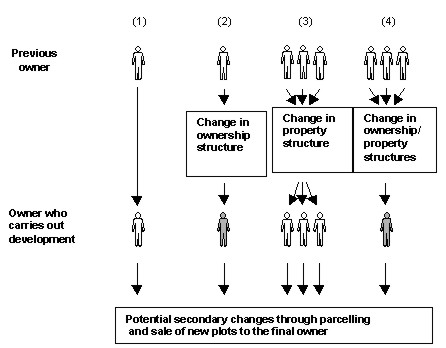

THE FINNISH URBAN LAND READJUSTMENT PROCEDURE IN AN INTERNATIONAL CONTEXTProf. Kauko VIITANEN, FinlandKey words: Urban land readjustment, land development, joint development, land management, land use planning, plan implementation. 1. INTRODUCTIONThe aim of urban land readjustment is to produce new building land and to reorganise urban areas. The method used is designed to consolidate a group of adjoining land parcels for their unified planning and subdivision in an area with a fragmented or an otherwise inappropriate property and ownership structure. Should the land readjustment procedure be inappropriate or unavailable, similar processes are usually undertaken on a case by case basis either through voluntary conveyances or through enforcement (expropriation). Sites will not be made available for building until the property and ownership structures are adjusted. In a normal development project the area in question is already in the possession of one owner or is acquired by one owner through purchase, expropriation or a similar process (Figure 1, cases 1, 2 and 4). The developer (public or private) will then (usually) produce a development plan (detailed plan) in co-operation with the municipality, and implement the project. However, placing the whole development area into the possession of one owner when there is a fragmented property and ownership structure is both expensive and time-consuming (case 4) and development projects are therefore often difficult to accomplish. For example, even though an area may appear well suited for development, this may not be the view of the owners and/or the community. Opinions on the course and timing of the development project may differ, as can the willingness of the various landowners to participate or take risks. There may even be a lack of resources to implement the project. The development of an area may thus be delayed for a considerable time. As a consequence, in a number of countries several types of legal instruments for urban land readjustment have been elaborated in order to ease such situations. (Figure 1, case 3). The urban land readjustment procedure can thus be considered either as a method for urban land development (by landowners) or as a tool for planning implementation (by society). Different countries have reached different solutions depending on, for example, the planning system already in existence and the attitude towards the responsibilities of the private and the public sectors in producing urban land. In practice, however, the differences seem less dramatic than one might think.

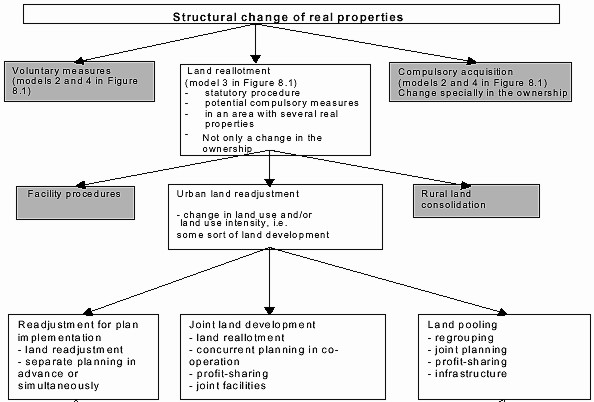

Figure 1 Four models to adapt the ownership and property structure to changes in land use (Kalbro 1992, Larsson 1991). A development process in connection with the urban land readjustment procedure does not differ from a "normal" land development process in the main stages, which, according to Kalbro, (1992) are: initiation, land acquisition, planning, financing, permission by the authorities, construction of the infrastructure and buildings, and evaluation of the project. Generally speaking, all of these stages can be implemented by the urban land readjustment procedure and a pool of landowners (readjustment association) instead of an individual developer will answer for the procedure. At the very least, the readjustment procedure can be regarded simply as a method for changing the division of land. In 1997 a new Real Property Formation Act came into force in Finland which redefined the urban land readjustment procedure. This act repealed the former urban land readjustment (kaavauusjako) procedure, which had been in force for 36 years, but had hardly ever been applied in practice (Viitanen 2000). In this article the focus is the new Finnish urban land readjustment (rakennusmaan järjestely) procedure, as defined by the new Act, and, in particular, its role in the development process, i.e. how the instrument works and how it could be improved. This article is based on a study done the author at the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden (Viitanen 2000). 2. CLASSIFICATION OF URBAN LAND READJUSTMENT PROCERUDESThe fundamentals of the urban land readjustment procedure are based on those rural land consolidation processes successfully carried out during the past centuries. The actual origins are considered to be in Germany, where urban land readjustment procedures were already practised in the late 19th century. Occasional readjustment procedures in town areas had, in fact, taken place centuries earlier, for example, after great fires. The urban land readjustment procedures can be classified and distinguished from the other proceedings relating to real property rights according to Figure 2. When an area is developed by changing the ownership structure (see also Figure 1) it is carried out either voluntarily or by compulsory means. As a result, the real property structure in the area will also usually change. Land reallotment can be classified between these voluntary and compulsory proceedings, as the ownership will mainly stay the same and only the property division will change. In addition to the urban land readjustment procedure, reallotment procedures are also used in rural areas (rural land consolidation). Reallotment can also be used only for changing the rights of use of the land, e.g. for facility procedures. Characteristic of the urban land readjustment procedure is a change in existing land use and/or land use intensity with the purpose of producing or reorganising built-up areas.

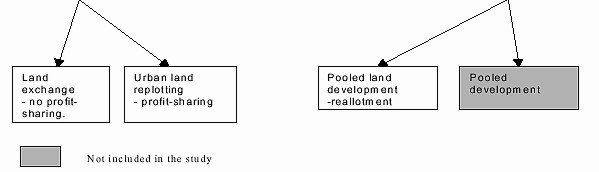

Figure 2 Classification of urban land readjustment procedures. The urban land readjustment procedures can be divided into three further categories: readjustment for plan implementation, joint land development, and land pooling. The procedure for readjustment for plan implementation is based on a detailed local plan prior to the procedure, and depending on whether or not the profit has been shared out between the landowners, we can talk either about urban land replotting on one hand or an exchange of land on the other. A feature of the joint land development procedure is that the detailed local plan is prepared in connection with the land readjustment process, but yet as a separate process in its own right (see Figure 3 alternative C). In the land pooling procedure landowners organise and implement the readjustment procedure with the related detailed land use plans in one and the same process (see Figure 3 alternative D). If the co-operation only involves the production of building land ready for construction, we can talk about pooled land development. If the construction of buildings is also included, it is pooled development. With the exception of pooled development, all other urban land readjustment procedures are included in this study. The procedures studied indicate that the German Umlegung can mainly be classified as urban land replotting or as joint land development, the Swedish exploateringssamverkan as joint land development, and the French AFU de remembrement as pooled land development. The Finnish urban land readjustment (rakennusmaan järjestely) can mainly be classified as urban land replotting, and the former urban land readjustment (kaavauusjako) as exchange of land. 3. URBAN LAND READJUSTMENT AND LAND USE PLANNINGThe urban land readjustment procedure is very closely linked to detailed local planning and other land use planning. In the countries studied, urban development is based on plans democratically approved while urban land readjustment procedure planning is carried out in a number of different ways (Figure 3). At its simplest, the urban land readjustment procedure only implements the existing plan without the processes themselves having any point in common. Planning and the urban land readjustment procedure can even be integrated into one process to obtain synergetic benefits, better participation, cost and time savings, and improved plans. This will, however, produce difficulties in the organisation of the functions and in the co-operation between the various processes. In practice, the extent of the readjusted areas varies from large - more than one hundred hectares - to small - less than one hectare. The areas may be unbuilt (areas of expectation value) or urban quarters to be redeveloped. In the readjustment process the pieces of land in an area are notionally assembled in one pot, where the joint owner has a share according to the acreage of the property owned by him in the readjustment area or according to the value of the land he owned before the procedure began. The areas will be replotted between the joint owners, so that each of them receives his share of the readjustment area and the real estate boundaries are adjusted according to the detailed plan. Public areas are usually transferred to the municipality, the rights relating to real properties are rearranged, necessary compensations are determined, and the infrastructure required for the area may also be implemented and the financing for its development obtained. The construction of the building sites is usually not included in the readjustment procedure. The costs for the readjustment procedure are covered either by the landowners or the municipality, or by both jointly. In order to cover costs, the municipality usually has the right to a share of the profit resulting from the readjustment procedure in the form of parcels of land.

Figure 3 Optional connections between planning and the urban land readjustment procedures (Viitanen 1995). 1) 1) By the various planning and land use agreements the plans and land readjustment procedures can be more closely connected than is represented by these basic principles The urban land readjustment procedure is justified not only on the basis of cost and efficiency but also on the basis of its fair treatment of landowners, improvements in plan quality, savings to the community, and environmental benefits. Under normal planning conditions the landowner may avail him/herself of the land value increment or decrement created by the plan depending on the intended use according to the plan, i.e. the value of the property may increase considerably or even decrease. In the readjustment procedure the land value changes can be fairly and equally divided between the landowners. The procedure will therefore also contribute to preventing speculations about planning. As the property boundaries can be disregarded when preparing the plan, the number of potential plan solutions will essentially be increased and finally the quality of the plan itself improved. At the same time the existing social structure can also be maintained (contrary to a situation where expropriation of the area is used). It has been noted, especially with smaller-scale developments, that the small entrepreneurs/owners are prepared to invest in the development of their area with little expectation of profit, only if they feel the unsatisfactory situation in their area will improve. The participation of landowners cannot therefore be directly measured in terms of money, but it seems that they must have at least some chance of obtaining a share of any future profits. When cities expand, construction and maintenance costs for the infrastructure increase considerably as does environmental damage. Implementation of the urban land readjustment procedure in areas within the existing urban structure or neighbouring unbuilt or under utilized areas will result in cost savings, reduce pollution and help to preserve the natural environment. In addition, as the procedure can also be implemented in areas that would otherwise be difficult to include despite their favourable urban structure and environment, further considerable cost savings can be achieved and environmental damage minimised. The urban land readjustment procedure is not, however, a trouble-free instrument. The processes needed are often very demanding and complicated and require those involved to display considerable expertise. The decision-makers should also be familiar with the operating mechanisms and options so that implementation of the procedure is not jeopardised through ignorance. Political, administrative and professional conflicts of interest can also come into play, sometimes resulting only in an ineffectual adoption of the procedure. However, because of its many positive benefits the urban land readjustment procedure has already survived for a century, and seems not to be under threat where its use is common. 4. THE FINNISH URBAN LAND READJUSTMENT PROCEDUREIn Finland the urban land readjustment procedure is legislated by the Real Property Formation Act (554/1995). It is provided for the proceedings that the procedure is allowed to be used only by the first detailed plan prepared for the area, i.e. it cannot be used in a situation where a detailed plan will be changed. The procedure is begun when an application from a landowner or a municipality is received at the National Land Surveying Office. The application has to be made before the detailed plan becomes legally binding. After the plan is approved cadastral surveyors determine if the legal provisions for the procedure are met and define the readjustment area. Their decision is publicly displayed and those objecting to it can appeal to the Land Court. After the decision is validated cadastral officers first confirm the basis for the apportionment in accordance with the real property values existing before the detailed local plan was prepared and then produce the readjustment plan. Public areas are partitioned and transferred to the municipality, and the municipality is required to compensate for those areas that exceed the free transfer obligation. The remaining areas (sites) are shared between the participants according to the participatory shares. Any differences are compensated. The parties have the right to agree on the form of compensation. Procedure costs are covered by both the municipality and landowners. Appeals against the final results of the procedure may be made to the Land Court. After validation, the readjustment is registered in the real property register and compensation is paid. The procedure does not include the construction of infrastructure. The strengths of the Finnish urban land readjustment procedure lie in its well-defined structure and organisation, but it also has its weaknesses. Although the aim of the procedure is to achieve better-detailed local plans, planners often do not know in practice if the readjustment procedure can be carried out, due to the extensive legal provisions. Therefore, the readjustment procedure may not, in fact, always function as a planning instrument. A further aim of the procedure is the equal treatment of landowners. However, if the readjusted area includes both built-up sites and unbuilt pieces of land (raw land), the procedure and the basis for apportionment results in the owners of the built-up properties acquiring the bulk of new sites. Under normal circumstances, this cannot be considered equitable. The right of minor owners to their own building sites, the apportionment of the unbuilt areas (e.g. agricultural land), the determination of certain compensations, and the procedure cost divisions may create further problems. Indeed, there is evidence that for the first three years during which the Real Property Formation Act has been operational not one single urban land readjustment procedure has taken place. This may be due in part to the fact that the procedure has not been incorporated into the Land Use Planning and Building Act, and thus planners have little experience of its potential benefits. It seems, therefore, that the existing regulations are ineffective in meeting the needs of urban land readjustment, and further improvements are urgently required. 5. GENERAL CONCLUSIONSThe study shows that for an effectual and vital urban land readjustment procedure some general requirements should be established:

The study revealed several weaknesses in the Finnish urban land readjustment procedure and the need for further development that will require amendments to the legislation. Failure to take such measures will place in jeopardy the future use of the procedure. In addition to these general requirements it is also essential to tackle the problems of the starting phase (pre-process) especially in connection with local planning, and also to develop the content and the structure of the proceedings themselves. By law, the urban land readjustment procedure has two goals: sharing out building rights and adapting the boundaries of properties to the sites designated in the detailed plan. The requirements and the structure of the proceedings, however, make it impossible to attain only one of these goals. Both of them must be implemented although this may not always be practical or realistic. Thus, the present rules may lead to a situation where the benefits of the procedure will be outweighed by needless costs and the consequence could be that the procedure will not be used. Changing the situation is not difficult, however, and regulations should therefore be developed to permit the attainment of only one of these goals. The urban land readjustment procedure, which ensures the fair treatment of landowners, is intended primarily as a planning instrument, in order that planners can produce better plans. However, many of the provisions of urban land readjustment are enshrined in law, which makes it impossible for planners to know whether or not the procedure can be implemented. Plans cannot normally be prepared without the planner taking into account the issue of fairness. In order to encourage its use, the urban land readjustment procedure should either begin by adhering to a local land use plan or the plan should be prepared conditionally, with validation only guaranteed if the procedure is carried out within a specified period of time. Initiating the procedure during the planning stage, especially in determining its implementation potential, may also establish a working solution, providing there is increased co-operation between the various authorities and that no substantial extra costs and delays are incurred during the development process. For example, the economic preconditions for implementing the procedure could be specified in advance: an unprofitable procedure should not actually be undertaken. The efficiency aspect should always be borne in mind. If there was better integration between the proceedings and the planning process (especially when aiming at sharing out building rights), the complicated prerequisites of the law could then be simplified. Voluntary agreement between parties about implementation or an alteration to the plan by the municipality before the readjustment procedure commences should be sufficient to prohibit the use of the procedure. Correspondingly, there should be better clarification and definition of the readjusted area on plan or during the planning process. The formal proceedings, which follow the decision to carry out the readjustment, also need further development, in particular the basis used for apportionment, the transference of sites, and the determination of compensation and costs. Under the existing laws, owners of built real estate receive a considerably larger share of the partitioned area compared with those who own unbuilt land with expectation value. This is because the basis of apportionment is dependent on the value of real properties and the fact that built properties are also given a participatory share. Although in practice, the statutes lead to unfairness in some cases, the law will not permit the matter to be settled otherwise, even though the participants may have reached a mutual agreement. In addition, when the value of a participating property is negative, for example, due to contamination, the value-based partition principles cannot be logically applied. The partition principles and/or the statutes on the inclusion of the built properties should therefore be reconsidered. An appropriate alternative would be an area-based apportionment principle with, if necessary, a grading value on development potential. Real properties, built in accordance with the detailed plan (and with granted building permits) would be included in the designation of building rights only if they brought developable land to the project (reference to the Swedish exploateringssamverkan proceedings). Further, the apportionment principle should not be seen as an absolute solution. It should be regarded primarily as a method for restoring fairness and should be flexibly handled to limit costs. The owners of small land areas are in an exceptionally favourable position in Finland: it would seem that every willing landowner is entitled to a building site as the number of sites appears to equal the number of participants. Although such a situation might often favour the social structure of the area, it will lessen the willingness of professional developers and large landowners to participate in the procedure, and thus reduce its effectiveness. It would therefore seem expedient to amend the law so that an individual's right to his share of a building site cannot be reduced by more than a specified amount (e.g. 20 %) without consent, except in situations where the share is insufficient even as one building site. Such a small share should be expropriated, as it is possible to do today, through rural land consolidation proceedings and compulsory purchase proceedings, in order to acquire a missing part of a plot in accordance with the detailed plan. The regulations concerning buildings and facilities seem ambiguous in respect of compensation, especially when it is the public sector that is responsible for making these payments. The regulations need to be clarified, so that regardless of the way in which any area is transferred to the public sector, the compensation laws for both buildings and facilities are neutral compared to the other (optional) proceedings. By altering the way in which compensation is allocated for areas initially transferred to the municipality, a better cash flow situation would be achieved if payments were made jointly to the participants to defray the costs they incur during implementation of the procedure. The privileged position of the municipalities as a result of the Real Property Formation Act should be surrendered as there can be no justification for its survival and nothing similar can be found in any of the other countries studied. Indeed, the current circumstances only tend to weaken the credibility of the municipality as a partner in the procedure. In order to improve the functionality and adaptability of the urban land readjustment procedure it should be composed of a number of elements, so that only the element required or a combination of elements would be used in any particular situation. The opportunities for the participants to make agreements on, for example, the measures to be taken and the methods of implementation, should obviously be increased. The urban land readjustment procedure might, for example, be composed of the following elements, and the first one would be the basis for those that followed: the provisions and the basic characteristics of the urban land readjustment procedure,

By amending the statutes and the proceedings the use of the urban land readjustment procedure might become a familiar activity when developing the urban structure in areas with fragmented ownership. REFERENCESKalbro, T., 1992, Markexploatering. Ekonomi, juridik, teknik och organisation. LMV-rapport 1992:4, 288 pages, Gävle, Lantmäteriverket. Larsson, G., 1991, Exploatering i samverkan. En jämförande internationell studie. Meddelande 4:65, 94 pages, Stockholm, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Institutionen för fastighetsteknik. Viitanen, K., 1995, Kiinteistöalan tulevaisuuden näkymistä. Kuntatekniikka - Kommunteknik 6:1995, pages 31-37. Viitanen, K., 2000, Plannyskifte - ett finskt omregleringsförfarande som inte användes? Meddelande 4:83, 54 pages, Stockholm, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Institutionen för fastigheter och byggande, Avd. Fastighetsvetenskap. Viitanen, K., 2000, Finsk reglering av byggnadsmark i ett internationellt perspektiv. Meddelande 4:84, 397 pages, Stockholm, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Institutionen för fastigheter och byggande, Avd. Fastighetsvetenskap. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTEKauko J Viitanen (born 1955), Professor of Real Estate Economics and Valuation, Ph.D. Professional career: CONTACTProfessor Kauko Viitanen, Ph.D. 21 April 2001 This page is maintained by the FIG Office. Last revised on 15-03-16. |