FIG PUBLICATION NO. 45

Land Governance in Support of

The Millennium Development Goals

A New Agenda for Land Professionals

FIG / World Bank Conference

Washington DC, USA 9–10 March 2009

Stig Enemark

Robin McLaren

Paul van der Molen

Contents

1. Foreword

2. Executive Summary

Global Challenges

Land Governance Supporting the Global Agenda

The Conference

Conclusions

3. Declaration

4. Conference Profile

Setting the Scene

5. Land Governance

Supporting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

Responding to the New Challenges

6. Conference Highlights and the Way Forward

Theme 1: Land Governance for the 21st Century

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 2: Building Sustainable and Well Governed Land

Administration Systems

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 3: Securing Social Tenure for the Poorest

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 4: Making Land Markets Work for All

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 5: Improving Access to Land and Shelter

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 6: Land Governance for Rapid Urbanisation

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

7. Appendices

Conference Programme

Reference to Proceedings

Orders for printed copies

1. Foreword

This publication is a result of the joint FIG-World Bank

Conference on “Land Governance in Support of the Millennium Development

Goals: Responding to New Challenges” held at the World Bank Headquarters

in Washington DC, 9–10 March 2009. It includes a report identifying the

highlights of the conference, the ways forward, and also a declaration

produced as a conclusion of the conference.

The organisers wish to thank all who participated, contributed,

supported and encouraged this conference. The support and funding providing by

the ESRI, Trimble, The Dutch Kadastre, GTZ, Leica, and ITC are gratefully

acknowledged. Finally, we wish to convey our sincere gratitude and thanks to all

the delegates who travelled from all parts of the world to attend this

conference and participated so actively and enthusiastically.

This report will be tabled at the FIG Congress in Sydney 11–16

April 2010 and at the World Bank Land Conference in Washington 26–27 April 2010.

This should assist national governments and land professionals to develop and

improve appropriate land governance in support of the Millennium Development

Goals and to address the new challenges.

Stig Enemark

FIG President |

Klaus Deininger

Lead Economist, World Bank |

World Bank Headquarters, Washington D.C., USA

2. Executive Summary

The 21st century has dawned with the world facing global issues of climate

change, critical food and fuels shortages, environmental degradation and natural

disaster related challenges as today’s world population of 6.8 billion continues

to grow to an estimated 9 billion by 2040 when over 60% will be urbanised. This

is placing excessive pressure on the world’s natural resources.

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) form a blueprint agreed to by

all the world’s countries and the world’s leading development institutions to

support the mitigation of these global issues. The first seven goals are

mutually reinforcing and are directed at reducing poverty in all its forms. The

last goal – global partnership for development – is about the means to achieve

the first seven. These goals are now placed at the heart of the global agenda.

Land Governance Supporting the Global Agenda

Land governance is about the policies, processes and institutions by which

land, property and natural resources are managed. This includes decisions on

access to land, land rights, land use, and land development. Land governance is

basically about determining and implementing sustainable land policies and

establishing a strong relationship between people and land. Sound land

governance is fundamental in achieving sustainable development and poverty

reduction and therefore a key component in supporting the global agenda, set by

adoption of the MDGs. The contribution of the global community of Land

Professionals is vital.

Measures for adaptation to climate change will need to be integrated into

strategies for poverty reduction to ensure sustainable development. The land

management perspective and the role of the operational component of land

administration systems therefore need high-level political support and

recognition.

The conference involved 200 invited international experts and was jointly

organised by FIG and the World Bank with the overall objective to emphasise the

important role of Land Governance in implementing the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs) and responding to new global challenges. The responses are

categorised into the following six conference themes:

The Land Governance for the 21st Century theme focused on adapting and

improving our approaches to land governance to be more sensitive to and

supportive of these new challenges and to make stakeholders fully aware of the

incentives to adopt this paradigm shift. Good land governance must not only

control and manage the effective use of physical space, but must also be

holistic to ensure sound economic and social outcomes. The World Bank’s land

governance assessment framework provides countries with an opportunity to assess

and improve their current approaches to meet these global challenges, especially

climate change. Land governance must be further democratised by developing tools

for all stakeholders to increasingly participate and form partnerships in policy

formulation, implementation and monitoring all within more realistic timeframes.

The international community must also provide guidance and contract evaluation

tools and services to mitigate the risks for countries negotiating international

land acquisition contracts – the so called ‘farmlands grab.’

The Building Sustainable, Well Governed Land Administration Systems (LAS)

theme emphasised the role of LAS in providing the infrastructure for

implementing land policies and land management strategies in support of

sustainable development. LAS must evolve and must be aligned with the current

needs of a country through the requirements defined in a land policy framework.

LAS are most effective when managed as a business and have a sustainable funding

model based on a robust business case. Early investments in positioning

infrastructures can realise significant benefits in a wide range of land

applications. However, it is estimated that LAS are only fully operational and

work reasonably well in about 30 and mainly western countries. Thus, the

fundamental support of LAS in achieving the MDGs is of serious concern.

The Securing Social Tenure for the Poorest theme addressed the need of

securing tenure for the rural poor and the 1 billion slum dwellers world-wide;

reaching 1.4 billion by 2020 if no remedial action is taken. Conventional

cadastral and land registration systems cannot supply security of tenure to the

vast majority of the low income groups. It is imperative that we develop

innovative new approaches that can be scaled to solve this escalating global

issue. It is essential to establish good land policies that achieve equitable

land distribution and fair laws that are pro-poor. However, new pro-poor,

scalable tools to achieve security of tenure for the slum dwellers need to

include social and customary tenure approaches and the corresponding LAS should

adopt the Social Tenure Domain Model that is currently being developed in a

cooperation between FIG, ITC, UN-HABITAT and the World Bank.

The Making Land Markets Work for All theme identified ways of breaking

down the barriers to land markets access. In many countries certain land rights

are not a tradable commodity, such as customary land rights, allodial lands,

religious lands etc., and access to the market may be restricted by financial,

corruption, social or informational reasons. The sub-prime mortgage crisis and

the unbundling of property rights into complex commodities have also exposed

high risk groups and in many cases poor people have been left landless. Fairer

and more equitable access to the land sales and rental markets can be achieved

through an effective primary land market, the provision of homeowners guarantee

funds, government co-ordination of social housing, market transparency to reduce

corruption and the introduction of monitoring tools to evaluate the performance

of the functioning of land markets, e.g. the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports.

The Improving Access to Land and Shelter theme focussed on

interventions to support the increasing number of citizens who do not have

access to land and adequate shelter. This exclusion is caused, in many cases, by

structural social inequalities, inheritance constraints, conflicts, and often

land administrations systems are ineffective and expensive for the end user.

Land reform is unfinished business and interventions are still necessary to

reduce the structural inequalities since market forces will not naturally

alleviate the situation. The forced migration of people in conflict situations,

or the result of disasters, causes significant access issues to land and

shelter. Longer term measures for housing and land and property rights need to

be put in place to support social stability. Finally, more effective gender

responsive land tools are required to widen women’s access to land. All these

interventions need to be applied within the broader context of economic growth

and poverty reduction policies.

The Land governance for Rapid Urbanisation theme reviewed responses to

this global phenomenon that will result in 60% of the world’s population being

urbanised by 2030. This incredibly rapid growth causes severe ecological,

economical and social problems, with over 70% of the growth in developing

countries currently happens outside of the formal planning process. However,

urbanisation with the continuing concentration of economic activities in cities

is inevitable and generally desirable. Increasing economic density remains the

objective for all areas at different stages of urbanisation. Due to the

significant dynamics of urbanisation, urban planning and public infrastructure

provision tends to be reactive rather than a guide to development. It is

therefore essential that appropriate priorities for policies are set at

different stages in urbanisation, essentially providing the elements of an

urbanisation strategy that conforms to the reality of growth and development.

Effective and democratised land governance is at the heart of delivering the

global vision of our future laid out in the MDGs. However, the route to this

vision is rapidly changing as a series of new environmental, economic and social

challenges pervade and impact every aspect of our lives. Land Professionals have

a vital role to play and we must understand and respond quickly to this on-going

change. Our approaches and solutions across all facets of land governance and

associated Land Administration Systems must be continually reviewed and adapted

so that we can better manage and mitigate the negative consequences of change.

Central to this is our response to climate change and food security.

Washington D. C., USA.

3. Declaration

FIG–World Bank Declaration on Land Governance in Support

of the Millennium Development Goals

All countries have to deal with governing their land. They have to

deal with the governance of land tenure, land value, land use and land

development in some way or another. A country’s capacity may be advanced

and combine all the activities in one conceptual framework supported by

sophisticated ICT models or, more likely, capacity will be involved in

very fragmented and basically analogue approaches.

Effective systems for recording various kind of land tenure,

assessing land values and controlling the use of land are the foundation

of efficient land markets and sustainable and productive management of

land resources. Such systems should be based on an overall land policy

framework and supported by comprehensive land information and

positioning infrastructures.

Sustainable land governance should:

- Provide transparent and easy access to land for all and

thereby reduce poverty;

- Secure investments in land and property development and

thereby facilitate economic growth;

- Avoid land grabbing and the attached social and economic

consequences;

- Safeguard the environment, cultural heritage and the use

natural resources;

- Guarantee good, transparent, affordable and gender

responsive governance of land for the benefit of all including the

most vulnerable groups;

- Apply a land policy that is integrated into social and

economic development policy frameworks;

- Address the challenges of climate change and related

consequences of natural disasters, food shortage, etc.; and

- Recognise the trend of rapid urbanisation as a major

challenge to sustain future living and livelihoods.

As an outcome of the conference, some key recommendations have

emerged. These are argued in more details in this report in terms of the

way forward within the six themes of the conference. |

4. Conference Profile

The conference was jointly organised by FIG and the World Bank with the

overall objective to emphasise the important role of Land Governance in

implementing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and responding to new

challenges such as Climate Change and Urban Growth. The conference

demonstrated how FIG and the World Bank are working in parallel to achieve

these global aims.

The conference aimed to illustrate the far reaching impact of land

institutions, highlighting successes, failures and remaining challenges for

improving land, and identify resources and measures that can be drawn upon

by interested parties.

The conference was recognised as a major milestone in tackling global

land issues and was attended by around 200 invited internationals experts

within the land sector representing governments, UN agencies, development

agencies, professionals, academia and the private sector.

The conference was divided into six themes:

- Land Governance for the 21st century;

- Building sustainable, well governed land administration systems;

- Securing social tenure for the poorest;

- Making land markets work for all;

- Improving access to land and shelter; and

- Land governance for rapid urbanisation.

About 80 papers were presented in 20 sessions. Proceedings are available

on both the FIG and the World Bank websites and the full programme of the

conference is presented in Appendix 1.

- The President of Liberia, live in a video-conference with

the opening session, described the rebuilding of Land

Administration institutions to provide access to land as

essential to rekindle economic growth and social stability

following the 25 years of war that tore her country apart. Her

one request to the conference was to be “quick in solving her

land issues”.

- India has embarked on converting their deeds based land

registration system for rural areas into a title based one. This

is a daunting task involving over 140 million owners and 430

million records in nine scripts and 18 languages. However, it is

estimated that it will result in an uplift of 1.3% GDP and

reduce petty corruption in the land sector by around US$700

million/year (more than India’s entire science and technology

budget). [R. Sinha]

- A similar process is unfolding in Indonesia where it is

estimated that 7.3 million hectares of land currently lies idle

or abandoned with a significant direct opportunity loss each

year. The process is being accelerated by using mobile land

offices in rural areas – including motorcycles. [J. Winoto]

|

5. Land Governance

Arguably sound land governance is a key to achieve sustainable

development and to support the global agenda as set by adoption of the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Land governance is about the policies,

processes and institutions by which land, property and natural resources are

managed. This includes decisions on access to land, land rights, land use,

and land development. Land governance is basically about determining and

implementing sustainable land policies.

Sound land management requires operational processes to implement land

policies in comprehensive and sustainable ways. Many countries, however,

tend to separate land tenure rights from land use opportunities, undermining

their capacity to link planning and land use controls with land values and

the operation of the land market. These problems are often compounded by

poor administrative and management procedures that fail to deliver required

services. Investment in new technology will only go a small way towards

solving a much deeper problem: the failure to treat land and its resources

as a coherent whole. Such a global perspective for land governance and

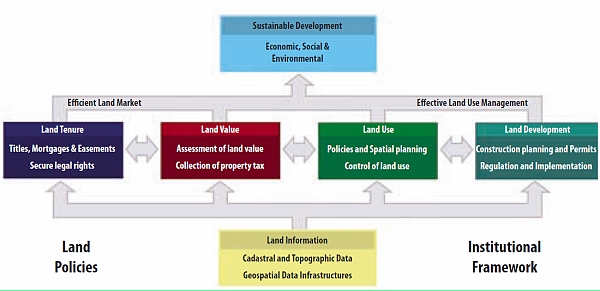

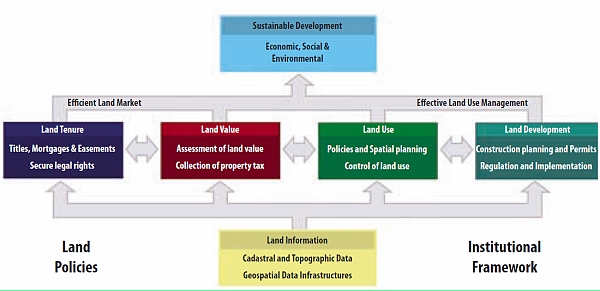

management is shown below (Enemark).

A Global Land Management Perspective.

Land governance and management covers all activities associated with the

management of land and natural resources that are required to fulfil

political and social objectives and achieve sustainable development. This

relates specifically to the legal and institutional framework for the land

sector. The operational component of the land management concept is the

range of land administration functions that include the areas of: land

tenure (securing and transferring rights in land and natural resources);

land value (valuation and taxation of land and properties); land use

(planning and control of the use of land and natural resources); and land

development (implementing utilities, infrastructure, construction planning,

and schemes for renewal and change of existing land use). All of these are

essential to ensure control and management of physical space and the

economic and social outcomes emerging from it.

Land Administration Systems (LAS) are the basis for conceptualising

rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Property rights are normally

concerned with ownership and tenure whereas restrictions usually control use

and activities on land. Responsibilities relate more to a social, ethical

commitment or attitude to environmental sustainability and good husbandry.

In more generic terms, land administration is about managing the relations

between people, policies and places in support of sustainability and the

global agenda set by the MDGs.

Good governance is generally recognised as critical for sustainable

growth and poverty reduction. At the same time, the impact of the legal and

institutional frameworks that determine how land related issues are managed

has only recently been fully appreciated.

Supporting the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs)

The eight MDGs form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries

and the world’s leading development institutions. The first seven goals are

mutually reinforcing and are directed at reducing poverty in all its forms.

The last goal – global partnership for development – is about the means of

achieving the first seven.

These goals, as shown in figure below, are now placed at the heart of the

global agenda. To track the progress in achieving the MDGs a framework of

targets and indicators has been developed. This framework includes 18

targets and 48 indicators enabling the ongoing monitoring of the progress

that is reported on annually.

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education

Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

Goal 4: Reduce child mortality

Goal 5: Improve maternal health

Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

Goal 8: Develop a Global Partnership for Development |

The Eight Millennium Development Goals.

The MDGs represent a wider concept or a vision for the future, where

proper land governance is central and vital and where the contribution of

the global community of land professionals is fundamental. This relates to

the areas of providing the relevant geographic information in terms of

mapping and databases of the built and natural environment, and also

providing secure tenure systems, systems for land valuation, land use

management and land development. These aspects are all key components in

achieving the MDGs.

Responding to the New Challenges

The key challenges of the new millennium are clearly listed already. They

relate to climate change; food shortage; urban growth; environmental

degradation; and natural disasters. These issues all relate to governance

and management of land.

The challenges of food shortage, environmental degradation and natural

disasters are to a large extent caused by the overarching challenge of

climate change, while the rapid urbanisation is a general trend that in

itself has a significant impact on climate change. Measures for adaptation

to climate change must be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction

to ensure sustainable development and for meeting the MDGs.

The UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon has stated that “climate change is

the defining challenge of our time”. He said that ”combining the impacts of

climate change with the current global financial crisis we risk that all the

efforts that have been made by countries to meet the Millennium Development

Goals and to alleviate poverty, hunger and ill health will be rolled back.

It is clear that those who suffer the most from the increasing signs of

climate change are the poor. Those that contributed the least to this

planetary problem continue to be disproportionately at risk.”

On the other hand the global challenge of climate change also provides a

range of opportunities. The Executive Director of UN-Habitat Dr. Anna

Tibaijuka has said (Urban World, March 2009) that “prevention of climate

change can be greatly enhanced through better land–use planning and building

codes so that cities keep their ecological footprint to the minimum and make

sure that their residents, especially the poorest, are protected as best as

possible against disaster”. This also relates to the fact that some 40

percent of the world´s population lives less than 100 km from the coast

mostly in big towns and cities. A further 100 million people live less than

one metre above mean sea level.

The Director General of UN-FAO, Jacques Diouf, has said (World Summit of

Food Security, November 2009) that “in support to climate change mitigation

and adaptation policy, the FAO created a National Forest Programme Facility

in 2002’”. The initiative is presently supporting 70 countries and regional

organisations. In 2008 FAO established the United Nations Collaborative

Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in

Developing Countries followed by a global forest monitoring system in

support of carbon accounting and payments.

Adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, by their very nature,

challenge governments and professionals in the fields of land use, land

management, land reform, land tenure and land administration to incorporate

climate change issues into their land policies, land policy instruments and

facilitating land tools. More generally, sustainable land administration

systems should serve as a basis for climate change adaptation and

mitigation. The management of natural disasters resulting from climate

change can also be enhanced through the creation and maintenance of

appropriate land administration systems. Climate change increases the risks

of climate-related disasters, which cause the loss of lives and livelihoods,

and weaken the resilience of vulnerable ecosystems and societies.

In short, the linkage between climate change adaptation and sustainable

development should be self evident. Measures for adaptation to climate

change will need to be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction to

ensure sustainable development. The land management perspective and the role

of the operational component of land administration systems therefore need

high-level political support and recognition.

6. Conference Highlights and the Way

Forward

Theme 1: Land Governance for the

21st Century

At the start of the 21st century the world is facing critical global food

and fuels shortages, climate change, urban growth, environmental degradation

and natural disaster related challenges as today’s world population of 6.8

billion continues to grow to an estimated 9 billion by 2040. This is placing

inordinate pressure on the world’s natural resources.

The surge in the price of key food products such as rice and wheat, which

last year hit record highs, sparked food riots in many countries. Food

security has become a key global challenge. In response to the crisis, many

countries and private corporations are exploring new ways of safeguarding

their supplies of natural resources; especially crops for food and

bio-fuels. A global search is now underway to identify ‘underutilised’ land

in areas suitable for agricultural production and to acquire the land for

large scale agricultural production. Significant areas of land in Africa,

India and South America have now been bought or leased to foreign countries

or corporations – the so called ‘farmlands grab.’

Although these investments attract capital along with technology and

market knowledge to potentially improve agriculture, there are many inherent

concerns that are not always covered in the associated contracts:

agricultural produce is directly exported from countries with a food

deficit; there is no ‘unused’ land and in many cases local people are taken

off the land with little compensation; the easiest land to acquire is

government land and the benefits normally go to the political elite rather

than the local people; large scale agriculture does not employ significant

numbers of local people; and much common land, such as grazing land, is

targeted and lost. It is increasingly relevant that we strengthen land

governance across the globe to ensure that all stakeholders understand their

roles and responsibilities in managing land, property and natural resources

within a sustainable and equitable framework.

The key challenges of the new millennium are all interconnected, with

many being perpetrated by climate change. Our understanding of the problems

and the formulation of potential solutions will only be achieved through a

holistic approach involving collaboration across the professions. Land

professionals have a key role in this alliance through the effective

management of spatial information related to the built and natural

environments and the application of good land governance to help mitigate

the damaging impacts on our world and society. We need to adapt our

approaches to be more sensitive to and supportive of these new challenges

and make stakeholders fully aware of the incentives for adopting this

paradigm shift. Good land governance must not only control and manage the

effective use of physical space, but must also ensure sound economic and

social outcomes.

Highlights of the Conference

- The World Bank has sponsored a project to develop and test a general

framework for assessing land governance. This is based on the Public

Expenditure and Financial Accountability methodology and involves five

themes, 24 indicators and 80 dimensions and is currently being tested in

pilot projects in Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Peru and Tanzania. This

assessment framework should be adopted by countries to assess and

improve their current approaches to Land Governance.

[T. Burns]. This work is complemented by the recently launched UN-FAO

initiative to produce Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of

Tenure of Land an activity being sponsored by RICS and FIG [M.

Torhonen].

- Many countries are strengthening their land governance arrangements

and reports were provided by Tanzania [L. Kironde], Peru [V. Endo] and

Kyrgiz Republic [A. Endeland] where they highlighted an urgent need to

improve governance in the land sector to ensure economic sustainability,

poverty alleviation and peace and security. Advances have been made in

land policies, recognition of a continuum of rights, communal rights,

the rights for women, stakeholder involvement in developing land

policies and laws, improved planning solutions and land based taxation.

However, most countries still have problems in the institutional

arrangements and capacity to deliver effective land governance.

- Large scale, international land acquisitions are increasing,

especially in Africa, driven by food security and the scramble for

biofuels [D. Byerlee]. There are issues around the export of

agricultural produce directly from countries with a food deficit, the

fact that there is no ‘unused land’ and significant loss of ‘commons’ to

local people.

- A proposal was made to engage communities as key stakeholders in

climate change and poverty mitigation by extending the bundle of rights

associated with land to include key natural resources and the rights to

carbon [G. Barnes].

- The Land Reporting Initiative, organised by the International Land

Coalition monitors land issues and trends and seeks to facilitate

collaboration between civil society and inter-governmental organisations

to promote better monitoring of land issues for ensuring impact on

poverty reduction [A. Mauro].

New Zealand.

1. Adapt land governance to be more supportive of our global challenges

Effective and democratised land governance is at the heart of delivering

the global vision of our future laid out in the MDGs. However, the route to

this vision is changing as a series of new environmental, economic and

social challenges spread through and impacts every aspect of our lives. The

degree of change and uncertainty in our world is increasing. As land

professionals we must understand and respond quickly to this on-going

change. Our approaches and solutions across all facets of land governance

must be reviewed and adapted so that we can better manage and mitigate the

negative consequences of change. Central to this is our response to climate

change.

2. Adopt the world bank assessment framework to improve current

approaches to land governance

Poor land governance has far-reaching economic and social consequences:

lack of inward investment and economic growth; limited poverty reduction;

increased deep-rooted conflicts; significant corruption and land grabbing.

This all leads to social instability. The increase in population and the

growing demand for land driven by food security and biofuels needs will

increase the value of land. These trends will worsen the current land

related problems unless land governance can be improved to cope with these

new challenges. The World Bank’s land governance assessment framework

provides countries with an opportunity to assess and improve their current

approaches to land governance. This should be an on-going process and

countries should transparently publish their assessment results in the

public domain. The assessment framework should also be regularly updated to

ensure that the land governance we aspire to is increasingly relevant to the

new millennium, global challenges, especially climate change.

3. Increase participatory tools to build partnerships and further

democratise land governance

As the visibility and role of land governance strengthens in the wider

policy arena, it is essential that we further democratise land governance by

developing tools for all stakeholders to increasingly participate and form

partnerships in policy formulation, implementation and monitoring. For

example, land policy reforms contribute more fully to poverty reduction and

sustainable development when closely related to processes that empower civil

society, especially poor men and women, in decision-making processes. And

more effective aid is provided when development partners are involved early

in planning policy implementation. These tools need to be shared across the

international community. However, secure land rights are fundamental in

minimising arbitrary dispossession and maximising local benefit.

4. Provide contract evaluation tools to safeguard nations from

inappropriate large scale, international land acquisitions

The ethical basis and the economic and social impacts of the increasing

number of large scale, international land acquisitions, driven by food

security and the scramble for biofuels, need to be questioned. Large areas

of relatively unproductive land across the globe are being leased or sold to

foreign governments and corporations for large scale agricultural

production. This mostly involves government land and commons. The contracts

rarely provide benefits to local people and there are major concerns about

the environmental and social impacts, especially when agricultural produce

is being exported from countries with food deficits. Too often these

contracts are signed without sufficient due diligence on their affect on the

ground. The international community needs to provide contract evaluation

tools and services to countries negotiating international land acquisition

contracts.

5. Adopt realistic timeframes to ensure more effective land policy

implementations

Over the past decade around 15 African nations have successfully

formulated their National Land Policies through participative and inclusive

approaches. However, their corresponding record in implementing their

National Land Policies is less successful. This lack of success derives, in

many cases, from overly ambitious implementation timescales and insufficient

institutional and legal reforms to support the new land policies. Countries

need to adopt a more realistic and incremental approach to implementation,

where small successful steps will build optimism and effectively change the

power relationships over land issues in the country.

Ghana.

Theme 2: Building Sustainable and Well

Governed Land Administration Systems

Land Administration Systems (LAS) provide the infrastructure for

implementing land policies and land management strategies in support of

sustainable development. This infrastructure includes the institutional

arrangements, a legal framework, processes, standards, land information,

management and dissemination systems, and technologies required to support

allocation, land markets, valuation, control of uses, and development of

interests in land. LAS are dynamic and evolve to reflect the people-to-land

relationships, to adopt new technologies and to manage a wider and richer

set of land information.

The LAS is the fundamental infrastructure that underpins and integrates

the land tenure, land value, land use and land development functions of land

administration to support an efficient land market that fully demonstrates

sustainable development. The land information should form part of a wider

spatial data infrastructure (SDI) to ensure its wider use in a range of

social, economic and environmental applications and services. However, it is

estimated that LAS are only fully operational and work reasonably well in

about 30 and mainly western countries. Thus, the fundamental support of LAS

in achieving the MDGs is of serious concern.

To support an inclusive approach, a ‘well governed’ LAS is an

infrastructure that is managed in such a way that the products and services

are of the appropriate quality level, affordable, easy to use, support short

transaction times and are fully transparent. The delivery of this outcome

requires a combination of business and technical skills. The sustainability

of LAS is enhanced when supporting legal frameworks define a view of the

role and function of LAS in the implementation of the land policy;

especially for land related laws, such as land law, registration law, fiscal

law, land use law etc.

The LAS must operate within and respond to the requirements within a land

policy framework. Recent World Bank research reports indicate ‘land tenure’,

‘land markets’ and ‘socially desirable land use’ are main drivers for a land

policy. These three goals comprise a whole range of instruments, such as the

forms of land tenure and how they are recognised in the country, the level

of land tenure security that should be provided, the interventions in the

land and credit market that are beneficial, the nature of land use planning,

state land management and land acquisition for the public good, use of land

taxation for budget generation and land use steering, valuable land reform

options and workable solutions for land conflicts. The land policy is not

isolated as it must be embedded in the wider political agenda of poverty

eradication, sustainable agriculture and housing, protection of the

vulnerable people, equity of social groups and women, rapid urbanisation,

food security, climate change and slum upgrading etc.

It is crucial to understand that LAS can never be an end in themselves;

their nature is to serve society, whatever that society currently looks

like. For many countries this is definitely a break with the past, because

elements of LAS, such as land registration and cadastral boundary surveying,

are considered historically as an instrument of the colonial or otherwise

ruling powers to securing their own land rights. ‘Sustainable’ land

administration systems are therefore systems that serve society well, by

providing effective sets of products and services that are fully inclusive

to meeting demand now and in the future. This includes the poor who are

currently excluded from participating in many countries.

- Success in the case of land administration systems is based to a

large extent, on the availability, access and applicability of related

spatial information. In this context, the concepts, technologies and

resources associated to the development of sound spatial data

infrastructures (SDI) at multilevel have the capacity to optimise land

administration processes and land management [S. Borrero].

- Positioning Infrastructures, such as Continuously Operating

Reference Systems or Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) support

a range of functions in society: from the traditional function of

supporting surveying and mapping processes to enabling the monitoring of

global process such as those associated with climate change and

extending to real time precise positioning services employed in

industries [M. Higgins].

- A key component of a land administration system is to put in place

organisations that are sufficiently robust to develop, enable and ensure

the effective operation of surveying and land administration activities.

Building the necessary institutional and organisational capacity for

land administration is crucial to achieve sustainable development and

meeting the MDGs [I. Greenway].

- Since the early 1990s the World Bank has lent around $1 billion to

37 projects (not counting the contributions by the countries) across

many countries in the World Bank Europe and central Asia region (ECA) to

implement land administration systems and to support land markets. The

resulting land markets now contribute between 15%–25% of GDP in these

countries. This initial phase of investment in land governance is now

maturing and the World Bank have conducted a review of the lessons

learned [G. Adlington].

- Decentralisation of land administration and management is essential

in order to achieve efficient, cost effective and equitable services for

all participants. Institutional frameworks should be created at the

local level to resolve all local-level land administration

inefficiencies [E. Silayo].

- The economic value-add created by spatial data infrastructures (SDI)

is significant for the overall economy, together with the value of the

SDI itself, and it also stimulates efficiency savings in various

sectors. SDIs benefit public administration by eliminating

inefficiencies by introducing e-government practices [G. Adlington].

1. Create a land policy framework to let the LAS function more

effectively

LAS products and services must be aligned with the current needs of a

country. These requirements must be defined in land policy, describing how

governments intend to deal with the allocation of land and land related

benefits and how LAS are supposed to facilitate the implementation. Such

implementation includes the rules for land tenure and land tenure security,

the functioning of the land market, land use planning d development, land

taxation, management of natural resources, land reform etc.

2. Adopt a business led approach to deliver better managed LAS

Although based on scientific concepts, methods, and principles, land

administration is a business process that should be managed as a business.

Therefore, land administrators need to be acquainted with business

administration knowledge, safeguarding good process design and workflow

management, performance monitoring and daily financial management. Managers

need to have knowledge of both professional matters and ICT matters, to

guarantee good alignment between business objectives and ICT support. A

sharp eye for customer relations is a prerequisite for sound performance,

and a sufficient justifier for investments. Essentially, land administration

functions need to be transparent and free from corruption.

3. Invest early in positioning infrastructures to realise benefits in a

wide range of land applications

Historically, national triangulations have formed the base for

consistency in land surveying. Nowadays, these positioning infrastructures

constitute not only the base for land surveying and place based land

information in all its forms, but the infrastructures also supports a wide

range of land applications. The performance of LAS has proven to be enhanced

strongly by applying appropriate ICT-tools, including satellite imagery,

aerial photographs and GNSS. Early investments in this positioning

infrastructure are crucial.

4. Promote evidence of LAS to support economic growth and poverty

reduction

LAS can be sustainable when the solution fulfils its expected function by

users on a continuous and satisfying basis. Good quality management

procedures continually safeguard the relevance of the LAS in current and

changing times. Maintenance of the records and underlying information, as a

minimum, is of paramount importance and financial arrangements should allow

for registers and maps to reflect the situation on the ground day by day.

Without appropriate funding arrangements this is difficult. Therefore the

development of the LAS must be based on a realistic business model. Although

investments in land administration are usually justified through qualitative

arguments, more attention should be paid to providing robust quantitative

evidence such as contributions to economic growth and poverty reduction that

are of direct interest to politicians.

Chile.

Theme 3: Securing Social Tenure for

the Poorest

Today there are many rural poor and around 1 billion slum dwellers

world-wide. UN-Habitat estimates that if the current trends continue, the

slum population will reach 1.4 billion by 2020, if no remedial action is

taken. These astonishing figures are fuelled by the rush to the cities and

over half of the world’s population today live in urban areas. Current

trends predict the number of urban dwellers will keep rising, reaching

almost 5 billion in 2030 where 80% will live in developing countries.

In this perspective, where one of every three city residents lives in

inadequate housing with few or no basic services, it becomes urgent to focus

on informal settlement and to support the MDG 7, target 11 to have improved

the lives of least 100 million slum dwellers by 2020.

Most of the urban poor do not have secure tenure within these large

informal settlements. Securing formal recognised rights to land and housing

in urban areas will generally give people access to basic services and it

may also help them to access legal and financial services to raise capital

to invest. It is therefore essential that we put in place good land policies

that focus on achieving equitable land distribution and fair laws that take

into account the interests of the poor.

Conventional cadastral and land registration systems cannot supply

security of tenure to the vast majority of the low income groups. It is

imperative that we develop innovative new approaches that can be scaled to

solve this escalating global issue. Land Administration Systems will have to

be modified to accommodate a wider range of levels of tenure security and

integrate customary systems of tenure. New low cost surveying tools are

emerging and need to be integrated into cadastral surveying processes. The

understanding that enjoying secure land tenure is also a matter of human

rights and social justice, encourages unconventional solutions, whether it

regards forms of land rights, levels of security or land administration

tools. The Land Professional has a key role to play in delivering these more

appropriate tools.

Many communities across the world have land rights under communal or

customary systems that are often not secure in law. Land and resource rights

include both strong individual and family rights to residential and arable

land and access to a range of common property resources such as grazing,

forest and water. There is group oversight and rules to keep land within the

group that are normally derived from customary norms and principles. The

lack of legal security can lead to vulnerability in practice, e.g. when

predatory states re-allocate land to foreign investors.

The policy challenge is to decide what kinds of rights, held by which

categories of claimants, should be secured under tenure reform and

integrated into a Land Administration System. This is complex since

customary tenure regimes are not static and traditionbound, but dynamic and

evolving and the associated boundaries are often ambiguous, or flexible or

overlapping. The diversity, imprecision and flexibility makes it difficult

to codify them and provide them with legal definition. However, this is

essential to provide this section of society with a potential route out of

poverty and reduced threats of eviction.

Highlights of the Conference

- Land tenure reform remains a key policy issue in Africa, given the

large proportion of the population that relies on land and natural

resources for their livelihoods. It is not enough to recognise the

socially and politically embedded character of land rights, or the

unequal outcomes of contemporary forms of ‘enclosure’. Privatisation and

complete individualisation of land are uneven and contested, and in many

places the nature and content of land rights remain quite distinct from

‘Western-legal’ forms of property [B. Cousins].

- The land-sea interface is one of the most complex areas of

management. It is the gateway to ocean resources, a livelihood for local

communities, a reserve for special flora and fauna and an attractive

area for leisure and tourism. Strong arguments were made that land use

management in coastal areas should recognise social justice and embrace

pro-poor policies and adopt environmentally balanced approaches to

development. [D. Dumashie].

- The Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) is a multi-partner initiative

to support pro-poor land administration solutions. The initiative is

based on open source software development principles. The STDM, as it

stands, has the capacity to broaden the scope of land administration by

providing a land information management framework that would integrate

formal, informal, and customary land systems and integrating

administrative and spatial components [C. Lemmen].

- A low cost solution for providing geo-referenced village (cadastral)

maps seem to have a big potential for security of tenure and land use

planning in India [K. Murthy].

- Modern technology and digital mobile devices can be used as key

means for providing land tenure security while at the same time

improving the level of equity, fairness and stability in land tenure

systems [M. Barry].

- Evidence from a large scale land administration project in Ethiopia

suggest that implementation of a decentralised, transparent and cost

effective process of land registration is possible, but also that

failure to do so may in many situations miss out significant economic

and possible social benefits [T. Alemu].

1. Adopt a continuum of rights approach to deliver faster and wider

security of tenure to the poor

UN-HABITAT’s ‘continuum of rights’ recognises that rights to land and

resources can have many different forms and levels. Just as ‘land tenure’

has the notion of a statutory land right, other forms of land rights, such

as anti-eviction ‘right’, group tenure etc., refer to the recognition of

somebody’s land possession within the social community and can be called

‘social tenure’. Land professionals must include ‘social tenure’ in their

scope of professional attention and deliver more social tenure oriented

solutions.

2. Include customary tenure in Land Administration Systems to reduce

vulnerability

The diversity, imprecision and flexibility of communal or customary

systems makes it difficult to provide them with legal definition. However,

it is essential that these social groups are provided with appropriate forms

of tenure security within Land Administration Systems that do not restrict

their ongoing evolution. These sections of society, especially in rural

areas, need a potential route out of poverty and reduced threats from

farmland grabs, for example.

3. Adopt the Social Tenure Domain Model to support pro-poor Land

Administration System solutions

Traditionally, the technology supporting Land Administration Systems uses

models and terminology that is aligned with formal, legal systems, making it

impossible to adequately support social tenure systems with pro-poor

technical and legal tools. However, the development of a solution to this

problem is being supported by FIG called the Social Tenure Domain Model

(STDM), originally developed as the Core Cadastral Domain Model (CCDM). The

STDM is a tool to deal with the kind of social tenure that exist in informal

settlements (and also in areas based on customary tenure) that cannot be

accommodated in traditional Land Administration Systems. It is planned to

provide this ISO standards based solution as free and open source software

and should be available as a tool for local communities as well as public

authorities.

4. Develop pro-poor and gender sensitive land tools to improve the lives

of the poor

UN-Habitat has an agenda around the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) that

aims to facilitate the attainment of the MDGs through improved land

management and tenure tools for poverty alleviation and the improvement of

the livelihoods for the poor. All Land Professionals are encouraged to

support and contribute to this effective initiative to alleviate the current

level and scale of poverty.

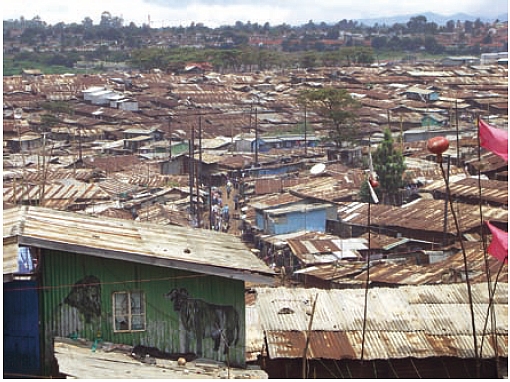

Nairobi, Kenya.

Theme 4: Making Land Markets Work for

All

The land market, more precisely the market in property rights to land, is

not always characterised as a perfect market, where demand and supply are

brought to the most efficient use by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market

mechanism. In many countries certain land rights are not a tradable

commodity, such as customary land rights, allodial lands, religious lands

etc. Even when land rights are fully tradable, the market can still be far

from perfect since access to that sales market may be restricted by

financial, corruption, social or informational reasons.

Many people cannot afford an initial investment in land and there is

growing interest in the functioning of the land rental market. Agricultural

leases and residential rents are easier to pay through regular income

generation, while buying needs a lot of savings or credit facilities. There

are also many social obstacles to land market participation as people might

not be familiar with how the market functions through illiteracy and missing

education, for example. Lack of transparency and information and complex

regulations also creates obstacles. The resulting restrictions mostly

disadvantage of the poor, while being at the advantage of the powerful

elites. This then results in unequal land possession, and at worse, land

grabbing and speculation.

Markets in land rights seldom exist in customary areas, where ownership

of land is vested in the community. Allocation of use rights is de facto and

executed by chiefs, family heads or even the President of the nation.

Scarcity of lands, growing population, and mobility of people lead in many

cases to a demand for individual land rights in these commonly owned lands.

In addition, land claims are increasingly coming from governments or from

project developers and examples show that chiefs of representatives of

collectives do not always understand that they act on behalf of the

community and not for themselves. This erosion of customary areas is

creating the ‘new tragedy of the commons’ symbolising the land grab in these

areas.

Participating in the market requires a certain purchase power. This might

come from savings, but it might take a long time before people are able to

buy property. Land and houses are particularly suitable for serving as

collateral for a loan. However, as the subprime mortgage crisis in the US

revealed, inappropriate loans being provided to high risk groups can lead to

foreclosures and distress sales, leaving poor people landless. The financial

services sector and governments have a major responsibility to set up

regulatory frameworks to reduce the risk of re-occurrence.

Land markets need to be accessible by all and supported by land

information systems that provides transparency in information about

ownership rights and associated transactions and an institutional framework

that delivers simple, affordable and efficient land administration services.

In many countries the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports’ facilitate the

streamlining of procedures to make transactions simpler, quicker and

cheaper.

However, the concept of property is rapidly evolving from simple

ownership or use, towards complex commodities generated by unbundling

property rights, into separate tradable mineral rights or carbon credits,

for example. This ‘unbundling’ of rights leads to speculative collateralised

debt obligations and, as the recent financial crises has highlighted,

stronger regulation is required across the land and financial services

sectors.

- Formal land markets accelerate wealth generation whilst informal

land markets fail to generate sufficient national wealth to relieve

poverty. Governments therefore need to build land administration systems

to manage the full range of land related commodities [J. Wallace].

- Land and agriculture will increasingly become strategic issues in

the next decade, requiring considerable allocations of attention,

resources and capital. Institutions, such as the World Bank and FAO have

a significant role to play in facilitating partnerships amongst

governments, rural communities and the private sector agri-business

chain. [A. Selby].

- The World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports’ have inspired countries,

such as Burkina Faso, to simplify the number of procedures involved in

land market transactions, opening up the land market to a wider section

of society [ A. Traore].

- Land markets mature and operate to generate significant wealth for

the economy. Land markets migrate through the following five steps as

they mature: land as a societal resource; land rights in terms of secure

tenures; land trading enabling land transfer; land market enabling

dynamic land trading and securitisation; and a complex commodities

market. A key driver in this evolution is the building of mature

cognitive capacity in the public where all stakeholders understand the

land market that is transparent and supports inventiveness and trade in

ideas. [J. Wallace].

- There are two principal types of market imperfections in relation to

the land and property markets: firstly, informational inefficiency where

market participants are not fully informed about market circumstances;

and secondly, allocative inefficiency where a person’s actions have an

impact for others that go beyond legitimate competition. Therefore,

access to common property resources need to be regulated and property

rights provided for one have to be provided for all [R. Grover].

- Low-cost land certification has a significant and positive effect on

the amount of activity in the land rental market. Such reforms generate

reduced transaction costs in the land market. This encourages poor

female households to rent out their land and it becomes easier for

people to access land for renting in [S. Holden].

- Government land acquisition in emerging economies such as China must

be applied through fair and responsible rules and respect the existing

land tenures, especially of the poorest [S. Jin].

The Way Forward

1. Improve primary land delivery to boost land markets

In many countries the trade in land rights between parties (secondary

land market) can only develop after the delivery of land to citizens by the

government (primary land market). When the primary market does not function

well, the secondary market cannot effectively develop causing informal or

illegal land occupation, slums and illegal land markets. This land delivery

is hampered by long lasting procedures, complex regulations, and weak

government structures, for example. Therefore, an effective primary land

market is a prerequisite for any market improvement.

2. Don’t leave social housing to market forces

A consequence of a poorly functioning primary land market is the lack of

social housing supply. When the land market does not work for certain groups

in society, especially the poor, the principles of institutional economics

dictate that governments should assume responsibility for providing social

housing. The allocation of houses in this situation should not be left to

the land market, but to social housing organisations. Governments should

meet their responsibility to

coordinate social housing.

3. Guarantee homeowners funds to protect the poor

When secured credit is used for production purposes, such as buying

livestock, seeds and fertilizers, opportunities for capitalising on property

might exist, on the understanding that the loans can be reasonably paid

back. Some countries offer state guarantees in the form of homeowners

guarantee funds, which aim at protecting the poor against unbearable debts

when, unfortunately, loans cannot be paid back and the property might be

forcedly sold against liquidity value. The development of such homeowners

guarantee funds is highly advisable.

4. Reduce corruption through transparency of markets and incorruptible

land professionals

Corruption investigations have revealed that the land sector is prone to

significant grand and petty corruption. Transparency is the key to fair and

equitable access to the land sales and rental market for all. A high

standard of ethics in the work of land administrators is also a prerequisite

to combat bribing and land grabbing. Therefore, the FIG developed codes of

conduct should be adopted by national and local land professional

associations.

5. Offer fair compensation when the State acquires land and evicts

people

Often the poor suffer from unfair acquisition of land by the State.

Although the justification for land taking might be legitimate, private

right holders should be treated fairly when losing their land rights. In

many circumstances, local government officials play an important role in

offering fair compensation for people to be evicted and land professionals

should develop transparent procedures for land acquisition with fair

compensation mechanisms.

6. Introduce monitoring tools to measure the effective functioning of

the land markets

Many countries are simplifying the number of procedures and reducing the

time and costs involved in transactions in the land market and are realising

economic benefits. Monitoring tools need to be introduced to evaluate the

performance of the functioning of the land market. An example of an existing

tool is the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports’. Land administration systems

also need to support both traditional and modern communal systems to ensure

that they are protected within the market context.

Mozambique.

Mexico.

Theme 5: Improving Access to Land and

Shelter

An increasing number of citizens do not have either permanent or

temporary access to land and adequate shelter. This exclusion is caused, in

many cases, by structural social inequalities, inheritance constraints,

conflicts, non pro-poor and pro-gender land policies and land

administrations systems that are ineffective and expensive for the end user.

Without a range of appropriate interventions being applied within the

broader context of economic growth and poverty reduction policies, social

exclusion and poverty will continue to spiral out of control; already 90% of

all new settlements in sub-Sahara Africa are slums.

Land markets, or formalisation of existing land rights, in spite of their

great flexibility and usefulness to the poor, are not a magical solution for

addressing structural inequalities in countries with highly unequal land

ownership which reduces productivity of land use and restricts development.

To overcome the legacy of such inequality, ways of redistributing assets

such as land reform are still needed. While the post war experiences of

Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, China showed that land reform can improve equity

and economic performance, there are many other cases where land reform could

not be fully implemented or even had negative consequences that illustrate

the difficulties involved. If, within a broader strategy of poverty

reduction, redistributive land reform is found to be more cost-effective in

overcoming structural inequalities than alternatives then it needs to be

aligned with local needs and complemented by access to political support,

managerial ability, technology, credit and markets for the new owners to

become competitive.

Every year a significant number of people are forced to migrate from

their homes due to conflict situations, evictions or natural disasters. In

Iraq, it is estimated that over 5 million Iraqis are currently displaced by

violence and the rebels continue to benefit through the lack of a solution.

In many countries there are no national policies and associated guidelines

that comply with international human rights standards for the eviction of

residents of slums and informal settlements. There are examples of evictions

involving over 50,000 persons in Africa and these slum residents live in

constant fear of eviction. Natural disasters also cause significant

displacement of people; the 2004 tsunami displaced over 1.7 million people.

Effective and early solutions need to be identified and implemented to solve

the housing, land and property issues resulting from these events to enable

social and economic stability.

Only 2% of registered land rights in the developing world are currently

held by women. Many women have very restricted access rights to land and

shelter due to religious, cultural and legal constraints. This situation has

been exacerbated by the AIDS epidemic and requires the design of more gender

responsive land tools.

Highlights of the Conference

- Most violent conflicts are not “caused” by conflicts over land per

se, but almost every major eruption of violent conflict has had a land

dimension. It is essential to look anew at how institutional

arrangements and patterns of political organisation determine when land

becomes an object of violent conflict. If this is not done then

programmes that may be intended to promote participation or good

governance may in fact contribute to aggravating conflict in fragile

states [J. Putzel].

- Several papers reviewed progress of land reform programmes,

especially their impact on poverty, in West Bengal, South Africa and in

the Philippines where the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program has been

operational for 20 years [A. Balisacan & F. Bresciani].

- Michael Lipton [lunchtime talk] highlighted the impact on the land

tenure and land reform debate of three great, current adjustments: the

large global GDP setback; rising food and farm energy prices; and the

increasing uncertainty of water availability due in part to climate

change. These adjustments will strengthen the arguments and pressures

for redistributive land reform.

- One of the fundamental ways to strengthen women’s entitlements and

to make their claims over natural and physical assets more enforceable

is through legal reform [R. Meinzen-Dick]. However, legal reforms must

be accompanied by legal-literacy campaigns to ensure that both men and

women are aware of such changes.

The Way Forward

1. Continue effective and sustainable land reform to reduce poverty and

inequality

Land is poor people’s main and usually only productive asset. Around 1.5

billion people today have gained farmland due to land reform, resulting in

many being less poor, or not poor. However, huge land inequalities remain,

or have re-emerged, in many low-income countries; this has been caused by

inheritance rather than efficiency and generated inefficient, low-employment

farm output. In many developing areas with no, minor, ineffective or

incomplete land reform, the poorer half of farming people normally control

below 10% of farmland. The impact on the poor is compounded since not only

does extreme land concentration increase income inequality, but in

developing countries it also reduces farm output and slows growth.

2. Accept that land reform is an on-going process

Land reform interventions are still necessary, in many cases, to reduce

the structural inequalities since market forces will not naturally alleviate

the situation. Land reform is ‘unfinished business’. The new land reform

approaches adopted need to be carefully attuned to their target contexts to

attain their goals of reducing poverty and inequality, ensuring output

efficiency and growth, and achieving sustainability, stability and

legitimacy. Future approaches should be shaped and sensitive to a range of

constraints, including the degree of social and land rights inequalities,

demographic demand, genders rights and roles, resilience of customary

rights, willingness of land owners to cost share, economic affordability of

compensation and the capacity of the population to tolerate and support the

proposed changes.

3. Address land and shelter access issues up front in conflict and

disaster situations

The forced migration of people in conflict situations, or the result of

disasters, causes significant short and long term access issues to land and

shelter. Even where land is at the centre of the conflict, the emergency, or

first phase, is dominated by emergency issues and short-term’ism. It is only

in the second, or reconstruction phase, that housing, land and property

rights are treated within a medium to long term framework. Too often there

is little funding for the second phase by comparison to the first phase.

This means that housing, land and property issues in post conflict

situations are not always addressed adequately. The approach needs to be

improved and longer term measures put in place from the outset and the

delivery of solutions accelerated to support social stability.

4. Identify gender responsive land tools to widen women’s access to land

Women’s lack of access to and control over land is a key factor

contributing to poverty, especially in the increasing feminisation of

agriculture, and needs to be addressed for sustainable poverty reduction.

Although the policy statements of almost all donors active in the land and

natural resources sector emphasise women’s access to land and many countries

also make reference to gender equality in their constitutions, laws relating

to property rights do not often give equal status to women. Women’s access

to and control over resources is shaped by complex systems of common and

civil law as well as customary and religious laws and practices. The

practise and perception of a woman’s position in the household, family and

community still affects to what extent women can exercise their rights. The

challenge now is to translate this political will into action and produce

gender equality across the land sector. We need to identify practical

solutions, particularly at the grassroots level, that support women’s

effective and sustainable access to land and make policy-makers aware of how

this can be achieved.

Malawi.

Theme 6: Land Governance for Rapid

Urbanisation

Urbanisation is a major change that is taking place globally. The urban

global tipping point was reached in 2007 when over half of the world’s

population was living in urban areas; around 3.3 billion people. Although

this depends on the definition of ‘urbanisation’, as outlined in the World

Bank’s ‘World Development Report 2009, Reshaping Economic Geography’ (World

Bank, 2009). It is estimated that a further 500 million people will be

urbanised in the next five years and projections indicate that the

percentage of the world’s population urbanised by 2030 will be 60%.

This rush to the cities, caused in part by the attraction of

opportunities for wealth generation, has generated the phenomenon of

’megacities’ that have a population of over 10 million. There are currently

19 megacities and there are expected to be around 27 by 2020. Over half this

growth will be in Asia; the world’s economic geography is now shifting to

Asia.

Megacities exert significant economic, social and political dominance

over their hinterlands. Mega-urban regions are growing, especially in China

(Pearl River Delta) and the US (central east coast) to create clusters of

cities or “system of cities” and while not megacities in the traditional

form of centre and suburbs, they will form “multi-centre megacities”.

This incredibly rapid growth of megacities causes severe ecological,

economical and social problems. It is increasingly difficult to manage this

growth in a sustainable way. It is recognised that over 70% of the growth

currently happens outside of the formal planning process and that 30% of

urban populations in developing countries living in slums or informal

settlements, i.e. where vacant state-owned or private land is occupied

illegally and used for illegal slum housing. In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of

all new urban settlements are taking the form of slums. These are especially

vulnerable to climate change impacts as they are usually built on hazardous

sites in high-risk locations. Even in developed countries unplanned or

informal urban development is a major issue.

Urbanisation is also having a very significant impact on climate change.

The 20 largest cities consume 80% of the world’s energy use and urban areas

generate 80% of greenhouse gas emissions world-wide. Cities are where

climate change measures will either succeed or fail.

Rapid urbanisation is setting the greatest test for Land Professionals in

the application of land governance to support and achieve the MDGs. The

challenge is to deal with the social, economic and environment consequences

of this development through more effective and comprehensive spatial and

urban planning, resolving issues such as the resulting climate change,

insecurity, energy scarcity, environmental pollution, infrastructure chaos

and extreme poverty.

- The significant rapid urbanisation trend is recognised in the WB’s

‘World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography’ that sets

priorities for policies at different stages in urbanisation, essentially

providing the elements of an urbanisation strategy that conforms to the

reality of growth and development. [M. Friere].

- Unplanned urban growth causes significant ecological, economic and

social problems and risks, such as the threat of disasters. The

characteristics of these complex and dynamic systems are not well

understood to allow these risks to be managed and potentially mitigated.

There is a need for a multi-disciplinary perspective to better

understand the process of urbanisation and its governance and to develop

a set of urban indicators based on an integrated approach to physical,

social and environmental aspects of urban growth on one hand and urban

planning and land management on the other, to support good governance

and disaster risk reduction. [T. Kötter].

- Several papers identified unplanned or informal urban development in

developed countries as a major issue; this problem is significant in

more than 20 countries in the ECE region and affects the lives of over

50 million people [C. Potsiou]. In Albania, illegal developments

represent 40% of the built-up area of major cities [D. Dowall].

- The importance of good land governance has long been recognised by

the people of Kenya as a critical issue for sustainable socio-economic

development and an ambitious National Land Policy has recently been

formulated. [R. McLaren].

The Way Forward

1. Adapt land governance measures to support evolving cities for economic

growth

Urbanisation with the continuing concentration of economic activities in