Enhancing Professional Competence of Surveyors in EuropeStig Enemark and Paddy Prendergast (Ed.)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ContentsPaddy Prendergast Stig Enemark Rob Ledger Hans Mattsson Frances Plimmer Appendices B Table of Academic Courses producing Geodetic Surveyors in Europe C Educational Profiles at Universities Investigated D FIG Definition of "Surveyor" E Questionnaire on Threshold Standards for Professional Competence F Programme of the Joint CLGE /FIG Seminar in Delft University of Technology on 3rd November 2000 Executive SummaryStig Enemark and Paddy PrendergastIntroductionThe International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) established a Task Force on mutual recognition of qualifications/reciprocity in 1997, in order to investigate the concept of 'standards of global professional competence' for surveyors. FIG recognised the need due to international market pressures and the introduction by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) of regulations to liberalise trade in services. The intention is to review the area of mutual recognition of qualifications within the world-wide surveying community and develop a framework for introduction of standards of global professional competence in this area. It is FIG's aim to drive these developments instead of being driven by them, and the work of the task force was seen only as the first step in this direction. FIG will launch a final report including a policy statement on Mutual Recognition at the FIG Congress in Washington, April 2002. In parallel to the FIG initiative the Council of European Geodetic Surveyors (CLGE) established a working party to develop a 'core syllabus' for geodetic surveying early in 1998. The concept was to try to identify a core syllabus detailing the technical subjects and levels, which should be common in all academic courses producing geodetic surveyors. The intention for the report on the core syllabus was to provide:

These two objectives were ultimately about enhancing professional competence of surveyors. The European models in this area were examined through some research grants awarded by CLGE during 2000. Furthermore, it was seen as an ideal issue for merging the efforts of CLGE and FIG. The objectives were dealt with at a joint CLGE/FIG seminar held at Delft University of Technology in November 2000. This was a significant event since this was the first time that CLGE and FIG have formally collaborated on a project. We hope that this will be setting a precedent for the future. BackgroundThe rights of EU citizens to provide services anywhere in the EU are fundamental principles of EU law. National regulations, which only recognise professional qualifications of a particular jurisdiction present obstacles to these fundamental rights. These obstacles are overcome by rules guaranteeing the mutual recognition of professional qualifications between Member States, i.e. the Sectoral and General Directives. The Sectoral Directives deal with specific regulated professions (physicians and specialists, general nurses, dentists, midwives, veterinarians, pharmacists, and architects). The General Directives introduced in 1989 and 1992 deal with qualifications obtained through programmes of higher education (89/48/EEC), and with qualifications obtained through secondary vocational education and short programmes of higher education (92/51/EEC). The European Commission carried out a review of these Directives during 2000 due to a perception that little progress has been made implementing procedures for mutual recognition of qualifications since they were introduced. Consequently, it was opportune that FIG and CLGE were jointly investigating the issue from the surveying perspective at the same time. Traditionally, the regulated portion of the surveying profession predominantly operated in niche markets, which were either local or national in character. These regulated markets are not conducive to mobility of professionals, due to the wide variety of procedures, laws, and functions performed by surveyors. However, the non-regulated portion of the surveying market is highly conducive to mobility, and has been quite successful with mobility of personnel during the last decade. Seminar in DelftA joint CLGE / FIG seminar on Enhancing Professional Competence was held on 3rd November 2000 at Technical University in Delft in the Netherlands. Initial results from the following research projects were presented:

The intention of the seminar was to widen the debate among the academic surveying community in Europe and to provide an opportunity to include their opinions and ideas. The seminar was by invitation only and attracted some 50 participants from 17 countries representing the educational sector and the professional surveying community in Europe. The seminar was very successful and has generated many articles in national surveying journals in Europe. We now hope that the final results of the research projects contained within this report will stimulate further discussion on this important subject. We do not consider the seminar or this report to be the final answer, but only the beginning of a process to investigate and debate these issues more widely, and to provide us with the knowledge to allow us choose good policies for the future of our profession. It is anticipated that the outcome of this report will then form the basis for the development of a world-wide model by FIG. ConclusionsIt seems evident from the debate in the seminar that "the only constant is change" and that we must continue to ensure that our graduates are educated for a changing profession in a changing market. It is important to provide future surveyors with the necessary professional education and training and the administrative procedures to work anywhere in Europe. While our marketplace is, currently Europe, there is a clear indication from the World Trade Organisation that the marketplace will soon be global. There was a clear indication of a future educational profile composed by the areas of Measurement Science and Land Administration and supported by and embedded in a broad interdisciplinary paradigm of Geographic Information Management. There was also a clear indication that a better understanding of different educational and competence models can establish a general improvement of the educational base and enhancement of professional competence in the broad surveying discipline throughout Europe, and also on a more global scale. The primary objective of the Bologna Agreement was to establish and promote the European system of higher education world-wide. This will only be successful if the basic underlying principles for education promoted in Europe are of a sufficiently high standard. There is a danger that the BAC + 3 threshold is too low as a basic professional qualification and that the quality of existing professional qualifications in Europe will be eroded, thus hindering the overall objective of the European Ministers of Education. One way of predicting future needs is by observing the development of the profession, so that decisive changes can be discovered at an early stage and distinguished from more transitory events. Another way of broadening the basis of assessment is by considering developments in other countries, in both education and practice. Given the internationalisation, which has taken place, not least in Europe, there is every possibility of both professional and university representatives actively sharing one another's experiences. The so-called "Allan Report" published by CLGE, has shown how complex reality is, but also how eventful. Presumably our concern should be with encouraging educational and professional dynamism rather than with isolating certain activities. There are a number of barriers, which hinder mutual recognition in Europe. Language, national customs and cultures are, however, not true barriers to mutual recognition and the free movement of professionals which mutual recognition is designed to achieve. Lack of knowledge and fear are the main barriers and yet with improved communication and understanding, these will disappear. We should concentrate, not on the process of becoming a qualified surveyor, but on the outcomes of that process. Mutual recognition, either as a profession world-wide or on a more selective reciprocity basis, becomes simply an issue of investigating the competence of qualified individuals to perform the surveying tasks undertaken in other countries. Inevitably, one of the essentials to achieving the free movement of professionals is the recognition and acceptance by our clients of our particular skills. This can not be dealt with through "internal" restructuring. It is more of a promotional exercise, and it is basically about enhancement of professional competence. RecommendationsIt is recommended that

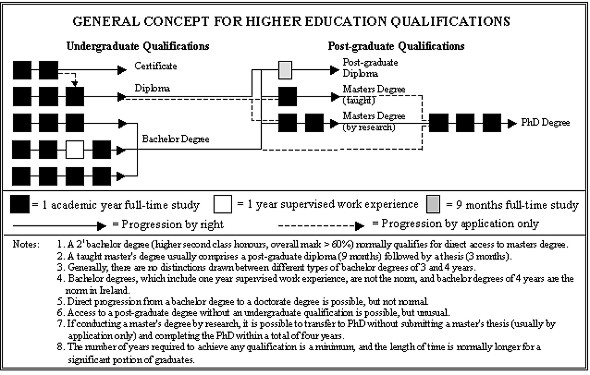

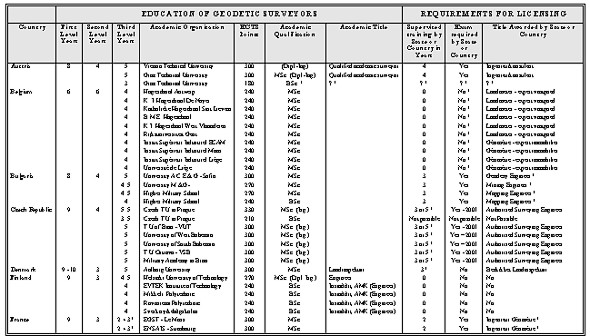

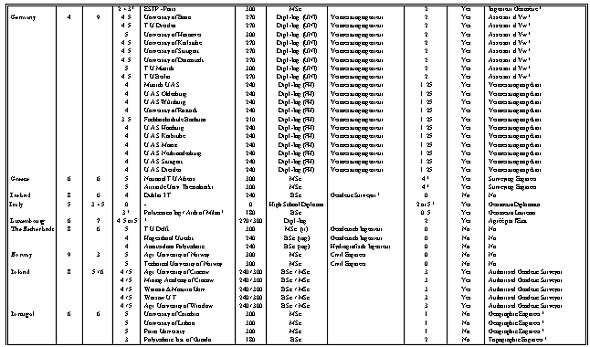

CLGE's Initiative to Enhance Academic Standards for Geodetic Surveyors in EuropePaddy PrendergastAbstractThe diversity of course content and standards achieved in the academic courses producing European geodetic surveyors leads to differences in the range and types of services provided by the profession throughout Europe. The intensive application of technology within surveying during the last 30 years has automated many highly technical procedures. The trend towards liberalisation of national surveying markets, and the development of new international markets due to the EU's internal market policies and the advance of globalisation has demanded new skills of surveyors. All of these factors combined to identify education as the key issue for the future of the surveying profession during a re-evaluation of CLGE's aims during 1999. BackgroundCLGE, (Comité de Liaison des Géomètres Européens, or the Council of European Geodetic Surveyors in English) is the umbrella organisation for national professional associations of geodetic surveyors in Europe. CLGE represents approximately 25000 surveyors in 21 European countries. The term geodetic surveyor is used by CLGE as a collective term to include land surveyors, surveying engineers and géomètres-experts throughout Europe. IntroductionOne of the most obvious traits of the surveying profession in Europe is its market diversity in the different countries. Professional services provided by geodetic surveyors in one EU country may be provided by other professionals in another country. This wide diversity of professional practice has led to a corresponding diversity in academic qualifications for geodetic surveyors. Academic programmes are also primarily focussed on each country's own national surveying marketplace, which puts different emphases on some aspects and includes other areas of study not common to all countries or in all curriculums. This diversity was identified in the early 1980's by CLGE, and an attempt was made to document the range of activities of each national system in a report entitled 'The Education and Practice of the Geodetic Surveyor in Western Europe'. The first edition was published in 1985, and two further editions have since been published. This report, now commonly referred to as the Allan Report after its editor Prof. Arthur Allan of University College London, is very comprehensive, provides information in a standardised format, and includes three charts explaining the situation in each country. The first chart documents the route(s) available for qualifying as a geodetic surveyor. The second lists the academic subjects and their relative amounts completed during the third level academic qualification. The third chart lists the disciplines practised by surveying professionals during their careers. In my view, the report highlights the differences between the countries rather than identifying and analysing similarities. Core SyllabusCLGE established a working party in early 1998 to focus on bridging some of these differences. If geodetic surveyors from the different parts of Europe were ever to be treated as equals by one another and by other professions then we had to try to initiate change in the academic courses producing geodetic surveyors. The initial concept was to try to identify a core syllabus, which detailed the technical subjects and levels, which should be common in all academic courses producing geodetic surveyors. It was also intended that the core syllabus should be flexible enough to permit inclusion of subjects of national importance, such as national property law. I wish to stress that this initiative was not an attempt to harmonise curriculums in Europe. Cultural diversity is one of Europe's strengths, and it was not intended by CLGE for the core syllabus to limit this in any way. The concept was to try to bring diverging curriculum development into parallel streams, rather than try to force them to converge on one common core curriculum. What was needed were some guiding policies or principles to provide a framework for curriculum development. It was also expressly stated that the core syllabus should not represent a minimum standard from the range of existing courses. The concept was to define a high standard to which countries could develop and enhance their existing courses. A main objective of this initiative was to supply information to improve our understanding which would in turn initiate change of national surveying curriculum's and enhance academic standards within Europe. Different Models ExaminedDifferent models were examined by the working party to identify how a core syllabus might be implemented. The accreditation model used by the International Hydrographic Organisation (IHO) and Commission 4 of FIG was investigated initially. A syllabus is specified jointly by the IHO and FIG Commission 4, which academic courses around the world adopt voluntarily in order to acquire IHO accreditation. Academic institutions are then visited on a five-year basis to accredit the curriculum being delivered versus the published syllabus, which is modified regularly to embrace new technologies and methods. CLGE decided not adopt this model at this stage, because although the practice of hydrography internationally operates under a common international maritime law, the same could not be said for the different countries of Europe where different legal systems and standards apply. Two other difficulties with this model were that a) curricula are set by national or state administrations in some European countries, which might not readily accept the accreditation concept, and b) CLGE does not currently have the resources to operate such a model. CLGE may need to re-examine this model in the future. Another model examined was the ISO/TC211/PT 19122 proposal to establish an ISO standard for the Qualification and Certification of Personnel for Geographic Information/Geomatics. This model was considered too rigid in that a content definition for an academic qualification would prove to be too difficult to modify once adopted as an ISO standard. The working party felt that curricula should be constantly amended to match the dynamic nature of the surveying market. "The idea that there is one best way of doing things that will last through time is ludicrous, especially in an environment that is changing so rapidly" (Dale, 2000). Secondly, the ISO proposal focuses specifically on geographic information management, which links the measurement science and land management areas of our profession. The effect of the ISO proposal would be to fragment the surveying profession by carving out the emerging central area of surveying practice for a new profession. This proposal was considered both undesirable and unworkable in practice. The model adopted by CLGE was to produce a core syllabus as guidance for directors of academic courses producing geodetic surveyors. There should not be any coercion in the implementation of this guidance. The core syllabus was to be a consensus supported by the majority of the national associations of CLGE, and as such would carry a certain weight. CLGE did not wish to encroach upon the academic independence of course directors, who are already well informed of national requirements. However, CLGE hoped to provide some advice and guidance on requirements at international level in Europe. Difficulties in developing a core syllabus began with an examination of whether courses should be assessed on input (i.e. the specific subjects and time devoted to them within the syllabus) or on output (i.e. the range of skills achieved by the graduate). There was a difference of opinion between the working party members on this issue. Some held the view that courses should only be assessed on the competence of graduates produced, while others held the view that the input system had the added benefit of supplying much needed basic guidance to course directors, especially for countries which needed assistance to develop their curricula. Research GrantsCLGE decided in Copenhagen in April 2000 to provide research grants to investigate both of these issues, and eminent European academics were chosen to conduct the research. Dr Frances Plimmer, University of Glamorgan in Wales was contracted to develop threshold standards and a methodology to assess the competence of surveying professionals. Prof. Hans Mattsson, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm in Sweden was contracted to examine the different models used in Europe for surveying courses with respect to curricula content and curricula delivery. Finally, Rob Ledger, Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors in the United Kingdom who was the leader of the CLGE working party investigating the concept of a core syllabus was contracted to complete the definition of the core syllabus. All three presented interim results of their research to the joint CLGE / FIG seminar at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands on 3rd November 2000, and ideas and feedback from the floor were collected. This joint report presents the final results of the research conducted under all three strands. Education Identified as KeyEducation was identified as the key issue for the future of the profession during a Re-evaluation of CLGE's Aims during 1999. One main reason why education was singled out was to provide geodetic surveyors with the skills and abilities necessary to allow them to adapt to the rapidly changing commercial environment in Europe. Traditionally, the surveying profession predominantly operated in niche markets, which were either local or national in character. Consequently, academic courses in different countries were adapted specifically for these local and national requirements without any reference to the needs of the international markets in Europe or globally. The EU have been developing a new international market in Europe via its internal market policies, and many central and eastern European countries have been progressively implementing market economies during the last decade. A wider international market at global level has also been rapidly developing recently, and regulations for these international markets in services are currently being negotiated in the GATS negotiations at the WTO in Geneva. The perceived effect of these negotiations is the opening of international markets outside Europe at the cost of increased liberalisation of the national markets within the EU, whereas in truth they are laying the regulatory framework for conducting international business in services. Enhancing the professional competence of surveyors is now urgently required to provide the skills necessary to exploit these new opportunities, and to optimise the effects of legislative reform at national and European level. All of these developments indicate that there is now an urgent requirement to refocus academic programmes producing geodetic surveyors on the needs of international markets as well as the traditional local and national markets. A second reason why education was identified as the key issue for the future of the profession is the intensive application of technology within surveying during the last few decades. New skills are required to exploit new data sources and make use of new methods, not only in an efficient manner, but also to ensure that the consequences of particular choices or actions are fully appreciated. "We should not thrust the black box, we should know what it is doing". The nature of our surveying business is changing and new opportunities are developing, such as in geographic information management, but other professionals are competing with us for these new opportunities. Surveyors have to prove their merit to maintain their foothold in these emerging areas, and they will need new skills to assist them. Many new projects are designed and managed by multi-disciplinary teams of professionals for which surveyors need equality of qualifications and management skills to allow them to participate effectively as equals. Curriculum changes, which are focussed and well designed, can provide these skills. These were two of the main reasons why education was identified as a critical issue for the future of the profession. The concept of a core syllabus was to deliver advice for course directors in identifying the skills required from the wider international perspective, and then provide guidance on a model curriculum to supply those skills. Mobility of ProfessionalsA secondary aim of the core syllabus initiative was to facilitate the mobility of professionals between European countries using the EU concept of mutual recognition of qualifications. The rights of EU citizens to provide services anywhere in the EU are fundamental principles of EU law. National regulations, which only recognise professional qualifications of a particular jurisdiction present obstacles to these fundamental rights. These obstacles are overcome by rules guaranteeing the mutual recognition of professional qualifications between Member States: the Sectoral and General Directives. The Sectoral Directives deal with specific regulated professions (physicians and specialists, general nurses, dentists, midwives, veterinarians, pharmacists, and architects). The General Directives introduced in 1989 and 1992 deal with qualifications obtained through programmes of higher education (89/48/EEC), and with qualifications obtained through secondary vocational education and short programmes of higher education (92/51/EEC). Educational StandardsThe General Directives have introduced the view within the EU that a professional is someone with a 'BAC + 3'qualification. The abbreviation 'BAC' is short for baccalaureate which means the final exam at the end of secondary level education, which should not be confused with bachelor degree at third level, and '+ 3' means a third level qualification of at least three years duration. Therefore 'BAC + 3' effectively means a third level qualification of three years duration (i.e. a bachelor degree). However, the EU 'BAC + 3' view of a professional is not coincident with the existing situation within geodetic surveying education in Europe (See table in appendix B). The existing norm for geodetic surveying education is a master's degree of over four year's duration. This table also highlights some other interesting facts. The length of time required in education to produce geodetic surveyors varies from 15 to 19 years across Europe. Military service is also required in some countries, which results in surveyors not graduating until they are well into their mid twenties. Master's degrees are achieved after 16 to 19 years study (mean 17.4 years), and a bachelor degree is achieved after 15 to 18 years study (mean 16.3 years). In two countries, the Netherlands and Ireland, bachelor degrees are awarded having studied for longer than the European norm for achieving a master's degree. Surveyors with a bachelor's degree might consider themselves disadvantaged if they wish to practice in a country where a master's degree is the norm. They will most likely have to complete some period of extra study or undergo an acceptable period of relevant experience before being accepted as a member of a regulated profession. Another fact highlighted is the range of professional titles being used by geodetic surveyors in Europe. If the profession is to treat realistically the whole of the EU as a single market, then there is a need from the general public and our clients' perspective to adopt an easily recognisable title for all geodetic surveyors in Europe. We should re-examine the term 'geodetic surveyor', adopted by CLGE in 1995, to ensure that this is the correct choice (i.e. the most suitable from a marketing perspective rather than an accurate one). It should be a term to encompass professional services in the areas of measurement science, land administration management and spatial data management. We should also be careful not confuse the issue by using multiple terms (i.e. geodetic surveyor and géomètre). This variety of existing qualifications for geodetic surveying highlights the need for an educational guiding policy or principles across Europe as a whole, not only in surveying, but generally. Bologna AgreementThe European Ministers of Education met in Bologna in June 1999 to agree a set of general principles and to set out a vision for education in Europe for the next decade. They issued a joint declaration on The European Higher Education Area to co-ordinate their educational policies to achieve the adoption of a system of easily comparable degrees in Europe within the first decade of the 21st century consisting of undergraduate and post-graduate cycles. The Bologna declaration is initiating rapid educational reform in Europe and has introduced the concept of a new undergraduate qualification at bachelor degree level in many European countries. Figure 1 provides a generalised concept of higher educational qualifications based on the Bologna model. It attempts to distinguish between the two cycles identified in the Bologna Agreement (undergraduate and post-graduate degrees), and also outlines possible routes of progression and the minimum number of years required for each qualification. There is potential for confusion within the model provided, due to the variety of bachelor and master's degrees available. It is possible within the model to qualify with a master's degree within 4, 5 or 6 years, which may cause practical difficulties when determining equivalence of qualifications for mutual recognition. Preferably, there should be a significant difference in level between a bachelor and a master's degree to distinguish and emphasise the quality of the qualification awarded. This distinction will be blurred if the period taken to complete a master's degree after a bachelor degree is too short and thereby belittles the achievement. Also, six years for achieving a master's degree might be considered too long for producing professionals from an efficiency perspective, whereas five years, which is the existing norm, would seem to be ideal. This suggests that a 3 plus 2 model would be optimal to achieve an appreciable difference in standards between the two degrees, and to promote a concept of a broad-based education to undergraduate level and to introduce specialisation only at post-graduate level. The surveying market is changing so rapidly that a broad education is absolutely necessary to provide graduates with a range of skills to prepare them for a profession, which will change dramatically during their careers.

Figure 1 - Distinguishes between undergraduate and post-graduate qualifications and outlines a general concept for the Bologna Agreement, modelled on the existing Irish situation. Some national professional associations in western and central Europe are beginning to perceive the Bologna Agreement as a threat to the high quality of their existing qualifications at MSc. level, and the high standard required for membership. This feeling is compounded by the EU's notion that a professional is someone with a 'BAC + 3' qualification, when the reality is something quite different. The introduction of many bachelor degrees will generate a lively debate on what practically constitutes a professional. An investigation in this regard in Belgium is suggesting that the technical grade in surveying will comprise graduates with bachelor degrees and the professional grade will comprise graduates with master's degrees. The debate on the issue of what constitutes a professional is of prime importance, and should be discussed by national and pan European professional associations as a matter of urgency. I would suggest that a threshold of four or five years most likely at master's degree level might be the most appropriate for geodetic surveying. It is very important that academic institutions firstly communicate with industry and the national professional associations before any bachelor degrees are introduced. We do not want to have a situation whereby academic institutions are producing graduates on the false assumption that a bachelor degree will qualify the graduates for membership of national associations or access to appointments which were previously reserved for graduates with master's degrees. The European Commission carried out a review of the Sectoral and General Directives during the latter half of 2000 due to a perception that little progress has been made implementing procedures for mutual recognition of qualifications since the Directives were introduced. The adoption of the Commission communication on the future of the mutual recognition of professional qualifications has now been put back to spring 2001, however sources suggest that the Commission does not envisage proposing any change in the 'BAC + 3' threshold at this time. ConclusionsThe primary objective of the Bologna Agreement was to establish and promote the European system of higher education world-wide. This will only be successful if the basic underlying principles for education promoted in Europe are of a sufficiently high standard. There is a danger that the BAC + 3 threshold set by the EU is too low as a basic professional qualification and that the quality of existing European qualifications will be eroded, thus hindering the overall objective of the European Ministers of Education. CLGE has identified the need for a high level education, preferably a master's degree for European geodetic surveyors, which should be broad based to undergraduate level, and specialisation should only be introduced at post-graduate level. Curricula should contain a significant element of measurement science supporting a substantial understanding of land administration management and geographic information management. While it has not been possible for CLGE to produce a core syllabus, as was originally intended, we believe that we have made a significant contribution in highlighting some of the important issues, along with funding research to increase our knowledge in some areas. Curricula must be flexible to provide the skills necessary for a rapidly changing marketplace, but overall guiding principles and policies are necessary to ensure graduates have the competencies to solve the challenges they will meet in their careers. CLGE does not consider this report to be the final answer, but only the beginning of a process to investigate and debate these issues more widely, and to provide us with the knowledge to allow us choose good policies for the future of our profession. I suggest that the issues of "Educational Reform due to the Bologna Agreement" and "What constitutes a professional" are the next most important issues requiring investigation and debate for geodetic surveyors in Europe. ReferencesAllan, A. (1995): The Education and Practice of the Geodetic Surveyor in

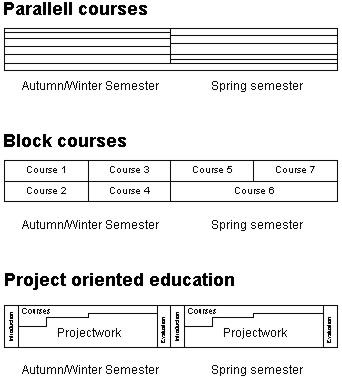

Western Europe, CLGE Report 3rd edition, pp 1-159. UK. AcknowledgementsI would like to give a special word of thanks to all the CLGE delegates and the surveying academics from Europe who attended the joint FIG / CLGE Seminar in Delft in November 2000 who painstakingly corrected the information and provided suggestions for the table included in the appendix. Finally, I would like to specially thank Stig Enemark for his assistance and co-operation arranging the first joint FIG / CLGE seminar on this important subject. Biographical NotesW. P. Prendergast (Paddy) is a lecturer in the Dept. of Geomatics, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland. His main academic interest is the structure and visualisation of spatial data and he is currently completing a PhD in Trinity College Dublin on visual assessments conducted during environmental impact assessments in Ireland. He previously worked in Ordnance Survey Ireland as a military officer on their digital mapping programme throughout the 1980's and early 1990's as part of their senior management team. He has been actively involved in the development of the geodetic surveying profession in Ireland during the last decade and is the current President of the Irish Institution of Surveyors (IIS). He has also been the President of CLGE since 1998. Merging the Efforts of CLGE and FIG to Enhance Professional CompetenceProf. Stig EnemarkIntroductionFIG, short for Federation Internationale des Geometres, or International Federation of Surveyors in English, is the umbrella organisation for national associations of surveyors world wide, representing all surveying disciplines. Nearly 100 countries are represented in FIG covering a total of about 230,000 surveyors world wide. FIG is a UN-recognised non governmental organisation (NGO) and its aim is to ensure that disciplines of surveying and all who practice them meet the needs of the markets and communities that they serve. It realises its aim by promoting the practice of the profession and encouraging the development of professional standards. Educational development and enhancement of professional competence are core issues in this regard. FIG has established working parties on educational issues and currently a Task Force is undertaken in the area of Mutual Recognition. The seminar in Delft was about paving the way to enhancement of professional competence. This issue is seen as ideal for merging the efforts of CLGE and FIG. Issues such as curricula development, quality assurance, and continuing professional development are crucial to any professional organisation at national regional or international level. The issues become even more acute when looking at the challenges facing the surveying profession. Some of these challenges are due to evolution of technology and some are due to institutional changes as a consequence of political and economical development in individual countries. Developments in technology and institutional frameworks may provide new opportunities for the surveying profession, but they will also be the destroyers of some professional work. The challenges of the so-called information age will be to integrate modern surveying technology into a broader process of problem solving and decision making. We must assess carefully what range of skills will be required of those entering, and continuing within, the modern occupational world of surveying. There is no doubt that the main challenge of the future will be that the only constant is change. To deal with this constant change the educational base must be flexible. The graduates must be adaptable to a rapidly changing labour market. The point is, that professional and technical skills can be acquired and updated at a later stage in ones career while skills for theoretical problem-solving and skills for learning to learn can only be achieved through the process of academic training at the universities. Universities should focus on educating for life, not for short term skills. Development, maintenance and enhancement of professional competence should be seen as a total process facilitated through an efficient interaction between education, research and professional practice. International Trends in Surveying EducationManagement skills, versus specialist skills. The changes in the surveying profession and practice and especially the development of new push button technologies has voiced the need for including the core discipline of management as a basic element in today's surveying education. Traditional specialist skills are no longer sufficient or adequate to serve the client base. Surveyors need to have the skill to plan and manage diverse projects, including not only technical skills, but those of other professions as well. In short, the modern surveyor has to be capable not only of managing within change but managing the change itself. Technological developments take the skill out of measurement and the processing of data. Almost any individual can press buttons to create survey information and process this information in automated systems. In the same way, technological developments make GIS a tool available to almost any individual. The skill of the future lies in the interpretation of the data and in their management in such a way as to meet the needs of customers, institutions and communities. Therefore, management skills will be a key demand in the future surveying world. Project organised education, versus subject based education. An alternative to traditional subject-based education is found in the project organised model where traditional taught courses assisted by actual practice are replaced by project work assisted by courses. The aim of the project work is "learning by doing" or "action learning". The project work is problem-based meaning that traditional textbook knowledge is replaced by the necessary knowledge to solve theoretical and practical problems from the society/reality. The aim is broad understanding of interrelationships and the ability to deal with new and unknown problems. In general, the focus of university education should be more on "learning to learn". The traditional focus on acquisition of professional and technical skills (knowing how) often imply an "add-on" approach where for each new innovation one or more courses must be added to the curriculum to address a new technique. It is argued that this traditional subject-based approach should be modified by giving increased attention to entrepreneurial and managerial skills and to the process of problem-solving on a scientific basis (knowing why). Virtual academy, versus classroom lecture courses. There is no doubt that traditional classroom lecturing will be supported by or even replaced by virtual media. The use of distance learning and the www tends to be integrated tools for course delivery, which may lead to the establishment of the "virtual classroom" even at a global level. This trend will challenge the traditional role of the universities. The traditional focus on the on-campus activities will change into a more open role of serving the profession and the society. The computer cannot replace the teacher and the learning process cannot be automated. However, there is no doubt that the concept of virtual academy represents new opportunities especially for facilitating for process of learning and understanding and for widening the role the universities. And the www techniques for course delivery on a distant learning basis represent a key engine especially in the area of lifelong learning programmes. The role of the universities will have to be reengineered based on the new IT-paradigm. The key word will be knowledge-sharing. On-campus courses and distant learning courses should be integrated even if the delivery may be shaped in different ways. Existing lecture courses should always be available on the Web. Existing knowledge and research results should also be available, and packed in a way tailored for use in different areas of professional practice. All graduates would then have access to the newest knowledge throughout their professional life. Lifelong learning, versus vocational training. There was a time, when one qualified for life, once and for all. Today we must qualify constantly just to keep up. It is estimated that the knowledge gained in a vocational degree course has an average useful life span of about four years. The concept of lifelong learning or continuing professional development (CPD) with its emphasis on reviewing personal capabilities and developing a structured action plan to develop existing and new skills is becoming of increasing importance. In this regard, university graduation should be seen as only the first step in a lifelong educational process. The challenge of the new millennium will be to establish a new balance between the universities and professional practice. This new balance should allow the professionals to interact with the universities and thereby get access to continual updating of their professional skills in a lifelong perspective. The only Constant is ChangeA recent survey of the surveying profession in Denmark may be used as a case study to illustrate this constant change. The professional profile of the Danish surveyor is a combination of technical, judicial and design areas. The profile thus is a mix of an engineer, a layer and an architect. The professional fields then consist of three areas: surveying and mapping, cadastre and land management, and spatial planning. Cadastral tasks are the monopoly of licensed surveyors in private practice, and the role of this private surveyor (measuring and wearing green rubber boots) has traditionally epitomised the Danish surveyor. However, the structure of the surveying profession and the profile of the Danish surveyor are both turned upside down through the latest two or three decades. Since the late 1960´s the Danish Association of Chartered Surveyors has carried out a survey of the surveying profession every 10 years starting in 1967. The changes taken place over these 30 years and especially over the latest two decades are quit remarkable. The evolution of surveying profession in Denmark is shown in the figure below.

In 1967 the number of surveyors working in the private surveying firms accounted for about two thirds of the total profession while surveyors employed in the public sector or in other private business accounted for only one third. In 1997 the situation is reversed. Two thirds of the profession is employed outside the private surveying firms. During these 30 years the number of active surveyors is doubled from about 450 in 1967 to about 850 in 1997. This means that the growth is located within the surveyors employed in the public sector or other private business while the number of surveyors working in the private surveying firms has been more or less steady during the last 30 years. Over the same period, the professional profile has changed completely. In 1967 and still in1977 the profile of the Danish surveyor was dominated by the cadastral area while in 1997 it accounts for only 20 percent of the total working hours. In 1997 the distribution was as follows: Planning and Land Management 23 %, Cadastral Work 20 %, Mapping and Engineering Surveys 26 %, and "Other Areas" 31%. Next to the decrease in the cadastral area it is remarkable that the biggest area in 1997 is located outside the traditional working areas. These "other task areas" include general management, general IT-development, and other business developments. The evolution of the professional profile in Denmark is shown in the diagram below.

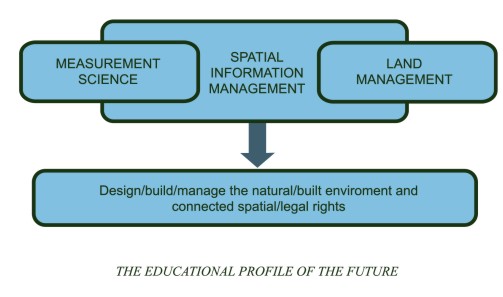

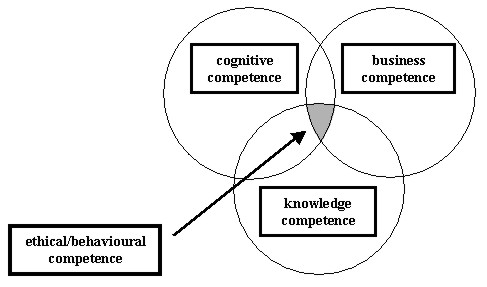

The changes shown above are significant and must of course be reflected in content and structure of the educational base. In fact, the changes have been coped with rather easily within the profession and also with regard to the labour market. It is likely to assume that this is due to the flexible and project organised educational model introduced in 1974 when the surveying programme was moved from the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural Academy in Copenhagen to a new university established in Aalborg. It is also likely to assume that without a flexible educational base being focused on the concept of learning to learn rather than teaching disciplines, and without the deriving adaptability of the graduates being suitable for a changing market, the surveying profession would have faced some heavy problems. The Educational ChallengeThe developments as discussed above have a significant educational impact. There is a need to change the focus from being seen very much as an engineering discipline. There is a need for a more managerial and interdisciplinary focus. The strength of our profession lies in its multidisciplinary approach. Surveying and mapping are clearly technical disciplines (within natural and technical science) while cadastre, land management and spatial planning are judicial or managerial disciplines (within social science). The identity of the surveying profession and its educational base therefore should be in the management of spatial data, with links to the technical as well as social sciences. The universities should act as the main facilitator within the process of forming and promoting the future identity of the surveying profession. Here, the area GIS and, especially, the area managing geographical and spatial information should be the core component of the identity. This responsibility or duty of the universities, then, should be carried out in close co-operation with the industry and the professional institutions. The challenge of the future will to implement the new IT-paradigm and this new multidisciplinary approach into the traditional educational programmes in surveying and engineering. A future educational profile in this area should be composed by the areas of Measurement Science and Land Administration and supported by and embedding in a broad multidisciplinary paradigm of Spatial Information Management. Such a profile is illustrated in the figure below.

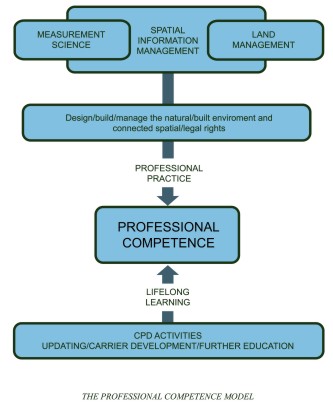

Professional CompetenceThe term professional competence relates to a status as an expert. This status cannot be achieved only through university graduation and it cannot be achieved solely through professional practice. University graduation is no longer a ticket for a lifelong professional carrier. Today one must qualify constantly just to keep up. The idea of "learning for life" is replaced by the concept of lifelong learning. No longer can "keeping up to date" be optional, it is increasingly central to organisational and professional success. The response of the surveying profession, and many other professions, to this challenge has been to promote the concept of continuing professional development (CPD) as a code of practice to be followed by the individual professionals on a mandatory or voluntary basis. Maintaining and developing professional competence is of course the responsibility of the individual practitioner. This duty should be executed by adopting a personal strategy which must be followed systematically. Implementation of such a plan, however, relies on a variety of training options to be offered by different course providers, including the universities. The individual practitioner should be able to rely on a comprehensive CPD concept which is generally acknowledged by the profession and which is economically supported by the industry (public as well as private). Furthermore, the practitioner should have a variety of training and development options available for implementation of his or her personal plan of action. The options should be developed by the universities offering for example one-year masters courses as part time studies based on distance learning; and also by private course providers offering short courses for updating and just-in-time training. These options should be developed in co-operation between the universities, the industry and the professional associations.

Furthermore, the individual practitioner should be able to rely on a comprehensive concept for getting his or her professional competence recognised in a regional and global context. There is an attraction in developing and extending such a principle of Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Mutual recognition allows each country to retain its own kind of professional education and training because it is based, not on the process of achieving professional qualifications, but on the nature and quality of the outcome of that process. In turn this should lead to enhancement of the global professional competence of the surveying profession. And the national associations as well as the universities should play a key role in facilitating this process. In short, enhancement of professional competence relies on an efficient interaction between education, research and professional practice. To facilitate this interaction is the true challenge of the new millennium. ReferencesColemann, D.J. (1998): Applied and Academic Geomatics into the

Twenty-First Century. Proceedings of FIG Commission 2, The XXI International

FIG Congress, pp . Brighton, UK. Biographical NotesProf. Stig Enemark is Head and Managing Director of the Surveying and Planning School at Aalborg University, where he is Reader in Cadastral Science and Land Management. He is Master of Science in Surveying, Planning and Land Management and he obtained his license for cadastral surveying in 1970. He worked for ten years as a consultant surveyor in private practice. He is Vice-President of the Danish Association of Chartered Surveyors. He was Chairman (1994-98) of FIG Commission 2 (Professional Education) and since 1998 he has been Chair of the FIG Task Force on Mutual Recognition. He is an Honorary Member of FIG. His teaching and research interests are in the land policy area including cadastre, land administration systems, land management and spatial planning. Another research area is within project-organised educational and the interaction between education, research and professional practice. He has consulted and published widely within these topics, and presented invited papers at more than 40 international conferences. The idea of a Core Syllabus for Geodetic SurveyorsRob LedgerAbstractThe CLGE working group on recognition of qualifications proposed the concept of a core syllabus in European geodetic surveying to encourage a higher and more relevant common standard of education and to facilitate the mobility of professional surveying labour around Europe. This paper explains why the group feels that this approach may not be suitable for the entire European geodetic surveying sector due to cultural and market diversity. IntroductionIn the spring of 1998, the CLGE established a working party to explore the value of a core syllabus for geodetic surveying in Europe. The initial objectives of the project were to explore how a core syllabus could

and how it could

The original output of the working party (CLGE, 1998), presented at the FIG Brighton Congress in July 1998, suggested that a core syllabus could help to facilitate these objectives. The work of the group over the following two years has now concluded that the creation of a core syllabus is neither the answer to bringing about mutual recognition, nor to enhance professional competence across the entire European geodetic surveying sector. The group believes that the cultural and market diversities that exist across Europe, and also within geodetic surveying itself, mean that a core syllabus could only be useful within certain homogeneous sub-sections of the profession. This paper explains how these conclusions have been reached, and why the objectives of the overall project have subtly changed, now to be encouraging:

Diversity within the European geodetic surveying professionFor a core syllabus to be worthwhile, it relies upon a certain level of commonality across its area of coverage. This commonality must be present not just in the subject areas being taught, but also in the academic and professional framework in which the students are participating. Even if it were possible to identify a set of core subjects in which it was felt to be important for all geodetic surveyors to have a minimum level of competence, it would still be a separate task to work out how that level of competence could be attained in different educational systems, and how it could be certified, if at all. This section looks at both the diversity in the market for surveying services, and the cultural diversity of educational systems across Europe. Market DiversityThe subjects that are covered by a course must primarily reflect the areas of knowledge required by the markets that employ surveying graduates. The problem comes where these markets require different areas of competence, both in the technical subjects in which a graduate must be capable, and also in terms of the business and ethical competencies that they need to show. Furthermore, these market requirements are not static. As time passes, the geodetic surveying market evolves, and courses must adapt their emphases to produce graduates capable of meeting current and future market demands. There are a number of characteristics of the European geodetic surveying market that show how significant market diversity is as a barrier to a core syllabus. The definition of a surveyor is a prime example. Various attempts have been made to define what makes a surveyor (see FIG, 1991), and in an attempt at being more specific, the European Geodetic Surveyor (CLGE, 1997). It is suggested though, that an attempt to compare national customary understandings of the terms "surveyor", "land surveyor", or "geodetic surveyor" against these global or regional definitions would result in some quite major discrepancies. One reason is that certain tasks that are a surveyor's job in one country are part of another professional's remit elsewhere. Where spatial planning is the work of a surveyor in many parts of Europe, some countries have developed an independent profession for spatial planners and although the new profession interacts with surveyors, planning is seen as a separate discipline. Another reason is that some areas of surveying are not practised at all in certain countries. Sometimes this is for historical reasons, but it is often equally true in emerging markets where a country has not yet developed the economic need for a particular surveying service. Cadastre is a prime example of a branch of surveying that is vitally important to most national surveying professions, but for historical reasons is not practised in a small number of countries including the UK. While cadastre would have to be a compulsory and a large part of the education of many European geodetic surveyors, it is only taught as an optional subject on most UK courses, intended for the currently small number of graduates who choose to explore a career abroad. The above two issues still cause a problem where they exist to a lesser degree, i.e. where surveyors do actually pursue a certain area of practice, but only as a minor part of their business. Many course providers will choose not to offer that subject as part of their training as they feel that demand will be low in comparison to the other subjects fighting for space in their curriculum. Cultural diversityLeaving aside the problems concerning the diversity of the markets in which surveying services are offered, there is an equally large issue of contrasting educational models. The CLGE working party found very early on it it's discussions that a core syllabus would struggle to overcome two major issues in European education. The first issue concerns teaching methods, and can be described as the input versus output approach. The second issue involves the method by which a learning provider is able to declare that it is producing graduates with a certain level of competence. This may be thought of as self-assessment versus accreditation. Input versus output approachThe initial CLGE paper from the working party (CLGE, 1998) suggested that a core syllabus could be created which would contain a range of subjects that should be taught, along with a measure of how much time as a minimum should be devoted to each subject. This approach was viewed favourably by a number of European nations, typically those in the South of the region. For many though, the idea of basing a syllabus on what should be presented to students was felt to be inappropriate. Denmark, for example, wanted the emphasis to be placed on the competence with which a student graduated rather than the specific content that they had been taught. It became clear that a system that proposed one method or the other for influencing course content would almost certainly be ignored as unworkable by a large proportion of the intended academic market. Self-assessment versus accreditationA similar cultural diversity exists in the way that academic achievement is perceived by those in industry and the wider profession. The working party initially suggested a method of accrediting those universities that delivered courses based upon the core syllabus, involving some sort of awarding body with the authority to say whether a course was suitable or not. This model is very similar to that operating in countries including the UK where the country's professional body, the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, judges courses against a number of criteria before deciding whether to offer accreditation and therefore a route to professional qualification for its graduates. Again this model was found to be unacceptable in a number of European countries, where a scheme of self-assessment is more normal. Under this system, it is for the university to decide whether its graduates meet a certain standard, and the market is left to determine whether the university's claim is credible. If graduates are at a lower standard than expected, employers will quickly make this clear to the university that trained them. The contrast in the two systems is a result of a difference of inter-relationship between industry, the profession, government and academia in those countries. The factors that influence the content of courses vary in importance across Europe. In some countries, the job market is the driving force of course content. In other areas, professional accreditation, or government funding may be more of an issue. Cultural and market diversity leads to curricula diversityThe issues of cultural and market diversity raise three issues then for a core syllabus:

Having raised the potential difficulties with these issues as expressed earlier in this section, the working group were asked to investigate whether the creation of a core syllabus would be possible across geodetic surveying in Europe, in effect judging whether market diversity was too large or not. The working group needed to determine somehow which subjects should be contained in all course syllabuses. The initial approach taken was to study which subjects were currently being taught by a sample of universities as part of their geodetic surveying courses. The group would then need to decide which subjects being taught reflected what should in fact be taught by everyone. The group pursued the first step by initially studying the syllabuses of geodetic surveying courses from six countries around Europe. The study also included a comparison of the syllabuses of seven courses from the UK to examine specialist rather than regional focus. The study was limited in the sense that certain universities were more forthcoming than others in the amount of syllabus detail that they provided, but it still gave a strong indication that much diversity exists. Within the UK, there was a distinct division between the contents of traditional "land surveying" courses and those focused on geographical information science. Where the former all considered geodesy, engineering surveying, physics, mechanics and instrumentation to be essential, the GI courses preferred to include computer science, software development, and data management. The subjects common to all courses were limited to topographic surveying, statistics, photogrammetry and remote sensing. A core based on these common subjects within the UK would be extremely limited in its use. This is hardly surprising, as the expected job profiles of the graduates from these courses are very different, despite all falling within the definition of geodetic surveying. Comparing course content across Europe also showed significant diversity. Cadastre was again a prime example of a subject fundamental to the syllabus in many countries, yet completely absent in others. What emerges is that there are certain groups of countries that have quite similar educational content, based on the fact that they have comparable markets for surveying services. Parallels can be drawn between course content within Germany, Austria, Switzerland and France, countries' whose liberal professions show strong similarities. The UK and Ireland also appear to offer similar content to students, reflecting two surveying markets quite close in their demands on skills. It might be a more practical starting point for developing core syllabuses for groups of countries with similar market demands rather than the diverse European market. Indeed if these groups with common market demands also have less of a cultural diversity in terms of education and its relationship with the profession and industry, they would appear to be well suited to greater co-ordination in their learning systems. Whether smaller sub-sections of the European geodetic surveying market working together to define standards is beneficial to Europe as a whole is a question for further investigation. How can the original objectives be facilitated?The core syllabus project started out by trying to research how the profession across Europe could facilitate two things:

Whilst the working group has come to the conclusion that a European core syllabus is not the answer to meeting these goals, the goals themselves are still extremely valid. The group agreed that more research was needed in two areas: Evolution of curricula in recognition of market demandInstead of defining what subjects are important to be included in all surveying courses, it may be more productive to acknowledge market diversity and to recognise that the issue for course providers is how they can deliver a course to meet a particular market demand. If market demand differs around Europe and even within single countries, each course will need a slightly different approach and type of content. A gap between market demand and academic supply could be caused by a lack of understanding of how to meet that demand. To assist in overcoming this gap, research is needed into how successful surveying courses have evolved their content and delivery to provide graduates with the skills and learning ability that the market requires. This type of information should be a valuable resource for universities looking to evolve their courses in the right direction. Professor Hans Mattsson addresses this issue in his paper "The Education and Profession of Land Surveyors in Western Europe" (Mattsson, 2000). Mutual RecognitionTo gain a better understanding of how qualified a surveyor is to practice in another country, it should not be a simple case of comparing academic qualifications. While it is undoubtedly important to understand what a graduate has learnt as part of their degree course, it is more useful to potential employers and those offering recognition to a migrant to understand the individual's overall professional competence. A surveyor's ability to work as a professional depends not just on their technical competence but also on their business experience, their ethical standards, and a number of other less obvious factors. Dr Frances Plimmer looks into this matter in her paper "Professional Competence Models in Europe" (Plimmer, 2000). ConclusionsFor a core syllabus to succeed in leading a profession towards a high common standard of education and simpler transferability of labour across borders, there needs to be a relatively high level of commonality within not just the areas of competence that the market demands, but also in terms of education systems, and the inter-relationship between education, industry, the profession and government. The CLGE working party on recognition of qualifications believes that this level of commonality is not present across the whole of the European geodetic surveying sector. There is significant diversity in market demand for surveying services, not just across Europe but also within individual countries. There is a divide in how courses are delivered, and also in how they are recognised as achieving a certain standard. To enable courses to evolve their content to meet European market demand, it is suggested that more information should be published on how successful courses change their focus and content to reflect market changes. To facilitate mutual recognition of qualifications, the profession should work towards a clearer understanding of professional competence and how it can be compared across borders. ReferencesLedger, R. (1998): Discussion on the Development of a Core Syllabus for

European Qualifications in Geodetic Surveying, CLGE Discussion Paper for FIG

Congress in Brighton, pp 1- 22, UK. Biographical NotesRob Ledger is the Head of New Media at the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) in London. A qualified land surveyor, he was previously in charge of Geomatics at the RICS. Rob has until recently been one of two UK delegates to the CLGE, leading the Council's working party on the recognition of qualifications and competencies. Educational Profiles for Land Surveyors in Western EuropeProfessor Hans MattssonAbstractUniversity study programmes for land surveyors differ a great deal from one place to another, and the range of courses related to such core subjects as technical surveying, land management and real estate economics likewise varies considerably. This is borne out by the present article - a study of educational profiles for land surveyors in eight Western European countries. Finding a standard programme of education common to all European states is therefore likely to be impossible and is perhaps not even desirable. Instead, one can draw on the experiences of different universities for guidance concerning educational changes. The present article, then, aims to provide a better understanding of the wealth of variation in European land survey studies. BackgroundThe purpose of this study is to identify what characterises land surveyor education in Europe. The focus of attention will be on curricular content, but some attention will also be given to educational models and to methods of quality assurance. How surveyors are described varies and is subject to change. In this article all types of surveyor whose work is connected with land will usually be referred to as land surveyors. The basis for this decision is that this historically rooted name is the only one I have been able to find which, in my opinion, covers all activities relating to both surveying and real estate. Profession and educationTechnical professions are not usually very well defined in terms of professional practice, and, given the increasing changeability of the world at large, this is not surprising. It is not only the prospect of taking on new challenges, but also technical changes themselves that determine what a profession involves itself with. Increasingly complex technology can give those with an insight into its basic elements an advantage when handling new information and ideas. Simplified technology, on the other hand, means that advanced working methods can be taken over by others, perhaps even by the so-called 'man in the street'. However, some professions also work within a clearly defined framework, and this will have considerable bearing on the way they operate. In some cases, the right to do or not to do a certain type of work may hinge entirely on what is legally permitted. Professionals often form interest organisations for the promotion of their common interests and as a means of keeping each other informed of progress and new developments in their professional field. But interest organisations also have a way of defining the professional agenda, in that their statutes encourage certain activities and discourage others. Active, open interest organisations are probably a matter of necessity for a living profession. Another important aspect of the profession is the education on which it bases itself. Education lays a platform for determining those tasks that can easily be mastered by professional practitioners, those that can only be learned with difficulty later in life and those in which any progress at all is practically impossible. Individual, personal differences can, of course, facilitate or impede, but, in principle, education is of fundamental importance to professional life, even in a rapidly changing world. One question that immediately arises concerns the way in which study programmes are designed. Are they to be tailored to meet the precise needs of the profession; are they to merely point the way the profession should go or are they to specialise in fields where science is strong, leaving the propagation of other knowledge to professional life or the profession itself? These are difficult choices for educational establishments to make. A study programme which lacks relevant content will presumably find itself with no students at all, inferior students or discontented students, because students soon become dissatisfied if they see that the programmes they are following do not match the requirements of the job market. Discord can also occur between education and profession if the knowledge and expertise provided is insufficient or inadequate and cannot be easily acquired in practice. A profession must be able to recruit the people it needs, or it will wither away and other, more relevant groups, will take over instead. The surveyor's profession and education in EuropeThe tasks of the surveyor's profession vary a great deal in the different European countries, just as in other parts of the world, but the profession can be said to originate in mapping and in the definition of boundaries for real estate units and other spatially based rights. The emphasis on these activities, however, varies between countries and also from one period of history to another, and it is not automatically the surveyor who always has responsibility for them, least of all for property formation. The interesting point, though, is that an original knowledge of real estate has enabled the surveyors to develop new activities such as legal counselling, planning, land development, property valuation and property management. Meanwhile technical progress has been rapid. Internationally, then, the surveying profession, as a whole, has a wide range of professional practices that can change according to how readily new tasks can be assimilated. The breadth actually existing is reflected by FIG's definition of surveyor and also by all the commissions into which FIG has divided itself (FIG 1991). The varied nature of the profession is also reflected in a report compiled by Professor Arthur Allan in 1991 and again in 1996 (Allan 1996). He asked surveyor associations in 17 western European countries which activities their members handled and how great was their responsibility. Because his remit in 1996 came from the CLGE, his survey that year excluded all forms of surveyor with no technical surveying competence. This was at a time when the CLGE was developing the term Geodetic Surveyor to segregate it from other types of surveyor. Gradually, though, the CLGE has become more open to the diversity of the profession, as witnessed by its description of the professional fields (CLGE 1996). The abundant variety is also reflected by figure 1. In certain countries, land surveyors are mainly concerned with measurement and mapping, partly related to cadastral questions (e.g. in Austria, Greece and Portugal), while in other countries they have more varied duties which include measurement and real estate knowledge generally (e.g. in France, Germany and the Nordic countries). By the same token, study programmes for surveyors in Europe are variously composed. This, too, is pretty clear from Allan's report (1996), and also from the upgrading devised by the CLGE (fig. 2). In Allan's report, it is possible to find a congruence between education and profession, although in some countries a certain discrepancy can be glimpsed (Mattsson 2000, compare also figures 1 and 2).

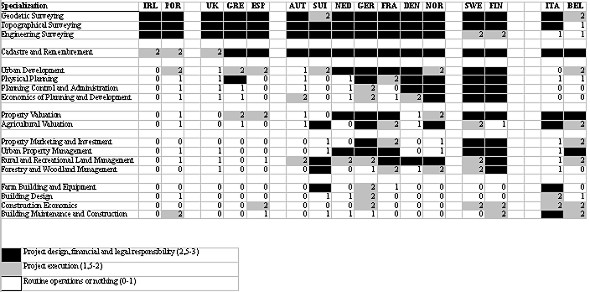

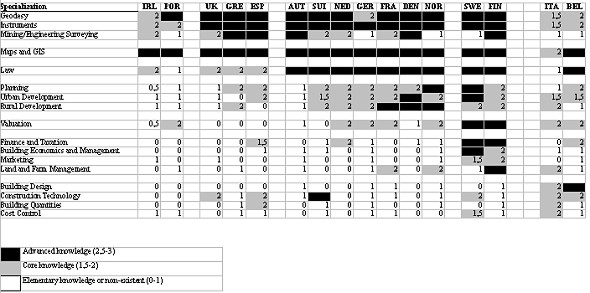

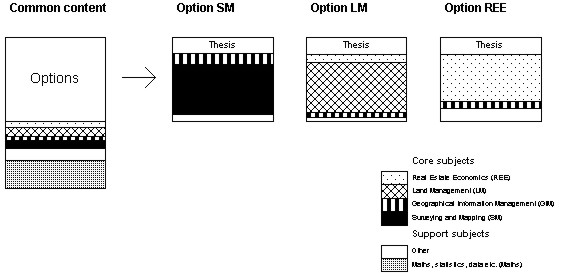

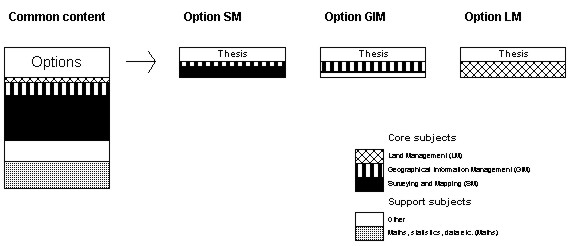

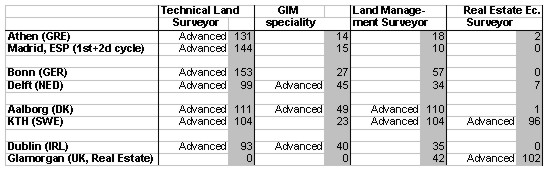

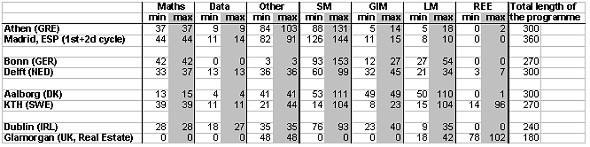

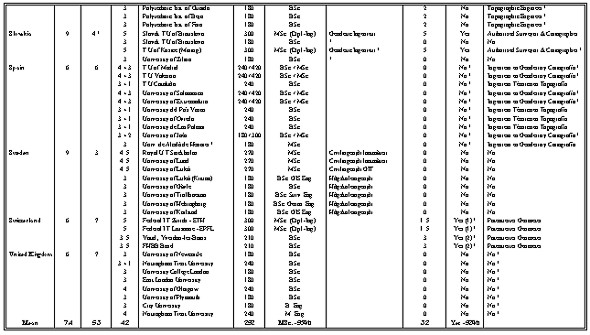

Figure 1. Professional activities in Western Europe. (Source: CLGE 2001, Mattsson 2000 and Allan 1996 for Belgium, France, Germany and Portugal)