| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 13B

Report

of the united nations inter-regional meeting of cadastral experts

Held al Lido Lakes Hotel, Bogor, Indonesia

18-22 March, 1996

This publication in .pdf-format

This publication in .pdf-format

|

The organisers of the conference wish

to acknowledge the support of the Land Administration Centre of New

South Wales, Australia, in the publication of this document. |

Contents

Background and Objective of the Meeting

Session 1: Welcoming Addresses

Session 2: Introductory Presentations 7

Sessions 3 and 4: Socio-Economic Justification

for Land Reforms and Cadastral Developments: An International Perspective

Session 5: Land Markets and Cadastral Processes

Session 6: Country Reports

Session 7: Country Reports (Continued)

Session 8: Country Reports (Continued)

Sessions 9 and 10: Working Group Discussions

on Improving the Efficiency and

Effectiveness of Cadastres and Land Markets

Session 11: Land Tenure Systems—Formal, Informal and

Customary Issues, Urban and Rural

Session 12: Role of the Private Sector in Cadastral

Activities

Sessions 13 and 14: Land Policy, Legal and

Institutional Issues

Sessions 15 and 16: Technical Cadastral

Issues

Conclusion

Appendix 1: Program and Agenda

Appendix 2: List of Delegates

Appendix 3: Opening Speech by Ir. Soni Harsono, State Minister of

Agrarian Affairs

Appendix 4: UN Meeting of Cadastral Experts

Terms of Reference

Appendix 5: Summary of the FIG Statement on the

Cadastre

Orders of the printed copies

Report of the united nations

inter-regional meeting of cadastral experts

Held al Lido Lakes Hotel, Bogor, Indonesia 18-22 March, 1996

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE OF THE MEETING

The UN Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Pacific held in Beijing in

1994 resolved as follows:

- The United Nations with the expert assistance of the International

Federation of Surveyors (FIG) and other relevant organisations support the

preparation of a regional and global compilation of optional components of a

cadastre, including legal aspects, land policy, institutional arrangements,

technology and economics.

- The preparation of case studies of cadastral systems and cadastral

reforms, such that countries of the region engaged in establishing or

reforming a cadastre may be aware of various options and learn from the

success and failures of others.

Due to the international importance of the subject, the meeting was included

in the Habitat II calendar of events entitled “the Learning Years”. This

activity was also part of the efforts to develop an active response to the

problems of land management and environmental protection as stipulated in the

Global Plan of Action for Habitat II, and to the recommendations contained in

Agenda 21.

As a result, an Inter-Regional Meeting of Experts on Cadastre was held in

Bogor, Indonesia from the 18 22 March, 1996. The United Nations worked closely

with the Indonesian agency Bakosurtanal and the International Federation of

Surveyors (FIG) in organising the meeting, and received an important

contribution from the Australian Agency for International Development.

The primary objective of the meeting was:

To develop a document setting out the desirable requirements and options for

cadastral systems of developing countries in the Asia and Pacific region and to

some extent globally.

The meeting recognised that all countries have individual needs and

requirements, but that countries at similar stages of development have some

similarities in their requirements. As such the meeting primarily examined the

requirements of three groups of countries, namely newly industrialised countries

such as Indonesia, countries at an early stage of transition such as Vietnam and

the South Pacific countries.

The meeting adopted the definition and description of a cadastre as set out

in the FIG Statement on the Cadastre. Reference was also made to the two

previous UN meetings of cadastral experts (1972 and 1985) and the Land

Administration Guidelines prepared by the United Nations Economic Commission for

Europe in 1996.

The meeting recognised that the key to a successful cadastral system is one

where the three main cadastral processes of adjudication of land rights, land

transfer and mutation (subdivision and consolidation), are undertaken

efficiently, securely and at reasonable cost and speed, in support of an

efficient and effective land market. As such the meeting concentrated on these

three cadastral processes to help identify desirable or appropriate options for

cadastral systems. In considering the range of options, differences were

highlighted for the three major groups of countries identified.

The meeting also recognised that increasingly a successful cadastral system

is based on a strong and cooperative working relationship between the government

and private sectors. This involves the roles of professionals in private

practice, and the roles of professional societies and associations. All

discussions attempted to highlight this relationship.

While the meeting focussed on the needs of the Asian and Pacific region, the

meeting also considered the requirements of three other groups of countries to a

lesser extent—namely the western developed countries, Eastern and Central

European countries moving to market economies, and the African states.

SESSION 1: WELCOMING ADDRESSES

As the Chief of the Indonesian Organising Committee, first of all let me

welcome you to this meeting. I highly appreciate your prompt response to the UN

invitation to attend this meeting, and the time you have made available from

your busy working hours as well as your effort to fly thousand of miles from

your home country to participate in this Inter-Regional Meeting of Experts on

Cadastre.

By this morning, delegates from fifteen of the seventeen countries scheduled

to participate in this meeting have already arrived, namely from Australia,

Cambodia, the People's Republic of China, Bulgaria, Malaysia, New Zealand,

Republic of Korea, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, Vietnam, The

Philippines, and Indonesia. The delegate from Canada sent her regrets that she

could not attend the meeting.

Before I continue with my report, I draw your attention to the sad news we

received last week that Mr. Pomaleu Salaiau, Surveyor-General of Papua New

Guinea, could not be with us today. He passed away on Friday, 8th March, 1996.

At this opportunity, allow me to recall the last facsimile I received from him,

dated February 13, 1996, I quote: “This is to confirm that the Surveyor-General

will be available for the Experts on Cadastre Meeting on 18 - 22 March, 1996.

Cheers! P. Salaiau, Surveyor General.” Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Pomaleu Salaiau

was well known to us, he was a very capable hard working man and a friend of

everyone. We will miss him very much. With your agreement, I ask you all to join

me in standing up and giving a moment of silence in remembrance of him and all

the work he has accomplished. Thank you.

This Inter-Regional Meeting on Cadastre organised jointly between United

Nations, Bakosurtanal and FIG was at first scheduled to proceed in December

1995, but then postponed to March 18-22, 1996. Thanks to the facsimile

technology, since January 1996 a speedy communication could be established with

the United Nations Department for Development Support and Management Services. I

have been in extensive contact with Mr. Valeri Moskalenko, Professor Ian

Williamson in Melbourne, Australia, Professor Peter Dale in United Kingdom, and

all cadastral experts who are participating in this meeting.

In parallel, we also have had several meetings with our National Land

Department which gave us full support to conduct this meeting, through the

setting up of an Indonesian delegation to fully participate in this meeting.

As you are aware, the funding of Experts and Observers to attend this meeting

was provided through the United Nations Regular Program of Technical Cooperation

for one expert per country, which covers travel, Daily Subsistence Allowance

(DSA) and insurance. The Government of Indonesia/BAKOSURTANAL has contributed in

the form of a subsidy to the DSA to meet the hotel accommodation and meals rate.

As for the entitlements of experts/observers financed by their employer

government, this is determined by the individual sponsors.

This Inter-Regional Meeting of Experts on Cadastre is scheduled to proceed

from today, Monday March 18, 1996 to Friday March 22nd 1996.

The first day, Monday March 18 will consist of four sessions from 0900 -

1700. The first session is set up for welcoming addresses, while in the second

session Professor Williamson will dwell on the detailed program and expected

outcomes, and Professor Peter Dale will review the previous UN meetings, the

Economic Commission for Europe Land Administration guidelines, and the FIG

statement on the cadastre. In sessions 3 and 4, experiences of each country will

be presented in relation to the plenary discussion on the socio-economic

justifications for cadastral reform. The second day, March 19, will be preceded

by the official opening by the State Minister of Agrarian Affairs and followed

by country presentations and discussion in four sessions.

On Wednesday March 20, one session is dedicated to parallel discussions in

three working groups and three plenary sessions. On Thursday 21 March, the first

session is given for working groups to discuss the administrative issues

followed by one plenary presentation by working group. The remaining sessions of

the day will be dedicated to working group discussion on technical cadastre

issues followed by a plenary presentation. In the evening, the drafting

committee will meet to prepare the final draft report and the final draft of the

Bogor Declaration. A dinner will be hosted by the Minister of Agrarian Affairs

followed by the official closing ceremony. On the last day, Friday 22 March,

three sessions are scheduled for the presentation and discussion of the draft

report and Bogor Declaration.

The Organising Committee fully understands that this Meeting is tightly

scheduled and will require a lot of energy and concentration from all of you. If

we can be of any assistance to make your stay a pleasant one, please do not

hesitate to let us know. Our staff will gladly assist you in your banking and

ticket arrangement as well as to render any other assistance you may require.

We truly hope that your stay will be a pleasant one and wish you a successful

meeting. I thank you for your kind attention.

Welcome Address by Dr. P. Suharto, Chairman of the

National Coordination Agency for Surveys and Mapping (Bakosurtanal)

First of all I am pleased to welcome you to this Inter-Regional meeting of

Experts on the Cadastre, held in the beautiful surroundings of Arya Duta Lido

Lakes Resort Hotel, at the foot of three mountains, Mt. Salak, Mt. Gede and Mt.

Pangrango. Thanks to all of you for responding to the invitation to participate

in this important meeting.

As Chairman of the National Coordination Agency for Surveys and Mapping, also

known as Bakosurtanal which is the Indonesian representative to the United

Nations Regional Cartographic Conference (UNRCC) for Asia and the Pacific, I

welcome the request from the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to host

this Inter-Regional Meeting of Experts on the Cadastre. As we all know, this

activity arose from a recommendation from the 13th UN Regional Cartographic

Conference for Asia and the Pacific in Beijing, People's Republic of China, in

1994, which is approved by the UN ECOSOC.

Indonesia is also a member of the International Federation of Surveyors

(FIG). In FIG, the Ikatan Surveyor Indonesia (the Indonesia Surveyors

Association) is representing Indonesia. In this meeting the President of the

Indonesia Surveyors Association serves as the Chief of the Organising Committee

as well as the member of the Indonesian delegation to this meeting.

Since the essence of this meeting is on cadastre, Bakosurtanal has received

the full support from the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and the National Land

Agency. The State Minister of Agrarian Affairs who is also the Head of the

National Land Agency has conveyed to me his willingness to formally open this

meeting. He apologises that he could not open this meeting today because he is

scheduled to attend a meeting with the People’s Representative Council, but he

will formally open the meeting tomorrow. This shows that the issues on cadastre

are considered a very important matter for Indonesia in entering the 21st

century.

In 1994, Indonesia started the Cadastre Reformation Program through the

National Land Agency: Land Administration Project (LAP), which encompasses the

components of the acceleration of Land Registration and Certification;

institutional arrangements; and policies to support long-term land management.

This program is felt necessary to respond to the pressing needs of extensive

population migration from rural to urban areas as well as the allocation of land

in accordance with environmentally sustainable development. The acceleration of

Land Registration and Certification is carried out systematically as well as

sporadically which is to be supported by the availability of geodetic control

networks and large scale maps. To expedite the completion of this national

program, our policy is to foster a close coordination between the sectoral

agencies involved, as well as to provide a greater role to private practice and

professional societies and associations as well as universities. The problem of

cadastre in Indonesia is a complex one.

During this meeting we intend to share our experiences in managing this

matter as well as learning from the experiences of other countries. I understand

that at the end of this meeting the ‘Bogor Declaration’ will be issued

consisting of summaries of major issues raised in this meeting as well as

identification of some key solutions. I personally hope that the Bogor

Declaration could serve as a pillar of our intention to play an active role in

contributing to the global need for responsible sustainable development on our

planet Earth.

Allow me in this opportunity to thank the UN ECOSOC and the FIG for

sponsoring this meeting, for the preparation of necessary materials, as well as

bringing all the distinguished experts from all parts of the world to this

venue. Furthermore, I would also like to extend my personal appreciation to the

support extended by His Excellency State Minister of Agrarian Affairs, Head of

the Lands Department, Mr. Soni Harsono and all his staff to make this meeting a

successful one. I would extend my thanks to the Department of Foreign Affairs

and the Indonesian Permanent Mission to the United Nations for their invaluable

assistance to make this meeting possible.

Last but not least, I thank the organising committee which on short notice

was able to set up all the arrangements for today’s meeting. My personal thanks

is also extended to the PCO and management of the Arya Duta Lido Lakes Resort

Hotel for rendering the professional management of this conference. I wish you

all a successful and fruitful meeting, and please come back again to Indonesia.

Thank you.

Opening Statement from Ms Beatrice Labonne, Director

of the Division for Environment Management and Social Development, Department

for Development Support and Management Services, United Nations, as delivered by

Mr Valeri Moskalenko

Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished experts and observers. I have the

privilege of welcoming you to the Inter-Regional Meeting of Experts on Cadastre,

on behalf of Ms. Beatrice Labonne, Director of the Division for Environment

Management and Social Development.

First of all I would like to thank the administration of the National

Coordination Agency for Surveying and Mapping of Indonesia, Bakosurtanal, which

kindly hosts this meeting, the International Federation of Surveyors, which

initiated this meeting and provides technical coordination, and the Australian

Agency for International Development, which contributed to the financing of the

meeting. The United Nations is pleased to organise this meeting with assistance

from NGOs like FIG, which according to Agenda 21 should be considered important

partners in the process of sustainable development.

Land is the most valuable asset of humanity. Nearly 150 million Km2 of the

Earth’s surface is dry land which provides all necessary elements for human

life. In addition it is estimated that by the year 2000 the world’s population

will exceed 6 billion, of which more than 50 percent will live in urban areas.

All 26 urban agglomerations projected to contain more than 10 million

inhabitants by the year 2010, are situated in developing countries. Indonesia

itself with nearly 2,050,000 Km2 of territory is a home for more than 180

million people, or nearly 88 per Km2 on average.

The growing demand for food, water, shelter, energy, recreational space and

other commodities creates a tremendous pressure on the environment and land;

conversely the degradation of land resource negatively impacts on the well being

of people. To address these issues the Member States of the United Nations

organised the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 on Environment and

Development, and the concept of economic growth and sustainable development has

become the guiding principle of the work of the United Nations. The City Summit

(HABITAT II) in June 1996 in Istanbul is the next international conference of

this kind. The purpose of the City Summit is to address two themes of global

importance: ‘Adequate Shelter for All’ and ‘Sustainable Human Settlements

Development in an Urbanising World’. The present meeting is part of efforts to

develop an active response to the problems of land management and environmental

protection as stipulated in Agenda 21 and the Plan of Action for HABITAT II, and

is included in the pre-HABITAT series of events referred to as the ‘Learning

Years’.

Effective land policy requires knowledge of what resources and productive

land exist, how it responds to development pressures, the value that land

resources represent to different sectors of society. The lack of knowledge of

these elements makes land management difficult if not impossible. Cadastre, or

the system of land registration, is one of the essential tools to assemble and

process data on land from different sources and to display them in a clear, map

and/or computer based graphical format.

The United Nations efforts to prepare this meeting indicate again the

importance which they attach to the land management problems. The Department for

Development Support and Management Services has a long history of assisting

governments in the development and use of cadastral systems. The mandate of the

department in cartography goes back to 1950s. The Department assists governments

in assessing the requirement of establishing or of strengthening land survey,

topographic, cartographic and map production establishments, cadastral and

Geographical Information Systems, and of Hydrographic Services. Subsequently it

assists governments in the formulation of relevant technical cooperation project

documents, and in applying results of operational research and latest

development of technology. The most recent example is a project in Bulgaria to

establish a GIS on polluted agricultural lands, including the collection,

processing and management of land information for the purpose of land resources

management and development, and environmental assessment.

A number of seminars and training courses were conducted in previous years

for developing countries, meetings of ad hoc group of experts on cadastre

surveying and land management systems were conducted and the results were

published in the proceedings of the United Nations Regional Cartographic

Conference and the World Cartographic Bulletin.

The most recent example of such a seminar is the International Seminar on

Geographic Information Systems (GIS), ‘City Sustainability and Environment’

which was held in Cairo in December 1995. The seminar was regarded as an

overwhelming success by the participants and an important landmark along the

road to Istanbul. The results of the Seminar were reported to the 3rd

Preparatory Committee for HABITAT II in February 1996.

Though with extremely limited resources and under pressure of the present

financial situation in which the United Nations now finds itself, DDSMS is still

able to respond to the most demanding questions of sustainable development.

The experts gathered in this hall have a great challenge before them which

will require tremendous efforts and extremely hard work to achieve in a short

time, the goal put before them. I hope that the results of the meeting will

contribute to the implementation of Agenda 21 and Habitat II Global Plan of

Action as well as to corresponding plans of the Member States. I look forward to

closely interacting with the Government of Indonesia to ensure that the results

achieved at this meeting are taken into consideration by the Member States in

Istanbul. I wish you every success in your deliberations and I hope that

collaboration with countries on this important topic will be fruitful and serve

sustainable development.

Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen. I bring you the greetings of the

FIG, the body that represents the international community of surveyors. It is a

matter to me of great pleasure and pride that we have been able to support this

important meeting. FIG is an international Non-Governmental Organisation

accredited by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC)

representing professional bodies of surveyors in nearly 70 countries. It was

founded in 1878 but for many years its activities took place more often than not

within Europe. It is only in relatively recent years that it has become truly

international—during my Presidency for instance we shall have our four major

annual meetings in Argentina, Singapore, England and South Africa.

The primary objective of the FIG is to ensure that surveying services meet

international needs. We seek to achieve this in part by collaborating with

international agencies in formulating and implementing policies for the use,

development and management of land and marine resources. The meeting this week

here in Bogor is an excellent example of what we seek to do, helping to

facilitate discussions that will I am sure lead to the identification of

possible solutions to problems. And whereas each country is unique with its own

social, political, economic, legal and physical environment there is much that

we can all learn from each other. One of the objectives of FIG is to create

fellowship and understanding so that through that we can learn from each other

alternative ways of tackling complex issues.

FIG also has a mission to support its member associations not only by

providing facilities for continuing professional development through the holding

of workshops, seminars and congresses and the dissemination of reports but also

through empowerment. By empowerment I mean the process of encouraging people to

recognise that they have skills and talents that are needed by society and

helping them to develop self-confidence. If we take Agenda 21 for example there

is much in that program that can of course only be undertaken by governments.

But there is much that even the humble surveyor can do to help, be he or she in

the public or the private sector. Agenda 21 is an opportunity for surveyors to

use their skills for the benefit of humankind.

The same applies in the cadastral field. Almost all systems around the world

are ripe for modernisation. Some are already trying to achieve this, some

already have but most are still struggling. New ideas and new approaches are

needed.

Cadastral systems and land registration are processes that underpin all

successful modern land resource management programs. This is obviously

recognised here in Indonesia from all that I know—indeed it is obviously

recognised by all delegates attending this meeting for otherwise they would not

have come. It is certainly something that is recognised by the FIG. At the risk

of embarrassing him, I would single out Ian Williamson as someone who has

contributed much not only to this meeting but to the development of cadastral

systems around the world. As Chairperson of our Commission 7 responsible for

cadastre and land management he has done more than anyone to promote cadastral

issues around the world and I would like to thank him on behalf of FIG for all

his support.

Now is not yet the time to thank our hosts here in Indonesia, other than to

say thank you for getting us off to such a good start. Nor is it yet time to

thank the UN—that will come at the end of our deliberations. All I would like to

say at this stage is that 'so far, so good'. We have all the makings of a great

meeting. From the FIG side I certainly am looking forward to the next few days.

I am also looking forward to identifying further areas where in the future we

possibly can help to make a contribution. I wish this meeting every success.

SESSION 2: INTRODUCTORY PRESENTATIONS

Overview of the Conference by Professor Ian

Williamson

At the beginning of this session, Professor Williamson outlined the

background to the conference and explained its objective. He then discussed the

importance of including subsequent sessions on topics such as socio-economic and

cadastral needs of different countries; justification of cadastral systems in

developing countries; land markets, limitations to efficiency and effectiveness,

and cadastral processes; traditional or customary land tenures; cadastral

systems and informal land tenure; the role of the private sector; cadastral

options; and the Bogor Declaration.

Land tenure has been described as the relationship between Man and Land and

although the gender implication of such a statement is open to question, what is

incontrovertible is that the formal and informal relationships between people

and the land that they use is of vital significance to every society.

Ironically, it is of such importance that many people take it for granted—like

the air that we breathe. It is only when systems begin to break down, just as

when the air gets too polluted, that people are forced to take action.

An awareness of modern problems in land registration dates back to just

before the outbreak of the Second World War when work began on a comparative

study into Land Registration by Sir Ernest Dowson and Mr. V.L.O. Shepperd. The

work was eventually published in 1952 and was the first modern comprehensive

documentation of cadastral issues. A year later, in 1953, the United Nations

Food and Agriculture Organisation (UN FAO) published a monograph on the

registration of rights in land. Written by the late Sir Bernard Binns, it has

recently been updated and reissued, reflecting a re-awakened interest in land

administration.

The concerns in the early 1950s came about in part because of the need to

ensure good agricultural production. When the UN FAO was formed just after the

Second World War, people in Europe were starving while Africa was a net exporter

of food. Today, the European Union is paying farmers not to grow food in what is

called the set-aside program. At the same time, in parts of Africa people are

now starving. In eastern Europe, agriculture did not keep pace with that in the

west and with the transition of centrally planned to market economies there has

been a revival of interest in land tenure. This transition has been accompanied

by major reviews of cadastral and land registration systems. Each country is

adopting a slightly different approach, reflecting its own history and culture.

In all but computerization, rather than looking forward, many countries have

been looking backward to their pre-nationalization systems.

A previous surge of interest in land registration took place in the late

1950s and early 1960s when countries formerly under British and French colonial

rule, gained independence. Diverse systems were established but unlike the

present developments in central and eastern Europe, retained features that were

determined by their colonial history. Countries in West Africa, formerly under

British colonial rule, for example, have many features in common with each other

but differ significantly from those countries that were administered by the

French, all of which have systems similar to that in France.

During the 1960s the British realised that it was time to take a fresh look

at cadastral surveying and land registration and in 1967 commissioned a study by

Mr. S. R. Simpson into land registration. This was intended to replace the work

of the late Dowson and Shepperd but its focus was very much on the legal aspects

of land registration. As a result a further study was commissioned in 1971

focusing on cadastral surveying within the Commonwealth, both works finally

being published in 1976.

The need for cadastral reform was not however confined to territories

formerly under colonial administration. In 1972 the United Nations called

together an ad-hoc group of experts in response to a resolution of the Sixth

United Nations Conference for Asia and the Far East that requested the UN to:

“... study in depth the problems of cadastral survey and to consider the

setting up of a permanent committee to keep developments in this field under

constant review.”

The Committee consisted of six members, one from Sweden, one from the United

Kingdom, two from the Netherlands, one from Germany and one from USA. There were

no representatives from Asia, although the resolution had come from that region.

The outcome was a succinct, simple and straightforward document that

distinguished between registration of deeds and registration of title, discussed

the legal, the fiscal and the multi-purpose cadastre and produced some

guidelines on how cadastral surveys could be made cost effective. The techniques

suggested included the use of photogrammetry in the initial establishment of a

cadastre. The recommendations remain as valid today as when they were written.

They have however largely been ignored. Simple photogrammetric techniques, for

example, are still rarely used although there is one major exception in the

Thailand Land Titling Project where the use of rectified photography has proved

to be cost effective.

At the Tenth United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the

Pacific a resolution was passed asking for a review and update on the 1972

Report. Eight experts—seven from Europe and one from Canada—met in 1983 in

Berlin and prepared a report on “Cadastral Surveying and Land Information

Systems”. This was published in 1985 in time for the Third UN Regional

Cartographic Conference for the Americas. The report endorsed the findings of

the “1972 Report”, stressing the need for speed, economy and efficiency—indeed

it incorporate the earlier document as an appendix for the benefit of those who

might not have seen it. The 1985 Report also laid emphasis on computer

technology, something that was not significant at the time of the 1972 study. It

stressed the need for management skills when operating a land information system

and addressed issues such as data protection and the need to introduce

safeguards against the physical destruction of data and the invasion of privacy.

The report drew heavily on the experiences of those operating the Swedish land

data system which was at the leading edge of computerised land information

systems at that time. The 1985 report includes the statement that:

“... bearing in mind the fact that while the population on the earth's

surface is increasing at an alarming rate, the size of the earth remains

constant and resources are becoming scarce, information on the land becomes

all the more important in the quest of social and economic development. The

collection, storage and orderly dissemination of land information are

important factors in the success of such development.”

The report marked a significant shift away from the idea that cadastral

systems are concerned with land ownership and possibly land taxation to promote

the concept that they are part of the basic infrastructure of society and are

concerned with land information and land management. Both the 1972 and the 1985

reports mirrored the thinking of the time but they did not alter the practice of

cadastre and land registration. In many countries the traditional approaches

were and remain too deeply entrenched for there to be great change without

political revolution. Nevertheless there are evolutionary processes that are

going on in most countries today, forced by new technologies and the greater

complexity of the societies within which we live.

This is reflected in the convening of this meeting here in Bogor where common

issues will be examined. It is also reflected in recent work by the United

Nations Economic Commission for Europe where as part of its contribution to the

forthcoming HABITAT II Conference, guidelines have been prepared for land

administration. These have been made with special reference to countries in

transition from centrally planned to market economies. The guidelines recognise

the importance of land markets and the need to manage information about land in

such a way as to secure optimum land resource management. The term 'land

administration' was chosen to cover land registration, cadastral systems and all

processes of managing the ownership, value and use of land.

The link between the ownership rights, land use rights and the market value

of land was recognised as important but the formal creation of such links is

institutionally difficult to achieve. In many countries there are records of

ownership held within the Ministry of Justice, records of value within the

Ministry of Finance and records of use either within the Department for the

Environment or else within the municipal administration and local authorities.

Yet the use of land determines its value, as does the security of its tenure.

Use rights and ownership rights determine what the citizens can do with their

land and property.

In many countries, when purchasing land, separate enquiries have to be made

to determine ownership and use rights. In England, for example, checking local

restrictions on the use of land can take anything from between ten days and a

month thus delaying the transfer of a property. In most countries there are

planning restrictions that affect what can be done with the land and hence its

value. In some countries, buildings are divorced from the land on which they

stand and are subject to separate administrative processes.

Against this complex background there is a move to link data sets in a

'one-stop-shop' approach so that a citizen need only make enquiry at one place

to find all the interests in any given piece of land or property. The almost

impossible task of getting different Ministries to surrender their

responsibilities and therefore their power over land matters can, from the

perspective of the land owner, be avoided by using wide area computer networks

linking each organisation. These linkages require the use of compatible

standards but leave the responsibility for keeping the data up to date with

those who generate the data in the first place. Thus the Land Registry can still

be responsible for the accuracy of land title data while the planning authority

can still be responsible for the restrictions on land use and the land owner can

obtain a single view of the combined data base.

Part of this approach is being driven by technology, part by a growing

awareness that cadastral systems should serve the people on the land rather than

the administrators in government offices. Of course many land registration

systems have focused on serving the needs of land owners, for instance by

guaranteeing the security of title and simplifying the processes of conveyancing

but many have ignored the needs of the community for good land management by

failing to provide relevant information. Similarly many cadastres have been

created 'top down' serving the needs of the cadastral surveyors and record

managers rather than the needs of land owners.

Common ground is now being sought with emphasis both upon the requirements

and responsibilities of the State and the needs of the individual. In this

process there has been much debate upon the role of the private sector. Should

the cadastre be under full governmental control with State surveyors and State

notaries carrying out all the necessary work or should at least some of the work

be done by the private sector? The answer will of course depend upon the

political situation in individual countries but it is worth stressing that

around the world an increasing amount of work that has traditionally been

regarded as a governmental responsibility is now being undertaken by the private

sector. There is also an increasing use being made of Non-Governmental

Organisations (NGOs).

The guidelines prepared by the UN ECE will formally be launched at the

HABITAT II Conference. They have however already had an impact. At a meeting at

the UN Headquarters in Geneva in February of this year representatives from 30

European countries came together to create a Meeting of Officials in Land

Administration (MOLA). In future the so-called 'Officials' will come from

governmental, cadastral or land registration organisations and will to some

extent mirror a pan-European group called CERCO (Comite Europeen des

Responsables de la Cartographie Officielle). CERCO is made up of the Heads of

national mapping agencies and is a forum for the exchange of information on

matters of mutual concern to European national mapping agencies—for instance

cross border mapping or issues such as copyright on surveying and mapping data.

MOLA hopes to play a similar role within Europe although it is acknowledged that

each cadastre or land registration system currently operates as if within an

island state and hence has little in common with its neighbours. Although it is

essentially a government sector initiative, it plans to involve a wide community

of experts including those in the private sector.

It is possible that this will change with the impact of the General Agreement

on Trade and Services (GATS) that is being administered by the World Trade

Organisation (WTO). GATS will require the creation of greater opportunities for

foreigners to work within a host nation's cadastral or land registration system.

The European Union is already seeking much greater freedom of opportunity for

its members to work anywhere throughout the Union. At present however MOLA is

bound together more by a common interest in solving problems for instance in

computerisation than in any move to share facilities or land and property data

between countries.

It is of course of interest that MOLA represents a European response to the

1972 request to the UN to set up 'a permanent committee to keep developments in

this field under constant review'. It is probable that MOLA will in due course

be anxious to market the expertise of its members on a global scale. At present

however its focus is strictly European. There is therefore still no global

'permanent committee' in the sense envisioned by the writers of the 1972 report.

As an ECOSOC accredited NGO, the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

is going someway towards filling what is still the gap, principally through its

Commission 7 which has been active in reviewing developments. FIG has for

instance produced a Statement on the Cadastre that complements the work that has

been done by the various United Nations agencies. It has also published two

reports on general land tenure issues, one being the results of a Round Table

meeting held in Melbourne, Australia with the UN FAO in 1994 and the other of

two meetings held in Harare, Zimbabwe in 1995, one with the UN FAO and the other

with the UN CHS (Habitat).

What emerged from these discussions was concern that land tenure arrangements

and cadastral systems in particular are not meeting the needs of the communities

that they were originally designed to serve. UN CHS has for example laid much

emphasis on the need to protect women's rights in land, the subject of a

conference held in Sweden in 1995 and a matter of focus in the New Delhi

Declaration in January 1996 that was issued at the end of the Global Conference

on Access to Land and Security of Tenure.

A striking feature of the New Delhi conference was the different perspectives

on land tenure held by the representatives of African and Asian nations.

Nevertheless the foundations on which they all stood were similar and it is only

at the higher levels that differences are apparent. The FIG Statement on the

Cadastre has attempted to get to that bottom level and as with the 1972 and 1985

reports and the work of the UN ECE it enunciates general principles that apply

to all.

The weakest part of all these studies is their understanding of land markets,

possibly due to the fact that the reports have been prepared by administrators,

lawyers or surveyors and not by economists. There is a general failure to

quantify the economic imperative of good land record management through which

comes good land management and a strong economy. In the west the relationship

between security of title and security for investments has been taken for

granted and is very difficult to assess in cost to benefit terms. All of the

documents cited above make supportive statements and arguments for a good land

titling system but none produces facts and figures to actually prove the case.

What can be shown is that countries with poor systems of land records have

relatively weaker economies than those with good systems. There is evidence that

efficient use of development project funds may be greatly impaired by poor land

information, especially in urban areas.

It is in the cities and towns that land markets tend to develop more rapidly

than in rural areas. There is of course great need for security of tenure in all

areas especially for farm land but relatively little buying and selling of rural

land takes place compared with urban. Much international aid has focused on

rural development, often with the objective of increasing food production. The

forthcoming HABITAT II Conference will focus the attention of the world on urban

environments and the fact that over the next thirty or so years two thirds of

the world's population will live in urban communities unlike today when two

thirds live in rural areas. The prime focus in most of the cadastral studies

referred to above has been on rural land which explains in part why there has

been limited discussion on land markets.

Today the cadastral debate often centres around the use of technology and the

development of multi-functional land information systems. The latter involves

more than the traditional players on the land titling stage - the lawyers, the

surveyors and the land administrators. The thread that runs through the reports

commented upon above includes such issues as the differences between the urban

and rural environments and the respective roles of the private and public

sector. What binds them all together is a search for the best way to respond to

the needs of land resource management by recording the ownership, value and use

of land in a way that is cost-effective and meets the needs of government and,

most importantly, of the local community. That search is not yet complete and

the challenge here in Bogor is to identify clearly the common problems, to look

at the many different solutions that have emerged over time, but ultimately to

choose the best way forward for each individual country, given its unique

circumstances.

Justification of Cadastral Systems in Developing

Countries, by Professor Ian Williamson

The paper by Williamson (1996) provides a justification for cadastral systems

in developing countries. The paper commences with a brief overview of cadastral

systems and argues that the debate about such systems should move from whether

cadastral systems are important or appropriate for developing countries, to what

constitutes an appropriate cadastre for such countries. Land titling, land

registration and land reform projects, or projects to regularise or formalise

land tenure arrangements, all require the support of or result in cadastral

systems. The promotion of the importance of cadastral systems in developing

countries draws heavily on the experiences of the World Bank, the Food and

Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Centre

for Human Settlements (Habitat) and several recognised international

authorities.

An effective cadastral system is important for the support of sustainable

economic development and environmental management within the context of Agenda

21 as agreed at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development

(UNCED) in Brazil in 1992. The trend for cadastral and land information systems

is to be increasingly justified on rigorous economic grounds, both in the

developed and developing worlds. Cadastral and Land Information Systems (LIS)

involve:

- definition of cadastre and land markets;

- key cadastral processes; and

- a continuum of land tenure arrangements

Cadastral systems are not ends in themselves. They have the potential to

support:

- effective land markets;

- increased agricultural productivity;

- sustainable economic development;

- environmental management;

- political stability; and

- social justice.

However, it is absolutely essential that each cadastral system is designed

appropriately to serve the needs of the respective country. Otherwise a

cadastral system can do more harm than good! There is a vast array of legal,

technical, administrative and institutional options available in designing and

establishing an appropriate cadastral system, again providing a continuum of

forms of cadastre ranging from the very simple to the very sophisticated.

The success of a cadastral system is not dependent on its legal or technical

sophistication, but whether land rights are adequately protected, with those

rights being able to be traded where appropriate (i.e. land rights can be

bought, sold, leased and mortgaged), efficiently, simply, quickly, securely and

at low cost. The developing world is dependent on the establishment of a system

of property rights and property formalisation in land, and associated

institutions, for economic development. Appropriate cadastral systems are

important, if not essential, for such systems to be established.

Statements both by the World Bank and United Nations confirm that the

formalisation of private property rights in land, which are an integral

component of an effective cadastral system, is very important for sustainable

economic development and environmental management in both urban and rural areas.

In rural areas a secure title is important:

- in promoting increased investment in agriculture;

- for more effective husbandry of the land;

- for improved sustainable development;

- to support an increase in GNP through an increase in agricultural

productivity;

- in providing significant social and political benefits leading to a more

stable society, especially where land is scarce.

In densely populated rural areas or areas of high value a cadastral system

also permits an effective land market to operate and allows an equitable land

taxation system to operate. In urban areas a cadastral system is essential to

support an active land market by permitting land to be bought, sold, mortgaged

and leased efficiently, effectively, quickly and at low cost. In addition a

parcel based land information system (not necessarily computerised), based on

the cadastre, is essential for the efficient management of cities. Cadastral

systems permit land taxes to be raised thereby supporting a wide range of urban

services, and allowing the efficient management and delivery of local government

services.

Where population densities cause land to be scarce, as farming becomes more

commercialised, when farming technologies improve and with the emergence of land

markets in both urban and rural sectors, the formal recognition of individual

and communal land rights, and the establishment of cadastral systems is very

important, if not essential, in developing countries to:

- promote security of tenure;

- improve access to land;

- promote economic and sustainable development;

- reduce poverty;

- support environmental management; and

- support national development in the broadest sense.

Thus, the question is not whether cadastral systems are essential, but what

constitutes from a technical, legal, institutional, administrative, economic and

social perspective, an appropriate cadastral system for a particular country or

jurisdiction at some point in time.

SESSIONS 3 & 4: SOCIO-ECONOMIC

JUSTIFICATION FOR LAND REFORMS AND CADASTRAL DEVELOPMENT: AN INTERNATIONAL

PERSPECTIVE

The meeting discussed the motivation for the interest of institutional

development of land administration in the participating countries. The question

was formulated as follows: What is the justification for cadastral reform in the

participating countries?

All delegates acknowledged there is great interest in institutional

development of the land administration system in the participating countries.

This interest is manifested in relatively large investment in improvements of

cadastral systems, including development of legislation, organisational methods,

and technology, in order to meet the demand from society. The demand comes from

the government, which has an interest in developing land administration systems

to promote economic development, social stability and economic growth. But the

demand is also high from the business sector, which wants clarity in security of

tenure, and predictable rules and legislation as a base for investment

decisions. Farmers and urban populations are also interested in secure titles to

land, clarity and transparency of land tenure for the same reason.

The table below shows the three most important reasons for cadastral reforms

as listed by the participating countries.

United Kingdom

- Computerisation.

- Need for simplification.

- Reduction of cost.

South Africa

- Justice and political stability.

- Reduced costs for land registration in areas with people who cannot afford

the current costs.

- Provision for group titles in areas with customary tenure and in other

areas in need of a low cost approach.

Vietnam

- Computerisation

- Social justice and equity.

- Support for the development of natural resources and protection of the

environment, and stopping degradation of soils and deforestation. Support for

land use planning.

Republic of Korea

- Improved protection of land rights.

- Better land management.

- Preventing land speculation.

Indonesia

- Security of tenure and protection of land rights.

- Reduction of land disputes.

- Efficient land market and to promote investment in land.

Thailand

- Secure titles to land to promote economic development.

- Create revenue for government.

- Provide information for land use planning.

- Standardisation of different systems to reduce costs and maintain

security.

Malaysia

- Indefeasible title and ownership guarantee by government.

- Lower costs for land transaction to promote an efficient and unambiguous

land market.

- Reduce litigation and boundary disputes.

People's Republic of China

- Promote economic growth and develop a land market.

- Promote better land use.

- Avoid boundary and land disputes.

Cambodia

- Computerisation to speed up the reform and to improve accuracy.

- Facilitate zoning and planning in order to fix land reservation and land

values.

- Improve rural land development bank and control credits.

Philippines

- Increase revenue from taxation of land for local governments.

- Accelerate settlement ownership to prevent land fraud.

- Support land use planning.

Bulgaria

- Security of ownership and transactions.

- Integration of registration and cadastral surveying and mapping, and

unification of rural and urban areas.

- Standardisation.

Russia

- Support political stability.

- Support economic growth.

- Create land market.

Australia

- Socio-economic applications of cadastral information.

- Environmental consciousness.

- Economic decision making.

Sweden

- Simplify cadastral organisation.

- Simplify procedures.

- Reduce cost through use of modern technology.

New Zealand

- Establish clear resource rights.

- Speed up property transfer and lower costs.

- Provide efficient support for traditional land tenure.

The participants at the conference represent a broad range of countries which

have reached different stages in their development and completion of the

cadastre. It was obvious that the main reason for countries which have not yet

implemented a formal cadastral system for the whole of their nation, to continue

and finalise the system, is to gain benefit from economic and social

development. For countries with established cadastral systems, the emphasis is

placed on matters to rationalise and increase the accessibility to their

systems, in order to reduce the costs for the government and the users, with the

help of modern information technology and through legal and organisational

reforms of procedures. In many Eastern European countries, there is a strong

political will to restore the cadastral systems and the parcels as they existed

before nationalisation.

In several countries, the aim of the cadastral reform is first of all to

promote economic development through the establishment of secure and protected

land rights, which can then serve as the basis for long-term investment

decisions in land development—both in rural and urban areas. Another reason for

cadastral development is to avoid land disputes and promote the development of a

land market and access to credit. Secure tenure will increase access to credit

with lower interest rates and increase real property values. These reasons were

particularly mentioned by delegates from the Republic of Korea, Indonesia,

Thailand, Malaysia, People's Republic of China, Bulgaria, New Zealand and

Australia. The need for development of methods of market valuation and training

of appraisers was especially highlighted by delegates from countries which are

developing market economy systems.

The discussions also identified the importance of each jurisdiction’s

cadastral organisation developing its own vision and strategies aligned to its

particular national development aims and priorities. Current management thinking

and skills can be applied in cadastral organisations to achieve purposes and

programs, and provide effective planning and implementation. Each country has to

determine its own vision and directions so that it can align its functions and

programs with the directions and priorities of its government, and with its own

circumstances, environment and stage of development. It is particularly

important that government and national organisation commitment be obtained so

that new systems, technologies and developments are locally owned and accepted,

and that local capacity is made available to sustain them in the long term.

In many countries the main reason for cadastral reform is to promote

political stability, social justice and equity, and economic development. In

countries such as Vietnam, South Africa, Bulgaria, other Eastern and Central

European nations, and Australia, this question is an important justification for

cadastral reform.

The third main group of justifications for cadastral reform has to do with

sustainable management of land resources and protection of the environment. This

question has a direct bearing on cadastral reform as a clear and transparent

system for the distribution of land rights, combined with information and clear

rules of the rights and obligations of a land user and efficient control of the

land use, is considered to be a basic requirement for management of natural

resources. Land tenure reforms are important, for example to stop deforestation

and erosion and to rehabilitate degraded soils. The cadastre is also important

as a source of information and a tool for implementing land use planning. These

questions were particularly important as a justification for ongoing cadastral

reforms in Thailand, People's Republic of China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines,

Republic of Korea, Australia and New Zealand

In several countries, different cadastral systems were developed for

different purposes or through influences from other countries and adopted in

different ways to the traditions existing in the country. Traditional land

tenure systems represent another area of great importance, as all countries

expressed a will to recognise traditional land tenure as a base for formal land

registration. In several countries, the responsibility for land registration is

divided into legal registration of documents and technical registration of the

geographic location and land use of land parcels. The question of

standardisation of different systems is important as a justification of

cadastral reform in nations such as Thailand, Republic of Korea and Bulgaria.

Group titles to incorporate traditional land tenure, but also to solve land

disputes, are especially important in South Africa.

The cadastre has been introduced in many countries in the world with the

primary aim of facilitating the collection of governmental revenue through land

taxation. Today, this is an important reason for cadastral reforms in Malaysia,

Thailand and the Philippines, especially as a means of strengthening local

governments.

Reforms motivated by the desire to rationalise cadastral procedures and

organisations, and to make information more accessible with the help of modern

technology, were reported from the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Sweden. In

Cambodia and Vietnam, the wish to computerise the cadastre in order to speed up

the reform and facilitate access and reliability of the data is a strong driving

force. Costs for land registration need to be reduced, at least for some types

of land tenure, in South Africa. In Malaysia, computerisation is seen as a major

solution to their problems, created by frequent use of temporary, qualified

titles. Other motivations reported for cadastral reforms were to prevent land

speculation (Republic of Korea) and to accelerate settlement ownership to

prevent land frauds (Philippines). Almost all countries mentioned that the

question of migration from rural to urban areas also is a driving force for

cadastral development.

The success of cadastral reforms is demonstrated in substantially increasing

food production in Vietnam, and in increasing real property values,

productivity, access to credit and general economic activities in Thailand. Lack

of reliable cadastral records often is compensated for by society through the

development of informal markets and rules. This may create unstable conditions,

and has, in certain locations, resulted in higher transaction costs, higher

interest rates (or no possibility for credit) and lower land values compared to

areas with reliable cadastral records. Other negative impacts such as

unsustainable land use and degradation of soils have also been associated with

the lack of an established land management system/reliable cadastral records.

In summary, a number of common justifications for the cadastre were

identified in two or more jurisdictions. These can be grouped into the following

general categories:

(1) Supporting the Creation or Development of an Efficient Land Market

The elements identified included: promoting investment through the provision

of secure title for economic development; increasing revenue for central and

local government by accurate identification of land use activity and property

values; and standardisation of transactions to reduce costs and increase

efficiency through simplifying procedures and unifying different systems.

It was also emphasised that cadastral systems provided a base for effective

zoning and planning, to assist economic decision making, and for the orderly

reservation ahead of implementation of community and national facilities. The

role of the cadastre in supporting lending and the efficient application of

credit was also seen as important.

(2) Improved Protection of Land Rights

This includes the reduction and avoidance of land and boundary disputes; the

establishment of government supported entitlements to land title and associated

rights; the establishment of security; the speeding up of property transfers and

sales; reduction of costs; increased security of land rights and dealings; and

the prevention of fraud in land transactions.

(3) Supporting Land Management and Economic Development

This includes providing better information for land planning and better

mechanisms for implementing planning policies and improving overall land

administration; accelerated settlement and taking up of individual ownership to

support economic growth; and support for socially desired land use and

environmental considerations.

(4) Computerisation

This is required to reduce costs and provide rapid processing of

transactions, and to increase the accuracy of procedures and improve access to

associated databases.

(5) Simplification of Processes

This is required to simplify procedures and operations, and develop standards

to improve efficiency and user friendliness. There is also a need to simplify

and remove overlaps in the activities of organisations involved in cadastral

functions.

Other general issues arising were the efficient support for traditional

tenures through the provision of Group ownership, support for political

stability through the advance of social justice, and the overall reduction of

the cost of the land registration system.

SESSION 5: LAND MARKETS AND CADASTRAL PROCESSES

“All countries need a formal system to register land and property and

hence to provide secure ownership in land, investments and other private and

public rights in real estate. A system for recording land ownership, land

values, land use and other land-related data is an indispensable tool for a

market economy to work properly.”

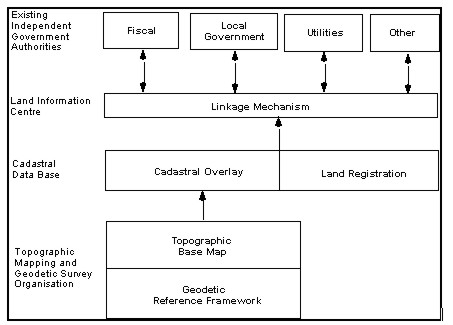

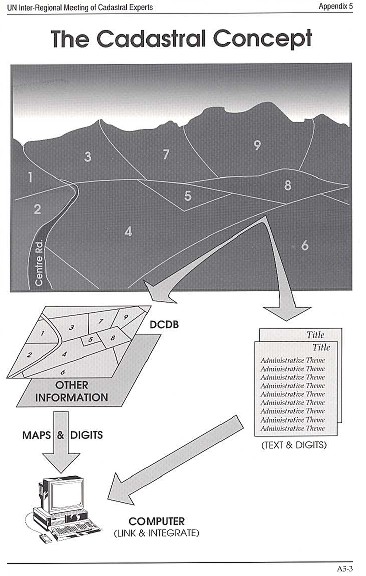

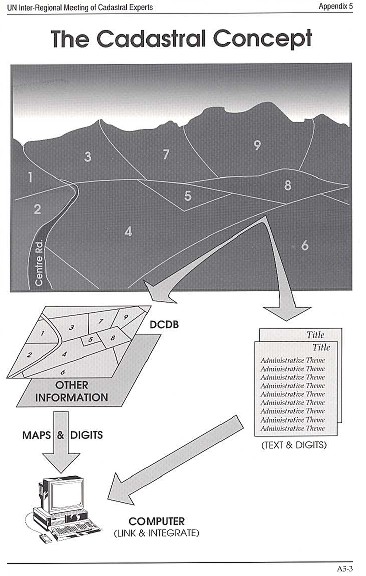

Figure 1. A Statewide Parcel-based Land Information System

Based on a Legal Cadastre.

Land Administration Guidelines, UN Economic Commission for Europe

A great deal has been written and guidelines prepared on land administration,

the cadastral concept and the development of land and geographic information

systems. However what is important is the efficiency and effectiveness of the

systems, and particularly the operation of the land market which involves land

transfer, subdivision, land use and planning, valuation and land taxation. The

key however is the operation of the basic cadastral processes which underpin the

cadastre and related land information systems, and which create and define the

land parcels and the individual land rights which attach to the land parcel.

While recognising the importance of the wider land administration framework,

this meeting will concentrate on the operation of land markets which permit land

rights to be bought, sold, mortgaged and leased, efficiently and effectively. In

particular the focus will be on the three cadastral processes of:

- adjudication of land rights

- transfer of land rights

- mutation (subdivision and consolidation)

In considering the introduction or improvement of land markets, countries

need to discuss:

- are land markets necessary?

- the advantages and disadvantages of adjudicating individual land rights?

- the relationship between systems to record individual land rights, land

use and land values.

SESSION 6: COUNTRY PRESENTATIONS

Statistics

- Total number of land parcels: including roads as parcels, 4.1 million;

excluding roads as parcels, 3.3 million

- Lands parcels with complete cadastral survey, 3.0 million (approx.)

- Land parcels with registered title, 3.2 million (approx.)

- Land parcels with other official tenures (crown land, reserves, leases

etc.), 0.1 million (approx.)

- Land parcels with no cadastral survey and no title (e.g. crown land), <

0.1 million (approx.)

- New land parcels created per annum, 50,000

- Land parcels transferred per annum, 180,000

- Land parcels adjudicated: primary applications, < 100

- % of parcels in urban areas shown on cadastral maps, 100%

Best Aspects

- High level of confidence in the titling system due to government guarantee

and the virtual absence of litigation as to boundaries (23 boundary

determinations per year).

- Titles based on accurate survey executed by surveyors registered under the

Surveyors Act.

- Process enshrined in statutes which include the registration process

traceability of measurement, definition of standards, plan examination and

adjudication.

Aspects Needing Improvement

- System has grown from an isolated surveys approach. There is a lack of

overall mathematical rigour in the cadastral fabric.

- Small number of old system and Crown land parcels still without accurate

survey.

- The map sourced digital cadastral data base is inconsistent in quality due

to the variation of source material. This will be overcome over time by

connections of the existing cadastral frame work to the survey network.

Victoria, Australia (Prof. I. Williamson)

Statistics

- Number of land parcels (80% urban towns, provincial cities and

metropolitan area, 20% rural)

- freehold, 2,400,000 (strata titles, 0.4 million)

- Crown land, 100,000

- Number of parcels with a complete cadastral survey, > 90%

- Number of parcels held under some form of land registration

- Certificate of Title, 2,300,000

- General Law, 60,000

- Number of parcels held under other forms of official tenures (Crown lease

etc.), 50,000

- Number of parcels with no cadastral survey and no title (estimate only -

no official figures), 50,000

- Number of new parcels created annually, 50,000

- Time to subdivide

- without construction, 3-6 months

- with road construction, 12-18 months

- Number of parcels transferred annually, 200,000

- Time to transfer parcels (moving to over-the-counter transfer with full

computerisation), 4-8 weeks

- Number of parcels surveyed, adjudicated and issued with a title or deed

annually, 200,000

- Percentage of parcels in urban areas which are shown on cadastral maps, >

90%

Best Aspects

- The title registration and cadastral survey system supports a very active,

effective and secure land market to permit rights in land being bought, sold,

mortgaged and leased and for land to be subdivided and developed. The system

is virtually litigation free. Land tenure or boundary disputes are virtually

unheard of.

- The cadastral system is operated by a large number of highly trained

professionals who are supported by well established professional institutions

and universities. This is particularly the case for Surveying (1 licensed

professional land surveyor/4,000 population) and Legal professions.

- The cadastral system is highly centralised in one Land Titles Office.

While this could be seen as one of the best aspects of the system, it could

also be seen as one of the worst aspects. Without doubt centralisation allows

a high level of coordination and computerization (Victoria has a complete

digital cadastral data base) while at the same time it has restricted the

availability of cadastral data at a local level.

Aspects Needing Improvement

- The cadastral system is still constrained by historic administrative

arrangements which have their origins from the manner in which Australia was

settled. This particularly relates to a separate Land Titles Office and the

Office of Surveyor General. However recent times have seen the establishment

of the Office of Geographic Data Coordination.

- The cadastral system is based on very accurate isolated cadastral surveys.

The system has historically not used a State-wide coordinate system, nor is it

map-based, although the State is slowly moving in this direction.

- The cadastral system is a relatively complex and expensive system. It is

heavily directed at individual transfers for individual parcels for individual

persons.

Malaysia (Dato’ Abdul Majid)

Statistics (for peninsular Malaysia only, as at December 1995)

- Total number of urban parcels, 2,157,000

- Total number of rural parcels, 6,011,000

- Number of parcels with complete cadastral survey, 5,163,000

- Number of parcels with Final Title (FT), 2,244,000

- Number of parcels with Qualified Title (QT), 2,418,000

- Number of parcels with no survey and no title (e.g. Temporary Occupation

Licences), 586,000

- Number of new parcels created annually, 200,000

- Number of parcels transferred annually, 1,500,000

- Number of parcels surveyed and issued with Final Title annually, 150,000

- Percentage of parcels in urban areas shown on cadastral maps, 65%

Best Aspects

- Indefeasibility of title and rights - ownership is guaranteed by the

government.

- Transactions are simple, unambiguous and inexpensive.

- Accurate land demarcation minimizes overlapping ownership and litigation.

Aspects Needing Improvement

- The registration of titles and surveys are done by different departments.

This results in duplications, red tape, delays and backlog in the registration

of FT.

- The provision for issuance of QT prior to final survey has resulted in 2.4

million QT’s that are yet to be converted to FT.

- Expensive.

Guangdong Province, People's Republic of

China (Madam Yixi Liang)

Statistics (People's Republic of China)

- Largest population in the world, 1,200 million.

- Population density of 125 persons per Km2.

- Total land mass of 9.6 million Km2. (1/15th of the world’s area, and 1/4

of Asia).

- Per capita land area, 0.8 Ha.

- Per capita cultivated area, 0.09 Ha.

- People's Republic of China feeds 21.8% of the world’s population, with

only 6.8% of the world’s cultivated area.

- Landownership characteristics:

- socialist public ownership is adopted for all land

- 2 forms of public ownership: by the whole people, and by collective

ownership

- Present cadastral management functions are: land use inventory, city and

town cadastral inventory, and land condition inventory.

- National soil survey has been completed.

- Land registration started in 1988.

- A unified system of registration and certification of land rights will be

established in the People's Republic of China in 2 years.

Statistics (Guangdong Province)

- Land Department for Guangdong Province established in 1985.

- Land administration tasks in the Province: cadastral management; land

utilisation; administration of land use for construction, surveying, and place

names.

- Land use inventory conducted using aerial photography, orthophotos, and

1:10,000 topographic maps.

- 1:10,000 topographic map or orthophoto map coverage of the Province is

complete.

- Since 1985, cadastral inventory of 1,271 towns (77.5%) and 84,406 villages

(68.1%) has been completed.

- Land registration and certification completed for 1,956,000 state-owned

parcels and 8,168,000 collective land parcels since 1988, giving a

certification percentage of 75%.

- In day-to-day cadastral management operations, since 1993 there have been

155,000 transfers, mortgages and land use changes handled.

Bulgaria (Dr Tatiana Ouzounova)

Statistics

- Area of 111,000 Km2, with 58% being agricultural land.

- 279 municipalities.

- Population of 8.5 million.

- 5,000 settlements.

- Engaged in moving from socialist political system and a centrally planned

economy to a Western style democracy based on a market economy.

- Land reform is a key element of the transition, involving land policy,

land tenure and land administration.

- Emphasis is on land tenure based on individual rights.

- Property rights for 5.4 million Ha of farming land to be restored.

- Rights will be restored to 2.4 million citizens to over 8 million parcels.

- As at 31/12/1995, property rights to 57% of farming land have been

restored.

- Estimated that by end of 1996, 84% of land will have been returned to

owners.

Speculative Statistics

- 9.2 million people in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, 26% in

informal settlements.

- The largest urban area in KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 24% is informal (124,284

informal dwellings), housing half a million people.

- 7 million is informal settlement population of the whole of South Africa.

Best Aspects

- Every legal parcel of land subdivided and/or transferred is linked to the

national geodetic network

- This limits encroachment and boundary conflict problems.

- Through surround surveys, linked to the geodetic network, it will be

possible to introduce less accurate surveys within the outside survey, either

unintentionally (Development Facilitation Act) or intentionally.

- Makes an LIS more sustainable and cost efficient and when up and running

will underpin the land reform programmes.

- Every legal parcel of land subdivided and/or transferred, since the 1930s,

has been registered and held as a record in a public office (Surveyor General

and Deeds Registry)