore needs to be reinforced by clear

messages and actions from governments and administrations, to make clear that

such joining up is both required and expected. Such joining up may include

consideration of organisational mergers, but it is important to remember that

organisations do not necessarily need to merge to be able to work together

effectively. Often more important is a clear demonstration by managers and

leaders that they understand and want to use the benefits of formal and informal

collaboration. This may include the putting in place of Service Level Agreements

or other agreements between organisations. This top down demonstration,

complemented by appropriate target setting, gives staff in the different

organisations the confidence to think widely about the opportunities for overall

system improvement, and to work together to deliver this.

|

In Northern Ireland, work on a Geographic Information (GI) Strategy for

the province began in 2001 with the bringing together of key experts and

stakeholders for a three-day structured process of agreeing key

priorities. This led to the publication of a strategy and the setting up

of a cross-sectoral Steering Group, with sectoral groups drawn of

individuals from different organisations progressing proof of concept

studies (including one which cut the time taken for utility companies to

ascertain what other cables and pipes were under a road ‘from six weeks

to six minutes’). Centrally, the Steering Group also oversaw the

development of a GeoPortal, GeoHub NI™ (www.geohubni.gov.uk).

In 2008, the Steering Group agreed that the key elements of the strategy

had been completed, and an inclusive process which included workshops,

blogs and formal Ministerial approval, led to the publication of a new

Northern Ireland GI Strategy for 2009-19

http://www.gistrategyni.gov.uk)

which has been approved by the Ministerial Executive[cabinet].

Implementation is being managed by a cross-sectoral Delivery Board,

guided by a GI Council of very senior officials and managers from the

public and private sectors. Information provided by a Task Force

member |

Key questions:

- Do you, as a manager within the land administration system, understand

the extent of the end-to-end processes involved in the system?

- Do you appreciate the benefits that can be delivered by those involved

in the entire process working together effectively?

- Are you assessed on the overall effectiveness of the land administration

system for your jurisdiction and its citizens?

- Do you give a clear lead, in word and action, to your staff to work to

improve the effectiveness of the overall system?

- Are the necessary informal and formal agreements between organisations

in place to support cross-organisation working?

- Is there the necessary culture of working together to support

cross-organisation working?

If the answer to any of these questions is ‘no’, it is vital that you gain a

wider understanding of the land administration system and engage with other

senior managers to demonstrate the very real performance benefits of

cross-organisational working.

The benefits of working collaboratively throughout the land administration

system are well documented. Your work can therefore often start with looking at

experiences in other jurisdictions, and proposing pilot projects to demonstrate

real benefits, and that they can be delivered in a reasonable time and for a

reasonable cost. In this way, stakeholder resistance, based on concerns that the

operation of the system will be disrupted by the effort to join up more, can be

reduced.

The Northern Ireland example shows how the bringing together of stakeholders

started by structured work in a neutral environment. The benefits of

collaboration are now sufficiently well understood in Northern Ireland that such

structures and safeguards can be relaxed.

4.4 Define clear roles for the different

sectors, including the private sector

Because of its fundamental importance to economic and national development,

the land administration system – and most of its components – is in most

jurisdictions managed and operated by the government. Ultimately, the task of

allocating roles rests with government as the custodian – on behalf of the

citizen – of an effective land administration system.

In many jurisdictions, the private sector delivers key elements of the land

administration system. The role of government in allocating responsibilities and

tasks, however, can lead to the private sector feeling that it is seen as

secondary by the public sector.

The academic sector is also pivotal in maintaining sustainable capacity: it

is this sector which designs and delivers training courses – both at the start

of people’s careers and, increasingly, in lifelong learning. These courses must

deliver the required information, and set the required culture of effective

collaboration. Otherwise, the professionals involved in the land administration

system will not receive clear and unambiguous messages about their role in the

wider system.

In a truly sustainable system, government (on behalf of citizens) retains

overall responsibility for the land administration system. It engages with

representatives of all of the other sectors involved to agree each sector’s

roles and responsibilities. The government then allocates roles and tasks

between sectors in the most effective manner, and keeps this under review to

ensure that changes in capacity and capability lead to adjustment of allocations

as appropriate.

The government may choose to document the roles of the different sectors in

legislation, or may choose to provide clear statements on a non-legal basis. It

then acts in accordance with these statements, including when considering

governmental support in its different forms.

|

In New Zealand, the legal mandate for administering the central

components of the land administration system rests with the public

sector, in particular the government agency Land Information New

Zealand. All public sector organisations, however, outsource their land

surveying work. This has been a longstanding practice in cadastral

surveys, where licensed surveyors complete surveys which are ratified by

the Surveyor General and then lodged in the central government database

(currently known as Landonline). Private sector surveyors therefore hold

invaluable information about the practical impacts of legislation and

regulations and, individually and collectively (for instance, through a

professional body such as the New Zealand Institute of Surveyors),

provide key practitioner input to ensuring workable regulations which

enable effective and timely surveys by suitably skilled practitioners.

The public sector policy makers recognise that individuals and

organisations in the private sector are key stakeholders – and work with

them on an as-needed basis and through the professional bodies whom they

view as key allies in the continuous drive for improvement and increased

effectiveness. Information provided to a Task Force member

|

|

Professionals working in hydrographic surveying and nautical charting

operate within a framework of national and international law. It is

therefore important that the training of Hydrographic Surveyors properly

reflects changes in the law and in technology. Given the important

international elements, the International Hydrographic Organisation

(IHO) has a lead responsibility for regulating and certifying

Hydrographic Surveying courses. IHO also recognises the important

expertise of practising professionals. It has therefore, together with

FIG, formed an International Board for the Standards of Competence of

Hydrographic Surveyors and Nautical Cartographers that includes

representatives of FIG and the International Cartographic Association

(ICA). It is this International Board that decides on the recognised

standard of Hydrographic Surveying and Cartography courses.

The Board also reviews formal continuing professional development

schemes and arrangements for Hydrographic Surveyors seeking recognition

at international level. The International Board is therefore a good

example of governments, professionals and academia working together to

ensure effective professional development.

Information provided to a Task Force member |

Key questions:

- – Do you have a clear understanding of the current roles of the

different sectors – public, private, academic – in the land administration

system?

- Is the allocation of roles clear and objective?

- Does the allocation of roles support the effective operation of the land

administration system?

- Is the allocation of roles agreed with leaders of all sectors?

- Is the allocation of roles kept under review and adjusted as necessary?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, the work of the different

sectors involved in the land administration system is likely to be ineffectively

organised.

A number of forums will probably already exist for discussion of effective

allocation of activity. Professionals in the public, private and academic

sectors will probably all be members of the relevant professional body, for

instance. This will enable peer-to-peer discussions of the current arrangements

and how they can be improved. The professional body is likely to have contact

with professional bodies in other jurisdictions, allowing a comparison of

arrangements across countries.

This information can be collated and proposals for effective allocation

drafted for discussion. Wide engagement at an early stage will be essential, and

careful positioning of the work to ensure that it is seen as driven by concerns

of public policy and not a sectional group (section 3.6 is also relevant in this

regard).

The IHO example above shows how sectors within a community can collaborate

effectively, each respecting the role and responsibilities of the others, to put

in place and sustain an effective way of working.

4.5 Establish a clear organisational culture

that supports a cooperative approach amongst individual employees

Within an organisation, managers may state that working across and beyond the

organisation is important. But if staff performance is assessed on their

individual effectiveness in their particular role, collaborative working will

not develop in practice.

In a truly sustainable system, words, actions and systems all fully support a

cooperative approach to activity, both across teams and business units within an

organisation, and between organisations.

The key influence on the approach taken in practice is the organisational

culture – that unspoken, unwritten understanding of ‘the way we do things round

here’. Elements that need to be considered in the organisational culture

include: the way that people are rewarded (for individual performance or for

team effort); the symbols that are used (the success stories reported in formal

publications, the news in staff briefings, even the pictures in the office

reception area). And all of this needs to be continuously reinforced by all

levels of managers in their words and their actions – for instance, that

managers of organisations are seen to meet regularly together to agree

inter-organisation liaison.

|

In many countries, a variety of organisations have been created and set

apart from central government – for instance, as Government Owned

Companies, Commercial State Bodies and the like. In some countries, they

have been moved out of the capital city for reasons of regional balance.

It then requires specific effort to make sure that the organisations

work effectively together, treating each other as customers and

suppliers or, even more effectively, as partners in a joint venture to

make the best possible land administration system. In a number of

countries, the organisations responsible for mapping, valuation and land

registration have been brought together into single organisations by

governments which have recognised the benefits of close working. This

has happened, for instance, in many Australian states, in the Caribbean

and in Northern Ireland. Organisational mergers are not essential –

collaborative working is very possible between organisations – but they

provide a very clear statement that the different organisations rely on

each other to deliver the outcomes required from the land administration

system. Information provided by Task Force members |

|

In Land & Property Services in Northern Ireland (www.lpsni.gov.uk),

the key organisational targets are set using a balanced score card

approach. A Management Committee of managers from all directorates meets

monthly to review progress against all of the organisation’s key

targets, and to reassign resources and funding between targets as

necessary to ensure ongoing balance between them. This process

recognises that all areas of the business have a key role to play in the

achievement of corporate objectives, and that such decisions can in many

cases be taken by managers without needing the intervention of Board

members. Information provided by a Task Force member |

Key questions:

- Do your words and your actions consistently reinforce the need for

joined up collaborative working throughout your organisation and with other

relevant organisations?

- Do your organisation’s key targets explicitly include elements that can

only be delivered with input from other organisations?

- Is staff performance measured with reference to the overall success of

the land administration system?

- Are the successes you report internally and externally related to the

need to deliver overall system goals?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, your actions and your words

will not encourage and cajole staff to work together across and beyond

organisational boundaries. You will therefore need to consider how your actions

can support such collaborative working. Actions speak louder than words –

informal contacts and/or formal agreements with other organisations will provide

a clear framework for collaboration. Shared targets will link this approach into

organisational and individual success measures. And the successes that you

choose to highlight can further reinforce this.

Mergers are one organisational solution to the challenges of working across

organisational boundaries. Committees are another. Both have been summarised in

the examples in this section.

4.6 Ensure that the network of individuals and

organisations has a sufficient voice with key decision makers for land

administration issues to be taken fully into account in all central policy

making

Many organisations are involved in delivering an effective land

administration system. These organisations may be working, individually and

collectively, very effectively. However, it is also important that the legal and

policy framework in place fully supports operational delivery, and that the

framework is sufficiently responsive to political, economic, social and

technological changes to enable sustainable development.

In many countries, policy making and operational delivery are seen as

distinct activities with limited communication between them. This is likely to

lead to policy that is not grounded in practical reality, and operational

delivery which is constrained (and sometimes impossible) because of

inappropriate policy. Excellent social policy objectives will not be delivered

if the proposed implementation is cumbersome or unworkable.

In a truly sustainable system, policy making and operational delivery are

seen as parts of the same activity, with constant communication and iteration

between the two parts to ensure that policy meets the needs of the government

and its citizens, but that the policy can be faithfully and completely

delivered. It is therefore essential that policy makers receive and take fully

into account the constructive, well-articulated views of operational delivery

staff and vice versa. Policy makers receive very many representations to

introduce, adapt or repeal policy. It is therefore vital that those responsible

for delivering the land administration system – in the public and the private

sectors – speak with a strong, coherent voice, and use a variety of channels to

influence the policy makers.

|

In the Netherlands, the development of law, policy and operational

aspects of the spatial planning aspects of a National Spatial Data

Infrastructure (SDI) has taken place in a collaborative manner. It has

involved three levels of government – national, provincial and

municipal. The 2006 Spatial Planning Law was driven largely by planning

considerations, but its reliance on SDI was quickly seen and the Law was

drafted to provide a sound legal basis for the SDI. Regulations created

under the Law provide a specific legal basis for the SDI. Considerable

collaboration also took place in the development of standards to support

the operation of the SDI. A top level project group consisting of

representatives of municipalities, provinces, several departments of

central government, delivery organisations and lawyers managed the work,

setting up separate research groups of experts as required. The

standards will now be reviewed on a 2-yearly basis, in a process managed

by Geonovum, the Dutch geographic standardisation foundation. This will

be done in close collaboration with the main spatial planning

stakeholders, in a transparent process, to ensure commitment and

effectiveness. Information summarised from Duindam et al, 2009,

supplemented by discussions with a Task Force member |

|

The creation of a standardised core tenure model has long been discussed

by land administration professionals and international agencies of the

UN. There was general agreement that such an international model would

be valuable, whilst recognising the different legal systems and

processes in different countries. Both the policy makers and the

professionals recognised that they would not be able to create an

effective model separately, so a process of collaborative working

involving UN-HABITAT and FIG was agreed. This involved stakeholder

discussions and expert workshops to create a draft Social Tenure Domain

Model (STDM) of particular relevance to developing countries. This has

been formally reviewed for UN-HABITAT by FIG. A more generally

applicable model, the Land Administration Domain Model (LADM), has also

been developed by FIG experts, and is now being taken forward through

the broad consensus process of ISO to create an international standard,

which is expected to be complete by 2011. The ISO process has brought

together experts from public, private and academic sectors. All involved

agree that the resulting document is much stronger than would have been

possible without this collaboration.

Information provided to a Task Force member by the Project Leader of

the LADM work in ISO. |

Key questions:

- Does your organisation have strong and effective links with policy

makers?

- Do these links give you a voice that is heard in the policy development

process?

- Does the policy development and maintenance process sufficiently

recognise operational realities?

- Are the links sufficiently formalised that they will survive changes of

key individuals?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, there are real risks that

policy will not develop and adapt to allow effective delivery. You need to

ensure that policy makers hear the voice of the delivery organisations, and

respect it as an important, objective voice.

This may most effectively begin through making personal contacts, and through

showing where specific, straight forward changes can make a real difference.

Through this process, the benefits of policy and operations working together

will become clear and can be communicated on the basis of examples. Further

formalisation can then be put in place to be able to withstand the moving on of

key individuals.

Working in this way delivers better results, and completes the process more

quickly despite the slower start as engagement is put in place. The Netherlands

have found this, as has the international community, in the examples above.

4.7 Facilitate policy development and

implementation as a process that is open to all stakeholders, with all voices

being clearly heard

It is important that those developing policy for land administration, and

those delivering the land administration system, clearly hear other voices.

Individual citizens are key stakeholders in the system and have to believe that

the system delivers equitably and effectively. Pressure groups also need to have

their voices clearly heard and taken into account.

The primary role for ensuring this breadth of engagement lies with policy

makers. A key secondary role, however, lies with the delivery organisations and

individuals, who will engage with individual citizens and community groups on a

daily basis in their work. Such individuals need to ensure that such input is

provided to the policy makers.

This also applies to the development of organisational strategies for

individual organisations. Citizens and representative groups need to be

convinced that their voices are all heard and taken seriously if they are to

feel any ownership of the resulting decisions. Consultation and feedback are

critical if successful strategies are to be developed.

If stakeholders do not believe that their voices are heard and respected,

they will not have confidence in the land administration system and will use

other routes to seek to change decisions that have been made.

In a truly sustainable system, all voices are heard and priorities are agreed

based on all of the voices. Communication and feedback explains why certain

ideas cannot be taken forward, so that all stakeholders understand and are able

to support policy and organisational strategy.

|

Recent FIG Commission 9 consideration of compulsory land acquisition has

found that using the compulsory process is considerably less effective

in reaching agreement and acceptance of stakeholders than the use of

voluntary methods. Voluntary methods must be formulated to ensure that

all stakeholders have a clear voice, and are heard. If all stakeholders

understand that a compulsory process will follow unless the matter can

be resolved by agreement, this will focus everyone’s minds, but makes it

vital that the procedures and professionals involved in the voluntary

process ensure that all stakeholders have their voices heard fairly, and

that the reasons for the ultimate decision are clearly explained.

Information provided to a Task Force member |

|

Prior to 1994 (when South Africa became a fully democratic nation), land

ownership was generally restricted to the white population. Some groups

were forced out of the areas in which they had stayed for many years,

and moved to other areas for various political reasons. Since 1994, the

forced removal of communities and individuals and the return of those

communities to their original homes or land has taken up a great deal of

the time and energy of the Land Claims Commission. For example, a

certain area close to the centre of Cape Town has had an unfortunate

history of delay (over seven years) in finalizing the return of

forcefully removed communities to the area, with little progress having

being made because not all of the community interest groups were

included in the negotiations from the very start of the process. There

has also been a history of acrimony between municipal, provincial and

state bodies which has had strong political undertones and has not aided

the process. The Commission has found that, in order to make any

progress in these matters, it is important to be very sensitive to the

needs of all groupings, irrespective of political affiliation or

interest, and to involve all groups from the earliest stages of policy

making. Information provided by a Task Force member

|

Key questions:

- Does policy making on land administration matters in your jurisdiction

take place in a way that ensures that the voices of all stakeholders are

heard?

- Do stakeholders have confidence in the fairness and robustness of the

policy making process, so that they can accept the results?

- Do professionals play a key role in commenting on and shaping policy

development?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, stakeholders are unlikely to

feel fully engaged in the policy development process and will therefore feel

limited ownership of its outcomes. Professionals have a key role to play in

improving this process, as they engage with many stakeholders on a regular

basis, and are perceived as being interested, expert and objective, meaning that

they can speak with the confidence that other stakeholders may not have.

It is therefore important that professionals build strong connections with

the policy making and shaping process. This will often start through personal

links, allowing professionals to show the policy makers and other stakeholders

the value they can bring to the process.

The South African example above shows the difficulties that can arise when

insufficient consultation and communication takes place.

4.8 Provide a legal framework that enables the

use of modern techniques and cross-sector working

Legal frameworks develop over time and take a good deal of time and effort to

alter. Legislative capacity is generally restricted, with many pressures for

parliamentary time. This means that many countries rely on relatively old

legislation to control the land administration system. That in itself is not a

problem; the problem arises if the legislation prescribes details of the work to

be completed.

Legislation is also the highest authority in any jurisdiction, providing the

legal framework within which all citizens and organisations must operate. It is

therefore important that the law does not restrict or hinder cross-sector

working, and is managed in a flexible way so that it can adjust to changes in

society and technology.

In a truly sustainable system, the necessary constraints of the law making

process and timetable are fully recognised, and laws focus on required outcomes.

Inputs such as technical matters which change on a regular basis, are managed

through regulations or instructions under the authority of the law but which can

be changed in a more flexible (but transparent and accountable) manner.

|

If legislation states that angles must be measured a set number of times

when completing various elements of cadastral surveys this, by its very

wording, means that GPS surveys cannot be used because a GPS survey

cannot be shown to conform to the legislation. If the law were to state,

by contrast, that the final accuracy of coordinated survey points in the

cadastre is to be x centimetres, the Surveyor General or equivalent

could stipulate any requirements in regulations and instructions as he

or she sees appropriate and necessary; and these regulations could be

altered more rapidly. Similarly, many countries are now considering

moving (or have moved) to coordinated cadastres without survey marks. If

legislation prescribes the form and nature of survey marks, it will need

to be altered, delaying the possibility of implementing marker-less

cadastres. But if the legislation states that corner points must be

recoverable on the ground with an accuracy of y centimetres, the

Surveyor General or equivalent can state what is and is not allowable.

In the state of Victoria, Australia, the Survey Cadastral Regulations and the

Survey Coordination Regulations used to be quite prescriptive, for instance

detailing how boundaries should be traversed and measured. The latest

regulations are non-prescriptive and leave it to the surveyor to determine how

s/he obtains the accuracy required. The surveyor must be able to demonstrate how

s/he has verified that the survey meets the required accuracy.

Information provided by Task Force members |

Land and land tenure are emotive and politically sensitive issues in

most African countries. In Botswana, there are three categories of land

inherited from colonial rule: Customary land, Stateland and Freehold

land. The allocation and administration of each category is different.

Most people are resident on Customary land, so it is imperative that the

administration of this land is well guided to secure and

sustain people’s livelihoods.The Botswanan Government took early

steps after independence, with the 1968 Tribal Land Act which created

Land Boards to administer customary land and introduced leasehold

arrangements in customary land. The Act was amended in 1993 to keep pace

with social and economic changes. The Land Boards were put in place to

improve customary land administration, ensure that emerging economic

opportunities were adequately catered for in Botswana’s land management

system, create capacity for handling the demanding and complex land use

issues emanating from the new economic opportunities, and democratise

customary land administration.

The national land policy was reviewed in 2002 to ensure that it was capable

of addressing current challenges. The land policy is considered to have been

successful, with much of that success achieved because the policy has addressed

the following factors:

- cultural beliefs and practices;

- consultation and democracy;

- political and economic stability;

- population size;

- ongoing review of critical issues.

Summarised from Mathuba, 2003 |

Key questions:

- Does the law covering the land administration system provide a clear

framework of requirements whilst avoiding stipulating inputs and methods?

- Does the law appropriately recognise the reality of different types and

formality of tenure?

- Are the various types of law, regulation and instruction used

appropriately to address issues of principle, policy and procedure?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, the legal system is unlikely

to facilitate the effective operation of the land administration system. It will

therefore be important that professionals and delivery organisations work

through key contacts (such as government-appointed professional officers) to

explain the technical changes that will make the law out of date – and, worse,

will prohibit the use of improved technology and techniques. Maintaining links

with professionals in other jurisdictions will allow examples to be provided to

law makers. The new Australian regulations provide an example of appropriate

documentation, as does the Botswana Land Policy.

4.9 Offer relevant training courses that

clearly explain, encourage and enable cooperative and action-based working by

organisations, within a clearly understood framework of the roles of each level/

sector

It is important that courses clearly explain the nature of the entire land

administration process, and the various organisations and sectors involved,

whilst often concentrating on certain aspects. For instance, land survey courses

need to explain the land registration system as well as the broader land

administration system. This embodies the T-shaped skills principle – that

effective practitioners need to have a breadth of understanding across a range

of activities, along with detailed understanding of their chosen area of

specialisation. This is as equally relevant to start-of-career training courses

as it is to lifelong learning courses.

Courses must also attempt to embed the concept of the need to work across

disciplines and organisations – which can then be developed further as students

from the courses go to work for different employers and in different sectors.

In a truly sustainable system, those developing training courses work very

closely with those in practice and responsible for policy development and

operational delivery, to ensure that the courses meet practitioners’ needs in a

timely way whilst being firmly rooted in academic knowledge and discipline.

|

Survey courses around the world need to produce students who have the

professional and technical capability to complete the work that is

required of them. The design of courses must ensure sufficient academic

rigour, but also that this is grounded in reality. Courses will

therefore need to adapt constantly, recognising societal and cultural

norms and evolving market needs. A recent study of education for valuers

found mismatches between the professional education and skills of

surveyors as provided within academia, and the needs of the professional

practice in which the surveyors are employed on graduation. Some of the

reasons for this were found to be onerous generic educational

requirements imposed by universities, lack of resources, failures in

communication, and inadequate guidance by professional bodies as to the

requirements of professional practice. A partnership approach between

academia, practitioners and professional bodies is found to be able to

work effectively, with professional bodies accrediting academic courses

on the basis of threshold standards and, overall, on whether the courses

prepare students for the profession. By contrast, those courses

developed without a strong professional practitioner voice did not

produce students who were prepared to cope with the challenges of

professional practice.

Summarised from Kakulu and Plimmer, 2009 |

|

The Problem Based Learning (PBL) approach applied at Aalborg University,

Denmark is both project-organised and problem-based. In order to provide

for the use of project work as the basic educational methodology, the

curriculum is organised into general subjects or “themes” normally

covering a semester. The themes chosen in a programme are generalised in

such a way that the themes in total will constitute the general aim or

professional profile of the curriculum. The themes provide for studying

the core elements of the subjects included (through the lecture courses

given) as well as exploring (through the project work) the application

of the subjects in professional practice. Traditional taught courses

assisted by actual practice are replaced by project work assisted by

courses. The aim is broad understanding of interrelationships and the

ability to deal with new and unknown problems. In general, the focus of

university education becomes more on “learning to learn”. A

consequence of this shift from teaching to learning is that the task of

the teacher is altered from transferring knowledge into facilitating

learning. Project work also fulfils an important objective: the student

must be able to explain the results of their studies and investigations

to other students in the group. This skill is vital to professional and

theoretical cognition: knowledge is only established for real when one

is able to explain this knowledge to others. In traditional education,

the students restore knowledge presented by the teacher. When the

project organized model is used, the knowledge is established through

investigations and through discussion between student members of the

project group. The knowledge, insight, and experiences achieved will

always be remembered.

Summarised from Enemark, 2009 |

Key questions:

- Do education and training courses for surveyors reflect the reality of

professional practice?

- Are training courses regularly reviewed with key input from practising

professionals?

- Are staff from your organisation invited to participate in other

organisations’ training courses – and do staff from other organisations

participate in your organisation’s training courses – to assist in the

spread of information and in building relationships?

- Do training courses provide students with a clear overview of the entire

land administration system and the various organisations involved, before

providing detailed education in particular components of it?

- Do training courses include examples of successful collaborative working

between organisations and individuals?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, training courses are unlikely

to provide students and graduates who can succeed in professional practice. This

will significantly reduce the benefits of the education and place additional

pressures on the professional accreditation and membership tests of the various

professional bodies.

Many jurisdictions have good examples of successful collaboration between

academia and professional practice, including external examiners from

professional practice, and professional body accreditation of academic courses.

Professional bodies which maintain links with their peers in other countries

will be able to provide such examples, along with suggestions for initial

low-risk stages which will prove the benefit of this approach to those who are

sceptical.

4.10 Share experiences through structured

methods for learning from each others’ expertise and experiences, with this

learning fed back into organisational learning

Busy people do not spend sufficient time learning from experiences. This

problem increases with the increasing business and personal pressures on us all,

and the increasing expectation that instant communication requires instant

decision making.

It is, however, well documented that collating and using lessons learned from

particular tasks can shorten the time to complete future tasks. This process

need not be lengthy – but neither should the time given to it be unnecessarily

restricted.

In a truly sustainable system, proper time is given to a structured learning

process which involves all of the affected individuals and organisations. The

results are agreed and widely shared to facilitate wide and ongoing learning.

|

The most commonly used project management frameworks require that a

Lessons Learned report is completed as part of the completion of a

project. In the PRINCE 2 methodology, the Lessons Learned report is

generally completed in a workshop which brings together all involved

parties and considers what went well, what went less well, and what

lessons can be learned for future projects. Many organisations now bring

key lessons learned together into a manual for successful projects. The

same process can – and should – be easily applied to the development of

policy or completion of surveys. Information provided by a Task

Force member

|

|

The growing numbers of GeoPortals and other web-based tools allow a

place to share such learning across countries and continents – the

Knowledge Portal developed by the Global Spatial Data Infrastructure

Association (GSDI) is one such example (http://geodatacommons.umaine.edu/network/home.php).

The portal offers the opportunity for any organisation to deposit and

examine documents, find contacts in other organisations around the

world, and participate in a range of discussion forums. Information

provided by a Task Force member

|

Key questions:

- Do you complete a structured learning process with those involved at the

end of a project?

- Do you share the results of this learning with others who might benefit

from it now or in the future?

- Do you use web-based systems to share and gain learning?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, you are probably not giving

enough priority to learning lessons as a basis for ongoing improvement. The

tried and tested techniques around lessons learned, and the burgeoning web-based

portals, provide ample opportunity to learn and to share, and this is a crucial

element of developing sustainable, effective institutions and organisations.

Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), 2008, Making Land

Work: Volume 1 – Reconciling Customary Land and Development in the Pacific.

Available from

http://www.ausaid.gov.au/publications/pdf/MLW_VolumeOne_Bookmarked.pdf

Duindam, A., Bloksma, R., Genee, H. and van der Veenm J., 2009, State of Play

of the Operational and Legally Bound Spatial Planning SDI in the Netherlands.

Proceedings of GSDI 11, Rotterdam, June 2009. Available from

http://www.gsdi.org/gsdiconf/gsdi11/papers/pdf/129.pdf

Enemark, S., 2004, Building Land Information Policies. Proceedings of UN/FIG

Special Forum on Building Land Information Policies in the Americas,

Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26-27 October 2004. Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

Enemark, S., 2009, Surveying Education: Facing the Challenges of the Future.

Proceedings of the FIG Commission 2 workshop, Vienna, 26-28 February 2009.

Available from

http://www.fig.net/commission2/vienna_2009_proc/papers/opening_enemark.pdf

FIG, 1999, The Bathurst Declaration on Land Administration for Sustainable

Development. FIG Publication No 21. Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

FIG, 2002a, The Nairobi Statement on Spatial Information for Sustainable

Development. FIG Publication No 30. Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

FIG, 2002b, Business Matters for Professionals, FIG Publication No 29.

Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

FIG, 2005, Aguascalientes Statement – The Inter-Regional Special Forum on

Development of Land Information Policies in the Americas. FIG Publication No 34.

Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

FIG, 2008, Capacity Assessment in Land Administration. FIG Publication No 41.

Available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

Greenway, I., 2009, Building Institutional and Organisational Capacity for

Land Administration: an update on the work of the FIG Task Force. Proceedings of

the FIG Working Week, Eilat, May 2009. Available from

http://www.fig.net/srl/

HMT, 2000, Public Services Productivity: Meeting the Challenge. Available

from

http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/241.pdf

Kakulu, I. I. and Plimmer, F., 2009, Real Estate Education versus Real Estate

Practice in Emerging Economies – a challenge for globalization. Paper presented

to ERES conference, Stockholm, Sweden, June 2009. Available from

http://eres.scix.net/cgi-bin/works/show?eres2009_394

Land Equity International Ltd, 2008, Governance in Land Management – A Draft

Conceptual Framework. Available from

http://www.landequity.com.au/publications/Land%20Governance%20-%20text%20for%20conceptual%20framework%20260508.pdf

Mathuba, B. M., 2003, Botswana Land Policy. Presented at an International

Workshop on Land Policies in Southern Africa, Berlin, 26-27 May 2003. Available

from

http://www.fes.de/in_afrika/studien/Land_Reform_Botswana_Botselo_Mathuba.pdf

OXERA (Oxford Economic Research Associates Ltd), 1999, The economic

contribution of Ordnance Survey GB. Report available at

http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/oswebsite/aboutus/reports/oxera/index.html

UNDP, 1997, Capacity Development – Management Development and Governance

Division Technical Advisory Paper 2. Available from

http://mirror.undp.org/magnet/Docs/cap/Capdeven.pdf

UNDP, 1998, Capacity Assessment and Development. Technical Advisory Paper No.

3. Available from

http://mirror.undp.org/magnet/Docs/cap/CAPTECH3.htm

UN FAO, 2007, Good Governance in Land Tenure and Administration. FAO Land

Tenure Studies Number 9. Available from

http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a1179e/a1179e00.htm

Published in English

Copenhagen, Denmark

ISBN 978-87-90907-77-8

Published by

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Kalvebod Brygge 31–33, DK-1780 Copenhagen V

DENMARK

Tel. +45 38 86 10 81

Fax +45 38 86 02 52

E-mail: FIG@FIG.net

www.fig.net

January 2010

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS